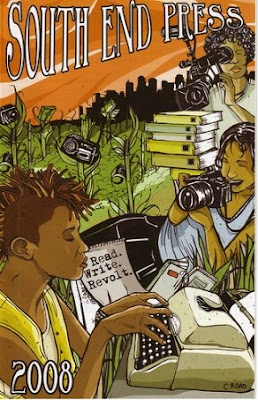

Ayuda South End Press!

I came across a post on my friend Maile's blog the maile vine, where she posted a request for support recently made by South End Press. I'm posting the entire request letter below for you to check out and learn more about their situation.

This year, the financial woes of Borders bookstores have hit South End Press especially hard. As a way to deal with its own troubles, Borders returned massive amounts of books. This means fewer copies of classics by South End authors like bell hooks, Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, and Vandana Shiva on the shelf for book browsers to happen upon. And as Borders returns came at the same time as end-of- semester returns it also means that for several months South End Press will receive no payments from our trade distributor–our main source of income. It hurts living paycheck to paycheck, especially when the checks don’t come.

Our worry about how to deal with the immediate cash crisis saps time that we would otherwise spend on publishing and promoting new books, and on trying to do our part in building a better world. For more than 30 years, we have found ways to carry on. We are committed to surviving this crisis, but we need your help to ensure that we can keep publishing new titles. The Right has strategically funded its own presses and media; the left must do the same.

This is why we’re inviting you to join the CSP Movement: we can’t afford to confuse independence with isolated individual efforts. South End has remained independent only because of the success of our community interdependence.

The ability of South End Press to sustain democratic movements advancing social and economic justice pivots on a community-based model. So does the fact that we manage our own labor collectively, that we work daily to invert the pernicious hierarchies of the publishing industry, that we try to create the change we hope to see in the broader world. So does the fact that we don’t answer to a corporate marketing and sales department, that while we too are struggling to survive in a capitalist system our mission remains the same: to publish books we believe in, books that bring critical, radical perspectives to bear on issues that matter. None of this would be possible without the support of an entire community of readers, activists, ruminators, and dreamers.

But community starts with people. With you. And with me. Consider this: it costs roughly $30,000 just to produce one new book, even with a lot of donated labor. That’s a big number for most of us, maybe even feels impossible to visualize. But that’s where the power of us, and Community Supported Publishing Movement, comes in: If you join the official CSP program, that’s building toward our goal of 1000 enrolled members by the end of the year. That means that we could produce at least 8 books like the recent groundbreaker The Revolution Will Not Be Funded. And if South End Press were no more, who would be willing to publish the next Exile and Pride: Queerness, Disability and Liberation; Ain’t I a Woman; or Outsiders Within: Writing on Transracial Adoption? Censorship takes many forms.

South End Press needs many $10, $25, $50, $100, and $500 contributions to put a new book into the world. We have finished manuscripts waiting to be produced, but we might not have the money to print and promote them. Please respond soon, as we are facing our worst times in the coming months. Your membership in the CSP movement will ensure that South End continues advancing our movements for social justice; not because there’s a market for it but because we demand it.

I hope you'll take some time, and some of your money (and or like me credit) and support them. Sen mangge este na inetnon. Gof impottante i che'chon-niha. Put fabot, ayuda siha. Yanggen gaikepble hao, fanmamahan lepblo siha.

South End Press is a very good press, and one I've dreamed about being published by for a long time (na'funhayan i eskuela-mu fine'nina!). As a grad student I often tell myself that I'm so strapped for money that I have to buy the cheapest crap in order to get by. But I'm slowly learning that it would be far better (even if it costs more) to invest my meager monies in important social justice/alternative projects such as South End.

So on the advice of Maile, I purchased a few books from South End, most notably the volume Islands in Captivity, which is drawn from testimony given at the 1993 Peoples' International Tribunal, which was organized primarily to commemorate the centennial of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, but also included evidence of other American crimes. I difunton Angel Leon Guerrero Santos was present at this event and provided testimony as to American colonialism in Guam. I've heard from others about his time there, but never actually read his statement. I'm really looking forward to getting my copy and finally checking it out.

Another book that I was very interested in and ended up purchasing is Manifestos on the Future of Food and Seed, edited by Vandana Shiva. As I prepare to move back to Guam for the next year, I am starting to pay more attention to the issues of sustainable agricultural and farming. An July 15th Pacific Daily News article titled "Farmers Face Difficulties," outlines how rising costs of supplies and the inconsistent market for fresh fruits and vegetables on Guam is making farming a more and more difficult vocation. The majority of Guam's fruits and vegetables are imported from off-island, and grocery vendors tend to only purchase local foods while waiting for off-island shipments to arrive. This preference for off-island goods makes it difficult to sustain a local farming economy.

My family has some small plots of land in Talo'fo'fo', and I'm determined to try and plant some small gardens there, as experiments or test runs, in hopes for eventually building a larger communal farming operation there.

When I was a young boy on Guam and my family lived in Talo'fo'fo' we had a small pineapple farm on this property. Depending on how much time I have on my hands (and with my dissertation still waiting to be written, probably not much), this might not be an option, but I would still like to eventually build something on the property. Before I was born, my great grandfather Tun Emo' (Kabesa) farmed on the land and on other parcels outside of the village. I have heard so many stories about my great grandfather and his love for the land, and so I would like to in someway carry on that tradition. I'm hoping that this book will give me some insight before moving forward with this.

When I was a young boy on Guam and my family lived in Talo'fo'fo' we had a small pineapple farm on this property. Depending on how much time I have on my hands (and with my dissertation still waiting to be written, probably not much), this might not be an option, but I would still like to eventually build something on the property. Before I was born, my great grandfather Tun Emo' (Kabesa) farmed on the land and on other parcels outside of the village. I have heard so many stories about my great grandfather and his love for the land, and so I would like to in someway carry on that tradition. I'm hoping that this book will give me some insight before moving forward with this.I also purchased When the Prisoners Ran Walpole, just out of curiousity. My male' Nicole Santos gave me several years ago, a copy of Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Davis. Prior to reading that book I hadn't heard about the prison abolitionist movement, and never really considered that there were alternatives to the modern system of punishment and incarceration. Every once in a while I enjoy reading up on this, and so this book sounded very interesting in that regard.

One other reason that I'm supporting South End Press is a selfish and self-serving one. I have a chapter in a book that they will hopefully publish sometime in the next year. In 2004 I was fortuante enough to be invited to attend and present at the Sovereignty Matters conference at Columbia University. Later, my paper "Everything You Wanted to Know About Guam, But Were Afraid to Ask Zizek" was accepted to be published in a volume comprised of papers presented at the conference, titled Sovereign Acts.

According to the editor Frances Negron Muntaner, who was also the main organizer for the 2004 conference, the volume was supposed to be published this August, but it doesn't look like that will happen. I'm really hoping it does get published soon, since it will be an important companion to an existing text which was derived from a conference with the exact same name. Last year the volume Sovereignty Matters: Location of Contestation and Possibility in Indigenous Struggles for Self-Determination was published. It featured for those concerned with Guam and Chamorro issues, an article by Chamorro sociologist Michael Perez titled "Chamorro Resistance and Prospects for Sovereignty in Guam." The piece is a good history of the recent anti-colonial movements that have taken place on Guam, especially at the international level, meaning dealing with the United Nations.

I think that my piece in the Sovereign Acts volume will be a good addition to that historical discussion the piece starts. My paper is much more theoretical and relocates sovereignty in different spheres, away from the more abstract, mainstream versions. I've pasted below, an excerpt from the article:

*************************

Very few people know this but we are currently living in the 2nd decade of United Nation’s efforts to officially eradicate colonialism.[1] While colonialism is something which is often invoked as a metaphor, a faded, worn and dirty, dirty lens through which the world today is politicized, implying that either something which was banished has returned and must be sent back to the abyss, or that it has evolved into a more hybrid, and dangerous creature, it is important to remember that it still exists.[2]

Those who seek to articulate oppression or injustice use “colonization” to make clear the inequality of a relationship, the extension of such violence and exploitation to a structural level, and also draw a clear genealogical connection to the brutal imagery of previous ages of domination.[3] On the other end of the spectrum, we find the assertion of a Tony Blair aide in 2003, that precisely what the world needs now, is colonialism.[4] The decolonized and developing world is failing to meet the promise of the international fraternity it was allowed to join, and so for those seeking to wield the sword of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Empire, they are infected with a hearty longing for colonialism.[5]

Those who seek to articulate oppression or injustice use “colonization” to make clear the inequality of a relationship, the extension of such violence and exploitation to a structural level, and also draw a clear genealogical connection to the brutal imagery of previous ages of domination.[3] On the other end of the spectrum, we find the assertion of a Tony Blair aide in 2003, that precisely what the world needs now, is colonialism.[4] The decolonized and developing world is failing to meet the promise of the international fraternity it was allowed to join, and so for those seeking to wield the sword of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Empire, they are infected with a hearty longing for colonialism.[5]For those then who continue to swim in colonialism proper, which is a group comprised primarily of small island non-nations, such as Guam, American Samoa and Puerto Rico, their lot is an comfortable, curious and yet maddening one all at once. In a world which has “gotten over” colonialism, but where the “failures” of decolonization seem to create epidemics of imperialistic nostalgia amongst both the formerly colonizer and colonized, ambiguous political status of Guam has been called by Guam scholar Robert Underwood, a comfortable one, but as Guam nonetheless floats atop a sea of banal political inclusions and exclusions, colonial nonetheless.[6] If we were to redefine colonialism to match the nature of a colony such as Guam today, we would quickly abandon discussions marked by terms such as oppression and subjugation and instead trot out terms such as, patriotism, liberation, dependency, banality, ambiguity and strategic military necessity. People on Guam are eligible for some Federal programs like welfare and food stamps, but are not able to vote for President. They can join the United States military, travel freely with a United States passport, and are US citizens whose political protections and rights are not derived from the United States Constitution, but an act of Congress. They do not pay Federal income taxes, and instead of full Senators or Representatives, receive a single non-voting Delegate to the United States Congress.

This ambiguity however isn’t duplicated in strategic military terms, as Guam is clearly one of the most crucial global sites for the projection of American military power, and has been since it was first taken in 1898. Listed by Foreign Policy magazine as one of the six most important US bases in the world, and often referred to by military commanders as things like the “tip of America’s spear” or “an unsinkable aircraft carrier” Guam has been crucial in conflicts from World War II, Korea, Vietnam in securing American economic and strategic interests throughout the Pacific and Asia.[7] At present in light of recent defense compact renegotiations in Asia, Guam is poised to receive the military presence which will be transferred out of bases in South Korea and Japan.[8] By 2014, the estimated total population increase to Guam, combining military personnel, dependents and support staff, will be 55,000, accompanied by a barrage of bombers, unmanned surveillance vehicles, Stryker tanks, and nuclear submarines.[9] The current population of Guam is only 168,000, and 1/3 of its 212 square miles is already controlled by the United States military.

HUGUA – between two deadlocks…

As I Chamorro from Guam, I see my island and its indigenous people trapped in a ghostly place, wedged between two menacing deadlocks. The first is referred to by Slavoj Zizek as “the liberal democratic deadlock,” the second I have often referred to in my work as the decolonial deadlock.”[10] Both of these deadlock insist that no other arrangement of the social or political order is possible or advisable, and therefore in the fear of the world, the island or society regressing into a previous evolutionary form, resist any and all radical or fundamental change.

HUGUA – between two deadlocks…

As I Chamorro from Guam, I see my island and its indigenous people trapped in a ghostly place, wedged between two menacing deadlocks. The first is referred to by Slavoj Zizek as “the liberal democratic deadlock,” the second I have often referred to in my work as the decolonial deadlock.”[10] Both of these deadlock insist that no other arrangement of the social or political order is possible or advisable, and therefore in the fear of the world, the island or society regressing into a previous evolutionary form, resist any and all radical or fundamental change.

For the liberal democratic deadlock, we find it best exemplified through the amateurish Hegelian reading of Francis Fukuyama which led him to proclaim the world had reached “the end of History.” [11] The Cold War for Fukuyama represented the last moment of “History” where equal opposites or even comparable antagonists faced off to decide the fate of the world or its course. With the United States the victor, the form of government and society it represents has won as well, there will be no more real changes in the world order, a victor has been declared, and all will either bend and assimilate to its will, or will be broken or obliterated.[12]

The decolonial deadlock is an overall resistance or reticence in Guam today, towards any need or even discussion of Guam’s decolonization. It is an either passive or active hegemonic formation, which circles around the idea that the best possible political and social configuration in Guam has been reached through its colonial relationship to the United States and nothing more need be done. The sort of sinthome or discursive mantra that props up this miasma, is the idea that the Chamorro is impossible, and can only exist as a loyal and dependent appendage of the United States. For Chamorros who accept this premise for life, then there is nothing more horrifying, to be forcefully resisted than decolonization, because of the threat it poses in weakening the influence and interests of the United States in Guam.

In this essay I am interested in exploring this ghostly place of Guam moving from democracy, to leprosy, to family, to tano’, and lastly to resistance, paying particular attention along the way to issues of culture and sovereignty.[13] In terms of culture I want to address both the colonizing and decolonizing realities and potentialities in Chamorro culture. The way it can on one hand constrict and constrain Chamorros by becoming a marker of their pathology and their corrupting influence which inevitably taints the “happy ending” the liberal democratic deadlock promises Guam. In another way however, culture is a political and mobilizing force, especially in the way it cannot help but embody, in passive or active conflict with the stories of necessary American greatness in Guam, an alternative vision, narrative or understanding of the world. My ultimate intent in this essay is to articulate Chamorro culture in Guam as a necessary catalyst for decolonization or assertions/expressions of Chamorro sovereignty, and the means through which the decolonial deadlock there might be broken.

**********************

[1] The United Nations, Press Release Reference Paper No. 44, 2 July 2005.

[2] The term “coloniality” has been created in order to address the ways in which imperialist and colonial power remains, despite the spectacle of transferred sovereignty, which characterized the “decolonizing” of the majority of the world’s population over the past century. As I will explain in slightly more detail later in this paper, there is something important and critically useful about maintaining a distinction between those who are still entangled in “colonialism” and those who were in different ways pushed or allowed into “coloniality.” Walter Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges and Border Thinking, (Princeton, Pinceton, 2000).

[3] This was made clear to me recently during a conversation with one of my friends about a proposal she was submitting for the 2007 US Social Forum regarding Guam and its status as a colony of the United States. While putting her proposal together, she had come across an existing proposal for the forum titled “U.S. Colonialisms.” She contacted the organizer to see what the content of their presentations would be and if it would be possible to join them. Interestingly enough, none of the communities covered by this panel were from the current “colonies” of the United States, but were instead US minority communities which were using the metaphor of “colonialism” to articulate their victimization. After suggesting that Guam would be an important addition to this panel, my friend was rebuffed through the curious argument that “Look, Puerto Rico is a colony, and we haven’t asked Puerto Ricans to be a part of this. Why should we ask Guam?” Tiffany Lacsado, Telephone Communication, 12 May 2007.

[4] Robert Cooper, “The post-modern state,” The Observer, 7 April 2002. Daniel Vernet, “Postmodern Imperialism” Le Monde, 24 April 2003.

[5] Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University, 2001).

[6] Robert Underwood, The Status of Having No Status. Speech presented at the annual College of Arts and Sciences Research Conference. University of Guam, Mangilao, Guam, April 26, 1999.

[7] Daniel Widome, “The List: The Six Most Important U.S. Military Bases,” Foreign Policy, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=3460, May 2006. Christian Caryl, “America’s Unsinkable Fleet: Why the US Military is Pouring Forces into a Remote West Pacific Island,” Newsweek International, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17202830/site/newsweek/ 26 February 2007.

[8] Gene Park, “7,000 Marines, Pentagon announces shift to Guam,” The Pacific Daily News, 30 October 2005. Clint Ridgell, “What to do with 8,000 Marines?” KUAM, http://www.kuam.com/news/17674.aspx, 2 May 2006.

[9] Elenoa Baselala, “Marines Relocation Angers the Indigenous: They Say It Could Mean the End of Their Race,” Island Business, May 2007.

[10] Slavoj Zizek, Iraq: The Borrowed Kettle, (London, Verso, 2004). Michael Lujan Bevacqua, Everything You Wanted to Know About Guam But Were Afraid to Ask Zizek, (M.A. Thesis, University of California, San Diego, 2007).

[11] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, (New York, Free Press, 1992).

[12] Slavoj Zizek, Welcome to the Desert of the Real, (London, Verso, 2003).

[13] Tano’: The Chamorro word for land.

Comments