The Spear can only be Broken by the Wound that Caused It

Ever since my manner, my writing and my work has become super theoretical one issue has persistently dogged me wherever I go. It pops up during my hysterical internal monologues over sections of my thesis ("oh crap, did I just accidentally reify the split I was trying to pass through?"), questions from Chamorros and others in response to my zany blog posts ("what the hell does "patriotic blowback" mean?") and from people who find my notion of being an "indigenous Lacanian" disturbing. What exactly is this issue, this question that haunts me?

Where does my critique emerge from in relation to modernity?

Okay, so maybe in that form it doesn't sound like something alot of people would ask on an everyday basis, but nonetheless it is this kernal that is always confronting me in my work, and by work I mean academically or what I produce explicitly for academics as well as intellectual work I do for anyone else anywhere.

The phrase "relation to modernity" is the key here, because basically when I critique the United States, when I articulate what decolonization means to me, and what it should be for others, from where am I positioning myself in relation to the thing that I am decolonizing or the framework I am critiquing? Do I place myself outside of modernity, do I root my articulation in something outside of it, or before it? Or do I position myself inside of modernity, making a critique and seeking to dissolve it from within?

I am an indigenous subject/non-subject, I am put into that position and I occupy it and chose to continue to occupy it. Yet, given the obvious friendliness of my work with "non-indigenous" theories and scholarship (Zizek, Lacan, Weezer, Evangelion, Pikachu) doesn't this affinity provide an easy autocritique of what I do? To put it another way, am I just reproducing, through my critiques of the ways Chamorros are representing themselves and their culture, the very thing I am attempting to critique, namely the impossibility of the Chamorro?

Depending upon what day of the week it is, my critical relationship to modernity changes, and regularly shows up in the different ways I relate to “indigeneity.” How I articulate it, how I occupy it, and how I resist it (my paper earlier this year on Whale Rider a perfect example). Some days I refuse to give European modernity that much credit, and I insist on the existence of something else, whether in the forms of alternative modernities or alternate epistemologies. Only through attempts to embody and inhabit these forms will real critiques of modernity take place. I work hard to articulate a Chamorro in defiance of the anthropological monopoly on it, which continues to colonize through the very concepts and tendencies that have yet to be decolonized and dealt with in very real ways. (for example, the dilemmia of indigenous peoples is that we are stuck with and stuck in culture, and the predicament of culture is that it is supposed to be stuck, static, and therefore indigenous peoples when entering modernity and modern representation are basically trapped within frameworks of oppressive and colonizing authenticity. In order to be visible to be audible we have to work to retain that cultural position, but speech, representation, like the vision of the T-Rex in Jurassic Park are all predicated on movement, a change, that which culture as it is dominantly articulated, not supposed to do). Some very vibrant recent examples that I've found of this strategy are coming from indigenous epsitemologies in Latin America, the Carribean and the Pacific.

Lately however, my days have not tend to be of the above type. While the hope for something different, outside of modernity remains with me and always makes cameo appearances, my theoretical push most often follows the logic of Slavoj Zizek and his critique of modernity, which provides an interesting way of giving it too much credit to it and giving it not enough credit at the same time. For him the logic of critiquing modernity lies in a line from Richard Wagner’s Parsifal, “Die Wunde schilesst der Speer nur, der si schlug,” “The wound can only be healed by the spear which made it." Or to echo the sentiments of Indian philosopher J.L. Mehta, when confronted with European modernity, “there is not other way open” save to pass through it." This meaning that modernity in its very production, in differing ways, provides the very means for its dissolution. To seek something outside of modernity, or more importantly for issues of indigeneity, something before it, is the most obvious way of ensnaring yourself in it.

Interestingly enough, in my paper Everything you Wanted to Know About Guam, but were Afraid to Ask Zizek: Part 1, I provided a different reading of his "spear" and "wound" spiel.

"The wound can only be healed by the spear that caused it," is therefore like the advice of a doctor, who’s advice is that what the patient needs is a good doctor’s advice, this wound comes with its own logic and its own trap. Colonizing impulses dictate that once wounded, it is the colonizer that Chamorros are to turn to, and to insist bitterly or wait patiently to be given access to that which has hurt them. To me, this is the response that leaves the wound misrecognized, unattended, festering in mythology, eventually becoming something akin to the grotesque thing from Franz Kafka’s story, “A Country Doctor." It becomes a sore so huge and gaping it begins to take a life on a life of its own, precisely because of the lack of understanding as to its purpose or source.

Pre-war and immediate postwar activism in Guam was marked by an obsession with finding the weapon that caused the wound. It can be summed up perfectly by the statements of former Speaker of Guam’s Congress, Carlos Taitano. While the United States Navy was snatching up ¾ of the island and Chamorros were complaining to members of the Guam Congress about what they felt was unfair treatment by Naval officials, Taitano’s response was basically what can we expect but this, “we are outside of the family now, how can we ask for anything when we are outside of the family?" To paraphrase this assimilationist logic, “we still have yet to find the weapon which has wronged us, what can we expect other than this?”

In response however, we have the horrifying insight of Deleuze and Guattari's Capitalism and Schizophrenia, where the almost divine power of capitalism (and I would argue modernity as well) is its ability to deterritorialize and reterritorialize, so that any old division or new division can be potentially constitutive of is power. The discussions of culture and its potential for resistance (Subcommandante Marcos, Amilcar Cabral, Franz Fanon) can easily be rendered moot, as capitalism has a way of sometimes savagely sometimes politely subsuming, engulfing and momentarily neutralizing at one time potentially threatening local traditions. Take for example the difference between the East India Company in Mangal Pandey's time with McDonald's today. By making mutton burgers McDonalds, through this respect for local traditions quickly becomes a member of the family. We have a similar issue on Guam, as Kentucky Fried Chicken has very much become a member of the Chamorro family by making hineksa' aga'ga and kelaguan wraps a part of their everyday menu.

The issue in my movement between these two positions, is not to actually pick one, because such a choice can never be sustained for very long. For some reason I've been quoting Ernesto Laclau alot lately, maybe its because if my grandfather was a Argentinean political theorist, he would be just like Laclau. Very grandfatherly and very formal, but very afraid to intellectual slap someone around. But, here is yet another quote from Laclau, this time from his punk-ass article "Can Immanence Explain Social Struggles?" from Empire's New Clothes: Reading Hardt and Negri.

"Here we find the real theoretical watershed in contemporary discussions: either we assert the possibility of a universality that is not politically constructed and mediated or we assert that all universality is precarious and depends on historical construction out of heterogeneous elements."

Ah yes, it sounds simple, but the truth is the sentence not the choice, as the choice is false, impossible. One cannot actually occupy this distinction, because although every universal can be shown to be contingent or insufficient in some way, the universal nonetheless always appears in the form of not a universal, but the universal. Isn't this the terribly annoying glitch of "postmodern" politics? That game that Bush and other conservatives are able to play so well? Is not the assertion of respect for a multiplicity of truths and differences, one of the best ways to protect the universality of a particular hegemonic truth? Aren't free speech zones one of the most profound recent examples of this?

What we are forced to always do then is articulate our position in relationship to this continually obvious and present, yet simulteanously and paradoxicaly ghostly movement. (is this one reason why "strategic essentialism" as a basic concept has to be renounced and disavowed? Not just because it provides a more defensible way of reinventing identity politics, but more so because it forces us to confront that identity will always be an element of politics (at present), and cannot be something that can be merely dismissed as divisive or counterproductive (as so many theorists have done and continue to do).

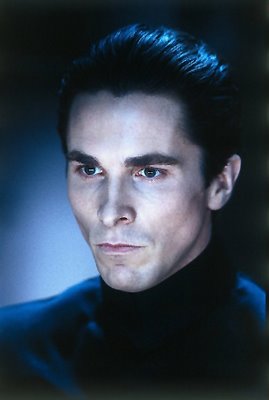

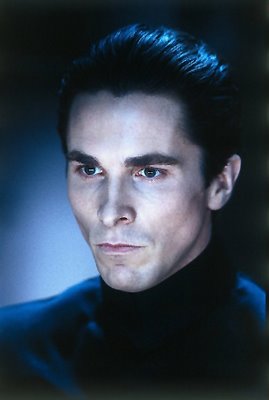

Earlier today while running errands, I accidentally ended up watching the film Ultraviolet. It along with its obvious inspiration Equilibrium (William Fichtner in pretty much the same role, as a broken white liberal, touchy feely guy who is way over his head in a world that has gone fascist all around him, I'm also pretty sure they are written by the same guy, Kurt Wimmer) clearly represent second critical logic I discussed, where a system can only be dissolved from within.

As we saw clearly in Matrix Reloaded, there is no system that does not have some sort of remainder (Neo). Therefore no system is ever completely closed or safe, but must continually work to create means to deal with these excesses. In The Matrix Trilogy we see a very elaborate system created to deal with the excess that Neo and more importantly the production of his position represent. But ultimately even this new regime cannot contain that excess, and leads to potential new threats (take for example Ray Liotta in No Escape).

In Ultraviolet and Equilibrium we see the application of power, or violence to deal with a threat leading to the creation of something which that power cannot contain. The creation of something which can potentially outviolence its source (The Saint of Killers in Preacher).

In its quest to create more powerful soldiers, a genetic mutation is created which begins to afflict certain members of the human race. The "government" acts to contain this new threat, to destroy it, thus creating in different ways Violet or V, who naturally at the film's end, destroys those that produced her.

In Equilibrium, a world without passion or emotion is also one of everlasting "peace." This peace however is kept by schizoid state inducing drugs and brutal soldiers and clerics who diligently destroy all potentially stimulating material, such as art, books, poetry, music. John Preston is one such grammaton cleric who at the film's beginning effortlessly wipes out entire rooms of "sense offenders." Through the course of the film however, he begins Preston begins to feel and eventually fights to overthrow the government for which he blindly killed on behalf of.

In Equilibrium, the resistence, those who resist from "the outside" those who could be classified under the logic of the first critique are easily massacred and destroyed by the State. Their fight is always a losing battle, it is only when one from within, Preston joins them that their battle is successful, and a revolution lead by Preston's destruction of the State's leader takes place.

The discussion of these two films of course leads me to discuss another film in the dystopia bad ass genre, the soon to be released V for Vendetta.

V for Vendetta is slightly different from the other two because of the way that V, the agent of revolution, remains basically an enigma. His origin is not revealed as Violet's was, as a normal human woman, until she became infected with the blood virus and later lost her child to the State's experiments on her.

The camp from where we first meet V, Code Name V, the man from room Five or V, is an incredibly heterogenous space, it is full of all the not white people in Britian that survived a nuclear holocaust, as well as all the homosexuals, intellectuals, insane people and artists. Our only concrete knowledge of him is that he was wronged and he seeks retribution and vengeance (but is it for himself, for the woman he loved in the room next door, for whom?), but his face is never revealed, his identity never given to us in such a way that we could situate from where his power comes from. (the movie in a way diminshes this, by giving him amnesia and creating a clear lack of history for V).

For example, is his intelligence, his strength, his madness a result of the experiments that they conducted on him and others? Or was it something already there, prior to the camp, prior to everything? Because we never see his face, and I mean this both in literal terms (we are stopped just before Evey is about to reveal it, because of the realization that his face doesn't matter, only the position he mometarily occupies, and holds for someone else) as well as ontological terms. The source of this drive, is it something created through the exploitation and oppression of the system that is built following the nuclear holocaust? Or is it something that existed even prior to that destruction? Something that this system can't only not account for, but can't take credit for.

Where does my critique emerge from in relation to modernity?

Okay, so maybe in that form it doesn't sound like something alot of people would ask on an everyday basis, but nonetheless it is this kernal that is always confronting me in my work, and by work I mean academically or what I produce explicitly for academics as well as intellectual work I do for anyone else anywhere.

The phrase "relation to modernity" is the key here, because basically when I critique the United States, when I articulate what decolonization means to me, and what it should be for others, from where am I positioning myself in relation to the thing that I am decolonizing or the framework I am critiquing? Do I place myself outside of modernity, do I root my articulation in something outside of it, or before it? Or do I position myself inside of modernity, making a critique and seeking to dissolve it from within?

I am an indigenous subject/non-subject, I am put into that position and I occupy it and chose to continue to occupy it. Yet, given the obvious friendliness of my work with "non-indigenous" theories and scholarship (Zizek, Lacan, Weezer, Evangelion, Pikachu) doesn't this affinity provide an easy autocritique of what I do? To put it another way, am I just reproducing, through my critiques of the ways Chamorros are representing themselves and their culture, the very thing I am attempting to critique, namely the impossibility of the Chamorro?

Depending upon what day of the week it is, my critical relationship to modernity changes, and regularly shows up in the different ways I relate to “indigeneity.” How I articulate it, how I occupy it, and how I resist it (my paper earlier this year on Whale Rider a perfect example). Some days I refuse to give European modernity that much credit, and I insist on the existence of something else, whether in the forms of alternative modernities or alternate epistemologies. Only through attempts to embody and inhabit these forms will real critiques of modernity take place. I work hard to articulate a Chamorro in defiance of the anthropological monopoly on it, which continues to colonize through the very concepts and tendencies that have yet to be decolonized and dealt with in very real ways. (for example, the dilemmia of indigenous peoples is that we are stuck with and stuck in culture, and the predicament of culture is that it is supposed to be stuck, static, and therefore indigenous peoples when entering modernity and modern representation are basically trapped within frameworks of oppressive and colonizing authenticity. In order to be visible to be audible we have to work to retain that cultural position, but speech, representation, like the vision of the T-Rex in Jurassic Park are all predicated on movement, a change, that which culture as it is dominantly articulated, not supposed to do). Some very vibrant recent examples that I've found of this strategy are coming from indigenous epsitemologies in Latin America, the Carribean and the Pacific.

Lately however, my days have not tend to be of the above type. While the hope for something different, outside of modernity remains with me and always makes cameo appearances, my theoretical push most often follows the logic of Slavoj Zizek and his critique of modernity, which provides an interesting way of giving it too much credit to it and giving it not enough credit at the same time. For him the logic of critiquing modernity lies in a line from Richard Wagner’s Parsifal, “Die Wunde schilesst der Speer nur, der si schlug,” “The wound can only be healed by the spear which made it." Or to echo the sentiments of Indian philosopher J.L. Mehta, when confronted with European modernity, “there is not other way open” save to pass through it." This meaning that modernity in its very production, in differing ways, provides the very means for its dissolution. To seek something outside of modernity, or more importantly for issues of indigeneity, something before it, is the most obvious way of ensnaring yourself in it.

Interestingly enough, in my paper Everything you Wanted to Know About Guam, but were Afraid to Ask Zizek: Part 1, I provided a different reading of his "spear" and "wound" spiel.

"The wound can only be healed by the spear that caused it," is therefore like the advice of a doctor, who’s advice is that what the patient needs is a good doctor’s advice, this wound comes with its own logic and its own trap. Colonizing impulses dictate that once wounded, it is the colonizer that Chamorros are to turn to, and to insist bitterly or wait patiently to be given access to that which has hurt them. To me, this is the response that leaves the wound misrecognized, unattended, festering in mythology, eventually becoming something akin to the grotesque thing from Franz Kafka’s story, “A Country Doctor." It becomes a sore so huge and gaping it begins to take a life on a life of its own, precisely because of the lack of understanding as to its purpose or source.

Pre-war and immediate postwar activism in Guam was marked by an obsession with finding the weapon that caused the wound. It can be summed up perfectly by the statements of former Speaker of Guam’s Congress, Carlos Taitano. While the United States Navy was snatching up ¾ of the island and Chamorros were complaining to members of the Guam Congress about what they felt was unfair treatment by Naval officials, Taitano’s response was basically what can we expect but this, “we are outside of the family now, how can we ask for anything when we are outside of the family?" To paraphrase this assimilationist logic, “we still have yet to find the weapon which has wronged us, what can we expect other than this?”

In response however, we have the horrifying insight of Deleuze and Guattari's Capitalism and Schizophrenia, where the almost divine power of capitalism (and I would argue modernity as well) is its ability to deterritorialize and reterritorialize, so that any old division or new division can be potentially constitutive of is power. The discussions of culture and its potential for resistance (Subcommandante Marcos, Amilcar Cabral, Franz Fanon) can easily be rendered moot, as capitalism has a way of sometimes savagely sometimes politely subsuming, engulfing and momentarily neutralizing at one time potentially threatening local traditions. Take for example the difference between the East India Company in Mangal Pandey's time with McDonald's today. By making mutton burgers McDonalds, through this respect for local traditions quickly becomes a member of the family. We have a similar issue on Guam, as Kentucky Fried Chicken has very much become a member of the Chamorro family by making hineksa' aga'ga and kelaguan wraps a part of their everyday menu.

The issue in my movement between these two positions, is not to actually pick one, because such a choice can never be sustained for very long. For some reason I've been quoting Ernesto Laclau alot lately, maybe its because if my grandfather was a Argentinean political theorist, he would be just like Laclau. Very grandfatherly and very formal, but very afraid to intellectual slap someone around. But, here is yet another quote from Laclau, this time from his punk-ass article "Can Immanence Explain Social Struggles?" from Empire's New Clothes: Reading Hardt and Negri.

"Here we find the real theoretical watershed in contemporary discussions: either we assert the possibility of a universality that is not politically constructed and mediated or we assert that all universality is precarious and depends on historical construction out of heterogeneous elements."

Ah yes, it sounds simple, but the truth is the sentence not the choice, as the choice is false, impossible. One cannot actually occupy this distinction, because although every universal can be shown to be contingent or insufficient in some way, the universal nonetheless always appears in the form of not a universal, but the universal. Isn't this the terribly annoying glitch of "postmodern" politics? That game that Bush and other conservatives are able to play so well? Is not the assertion of respect for a multiplicity of truths and differences, one of the best ways to protect the universality of a particular hegemonic truth? Aren't free speech zones one of the most profound recent examples of this?

What we are forced to always do then is articulate our position in relationship to this continually obvious and present, yet simulteanously and paradoxicaly ghostly movement. (is this one reason why "strategic essentialism" as a basic concept has to be renounced and disavowed? Not just because it provides a more defensible way of reinventing identity politics, but more so because it forces us to confront that identity will always be an element of politics (at present), and cannot be something that can be merely dismissed as divisive or counterproductive (as so many theorists have done and continue to do).

Earlier today while running errands, I accidentally ended up watching the film Ultraviolet. It along with its obvious inspiration Equilibrium (William Fichtner in pretty much the same role, as a broken white liberal, touchy feely guy who is way over his head in a world that has gone fascist all around him, I'm also pretty sure they are written by the same guy, Kurt Wimmer) clearly represent second critical logic I discussed, where a system can only be dissolved from within.

As we saw clearly in Matrix Reloaded, there is no system that does not have some sort of remainder (Neo). Therefore no system is ever completely closed or safe, but must continually work to create means to deal with these excesses. In The Matrix Trilogy we see a very elaborate system created to deal with the excess that Neo and more importantly the production of his position represent. But ultimately even this new regime cannot contain that excess, and leads to potential new threats (take for example Ray Liotta in No Escape).

In Ultraviolet and Equilibrium we see the application of power, or violence to deal with a threat leading to the creation of something which that power cannot contain. The creation of something which can potentially outviolence its source (The Saint of Killers in Preacher).

In its quest to create more powerful soldiers, a genetic mutation is created which begins to afflict certain members of the human race. The "government" acts to contain this new threat, to destroy it, thus creating in different ways Violet or V, who naturally at the film's end, destroys those that produced her.

In Equilibrium, a world without passion or emotion is also one of everlasting "peace." This peace however is kept by schizoid state inducing drugs and brutal soldiers and clerics who diligently destroy all potentially stimulating material, such as art, books, poetry, music. John Preston is one such grammaton cleric who at the film's beginning effortlessly wipes out entire rooms of "sense offenders." Through the course of the film however, he begins Preston begins to feel and eventually fights to overthrow the government for which he blindly killed on behalf of.

In Equilibrium, the resistence, those who resist from "the outside" those who could be classified under the logic of the first critique are easily massacred and destroyed by the State. Their fight is always a losing battle, it is only when one from within, Preston joins them that their battle is successful, and a revolution lead by Preston's destruction of the State's leader takes place.

The discussion of these two films of course leads me to discuss another film in the dystopia bad ass genre, the soon to be released V for Vendetta.

V for Vendetta is slightly different from the other two because of the way that V, the agent of revolution, remains basically an enigma. His origin is not revealed as Violet's was, as a normal human woman, until she became infected with the blood virus and later lost her child to the State's experiments on her.

The camp from where we first meet V, Code Name V, the man from room Five or V, is an incredibly heterogenous space, it is full of all the not white people in Britian that survived a nuclear holocaust, as well as all the homosexuals, intellectuals, insane people and artists. Our only concrete knowledge of him is that he was wronged and he seeks retribution and vengeance (but is it for himself, for the woman he loved in the room next door, for whom?), but his face is never revealed, his identity never given to us in such a way that we could situate from where his power comes from. (the movie in a way diminshes this, by giving him amnesia and creating a clear lack of history for V).

For example, is his intelligence, his strength, his madness a result of the experiments that they conducted on him and others? Or was it something already there, prior to the camp, prior to everything? Because we never see his face, and I mean this both in literal terms (we are stopped just before Evey is about to reveal it, because of the realization that his face doesn't matter, only the position he mometarily occupies, and holds for someone else) as well as ontological terms. The source of this drive, is it something created through the exploitation and oppression of the system that is built following the nuclear holocaust? Or is it something that existed even prior to that destruction? Something that this system can't only not account for, but can't take credit for.

Comments