We Are War Stories

I gave a lecture recently at University of California, Riverside, on Chamorro soldiers, and the relationship between colonization and militarization in Guam. I gave it just a few days after I had returned to San Diego from a brief visit in Guam for Sumahi's first birthday.

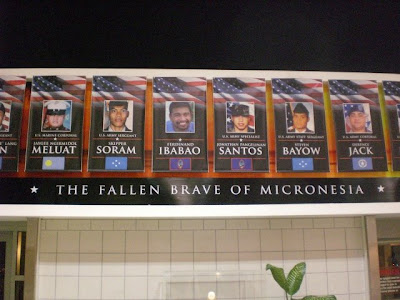

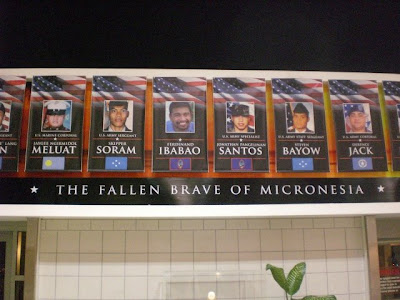

While I was at the airport waiting for my plane to board, I saw this homage, downstairs from the security screening area. It is an homage to all the soldiers that have died from Micronesia in Iraq, Afghanistan and Africa, in this always growing and expanding War on Terror.

Ni' ngai'an na bei maleffa i sinangan as Borat, annai ilek-na "War of Terror."

Ni' ngai'an na bei maleffa i sinangan as Borat, annai ilek-na "War of Terror."

When I share stories in the states, of America's colonization of Guam, and mix in both the bad with the good that it has brought to the island, people often then question me about why then, do Chamorros serve? Why do they choose to fight for a country which is and isn't theirs? A country which has done just as much good for them as bad?

When I share stories in the states, of America's colonization of Guam, and mix in both the bad with the good that it has brought to the island, people often then question me about why then, do Chamorros serve? Why do they choose to fight for a country which is and isn't theirs? A country which has done just as much good for them as bad?

All of the different territories, for very different historical and contemporary reasons could have different answers. Each could claim to have some similar experiences in their colonial or neocolonial relationship to the United States, but there are still very stark differences. But given their exceptional positions today, their is still plenty of room for questions as to why people in these islands would be so willing to sign up to serve in the US military.

In terms of Guam, in a story that my friend will be coming out with soon, I think she has a line, which can explain to us more about this dynamic. Speaking on behalf of Chamorros over the past century she writes, in order to explain where we have come from, and who we are, that "we are war stories."

We have lived lives and have inherited lives which are innundated with war and wars. I manaina-ta survived World War II, and their scars and trauma becomes our patriotism, our feelings of debt, our feelings of intimacy and dependency upon the United States. The war becomes the central event in why Chamorros became Americans, why they need to be Americans. Even if we don't want to be, and constantly feel like we are mistreated by the United States, the war looms over us, a seething presence that cannot ever be dismissed.

We are an unsinkable aircraft carrier, we are the USS Guam, we are the tip of America's spear, we are Fortress Guam. After World War II, the US was determined to follow Alfred Mahan's suggestion that Guam be hammered into becoming America's "Gibraltar" in the Pacific. The destruction of World War II, the massive land takings in the late 1940's, the slow building of more and more military infrastructure on the island, and finally the decision to transfer a military force out of South Korea and Okinawa to the island, are all gestures that make this transformation real.

We are an unsinkable aircraft carrier, we are the USS Guam, we are the tip of America's spear, we are Fortress Guam. After World War II, the US was determined to follow Alfred Mahan's suggestion that Guam be hammered into becoming America's "Gibraltar" in the Pacific. The destruction of World War II, the massive land takings in the late 1940's, the slow building of more and more military infrastructure on the island, and finally the decision to transfer a military force out of South Korea and Okinawa to the island, are all gestures that make this transformation real.

The oppressiveness of all these militaristic nicknames for Guam is not accidentally or simply cute, it is an effect of how soaked we, our histories, our memories, our families, our culture is with war and the military.

Earlier this year the Washington Post came out with an article titled "Guam's Young Steeped in History, Line Up to Enlist." The most basic point that this article makes is to answer the earlier question I posed. Why do Chamorros serve and support the military so forcefully? Because their history tells them to. Because if we look back at the 110 year relationship that we have with the United States, and around what issues or events Guam appears to "matter" or is "mentioned," then the issue that makes Guam, that creates it as a point which is visible, worth mentioning, or just as something which in the vast "emptiness" of the Pacific, which means something, is war, is military actions, military needs. Guam appears in American history books around wars, 1898 and 1941-1944. It appears in newspapers around the US when military is moved onto it or taken from it. It receives attention from the Federal Government based on how strategically important it is. If you take a step back and bring together all of these moments, these mentions, then it is very clear that Guam's role in the world, and therefore the Chamorro's role in the world and in the "American family" is to function as a conduit, a tiny little point through which America can project its military might.

Basically, what you can take from this post so far is that I know alot about how militarized Guam and Chamorros are. How much the war and the military plays and has played in shaping who we are and who we feel we must be.

I have often stressed to both Chamorros and non-Chamorros, that in the history of Guam, in our "culture" we find plenty of reasons both to love the United States as well as to hate it. What this history of military affinity and service shows is that the way we have long perceived our culture and history is skewed to continually support the "loving the United States" dimension of our past and present.

I have often stressed to both Chamorros and non-Chamorros, that in the history of Guam, in our "culture" we find plenty of reasons both to love the United States as well as to hate it. What this history of military affinity and service shows is that the way we have long perceived our culture and history is skewed to continually support the "loving the United States" dimension of our past and present.

But, given the Catholic roots of Chamorro culture and belief today, and the experiences of so many Chamorros, of war and occupation, we find enough there for a very strong and vibrant anti-war Chamorro identity. An identity which has known war, has known that destruction and is therefore not committed to further war and militarization, but is determined instead to foster peace.

I will continue to dream about this sort of shift in Chamorro consciousness, and in my work and activism I will continue to try and make it possible. What set me on this course for writing this post today, was a short dialogue from the New Zealand film Utu.

While I was at the airport waiting for my plane to board, I saw this homage, downstairs from the security screening area. It is an homage to all the soldiers that have died from Micronesia in Iraq, Afghanistan and Africa, in this always growing and expanding War on Terror.

Ni' ngai'an na bei maleffa i sinangan as Borat, annai ilek-na "War of Terror."

Ni' ngai'an na bei maleffa i sinangan as Borat, annai ilek-na "War of Terror."When I gave my presentation at UC Riverside, I made clear to the students there, that if they want to find what political community or entity of the United States has the highest rate of members killed in US wars since 9/11, you don't look at any particular state or territory, but you have to look at what has long been called America's Insular Empire. This empire is comprised of islands in both the Pacific and the Caribbean, which are all territories of the United States, and rather than having formal roles in the US Federal Government, are instead administered through a colonial tag team between the Department of the Interior and the US Congress.

You can find evidence of this empire, and its constitution, or how it is brought together on the Department of Interior, Office of Insular Affairs website. There they have a page titled "Fallen Heroes in the War on Terror from OIA's Insular Areas." As the title indicates, you can find here a list of all of the dead soldiers from American Samoa, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, the CNMI, Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia. Although American Samoa in particular can claim the mantle of having the highest rate of KIA amongst all American communities, when you combine all of these territories together, they nonetheless form an imposing list of almost 60 casualties.

You can find evidence of this empire, and its constitution, or how it is brought together on the Department of Interior, Office of Insular Affairs website. There they have a page titled "Fallen Heroes in the War on Terror from OIA's Insular Areas." As the title indicates, you can find here a list of all of the dead soldiers from American Samoa, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, the CNMI, Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia. Although American Samoa in particular can claim the mantle of having the highest rate of KIA amongst all American communities, when you combine all of these territories together, they nonetheless form an imposing list of almost 60 casualties.

When I share stories in the states, of America's colonization of Guam, and mix in both the bad with the good that it has brought to the island, people often then question me about why then, do Chamorros serve? Why do they choose to fight for a country which is and isn't theirs? A country which has done just as much good for them as bad?

When I share stories in the states, of America's colonization of Guam, and mix in both the bad with the good that it has brought to the island, people often then question me about why then, do Chamorros serve? Why do they choose to fight for a country which is and isn't theirs? A country which has done just as much good for them as bad?All of the different territories, for very different historical and contemporary reasons could have different answers. Each could claim to have some similar experiences in their colonial or neocolonial relationship to the United States, but there are still very stark differences. But given their exceptional positions today, their is still plenty of room for questions as to why people in these islands would be so willing to sign up to serve in the US military.

In terms of Guam, in a story that my friend will be coming out with soon, I think she has a line, which can explain to us more about this dynamic. Speaking on behalf of Chamorros over the past century she writes, in order to explain where we have come from, and who we are, that "we are war stories."

We have lived lives and have inherited lives which are innundated with war and wars. I manaina-ta survived World War II, and their scars and trauma becomes our patriotism, our feelings of debt, our feelings of intimacy and dependency upon the United States. The war becomes the central event in why Chamorros became Americans, why they need to be Americans. Even if we don't want to be, and constantly feel like we are mistreated by the United States, the war looms over us, a seething presence that cannot ever be dismissed.

We are an unsinkable aircraft carrier, we are the USS Guam, we are the tip of America's spear, we are Fortress Guam. After World War II, the US was determined to follow Alfred Mahan's suggestion that Guam be hammered into becoming America's "Gibraltar" in the Pacific. The destruction of World War II, the massive land takings in the late 1940's, the slow building of more and more military infrastructure on the island, and finally the decision to transfer a military force out of South Korea and Okinawa to the island, are all gestures that make this transformation real.

We are an unsinkable aircraft carrier, we are the USS Guam, we are the tip of America's spear, we are Fortress Guam. After World War II, the US was determined to follow Alfred Mahan's suggestion that Guam be hammered into becoming America's "Gibraltar" in the Pacific. The destruction of World War II, the massive land takings in the late 1940's, the slow building of more and more military infrastructure on the island, and finally the decision to transfer a military force out of South Korea and Okinawa to the island, are all gestures that make this transformation real.The oppressiveness of all these militaristic nicknames for Guam is not accidentally or simply cute, it is an effect of how soaked we, our histories, our memories, our families, our culture is with war and the military.

Earlier this year the Washington Post came out with an article titled "Guam's Young Steeped in History, Line Up to Enlist." The most basic point that this article makes is to answer the earlier question I posed. Why do Chamorros serve and support the military so forcefully? Because their history tells them to. Because if we look back at the 110 year relationship that we have with the United States, and around what issues or events Guam appears to "matter" or is "mentioned," then the issue that makes Guam, that creates it as a point which is visible, worth mentioning, or just as something which in the vast "emptiness" of the Pacific, which means something, is war, is military actions, military needs. Guam appears in American history books around wars, 1898 and 1941-1944. It appears in newspapers around the US when military is moved onto it or taken from it. It receives attention from the Federal Government based on how strategically important it is. If you take a step back and bring together all of these moments, these mentions, then it is very clear that Guam's role in the world, and therefore the Chamorro's role in the world and in the "American family" is to function as a conduit, a tiny little point through which America can project its military might.

Basically, what you can take from this post so far is that I know alot about how militarized Guam and Chamorros are. How much the war and the military plays and has played in shaping who we are and who we feel we must be.

But...I constantly wish that this wasn't the case. Olaha mohon na sina matulaika este.

I have often stressed to both Chamorros and non-Chamorros, that in the history of Guam, in our "culture" we find plenty of reasons both to love the United States as well as to hate it. What this history of military affinity and service shows is that the way we have long perceived our culture and history is skewed to continually support the "loving the United States" dimension of our past and present.

I have often stressed to both Chamorros and non-Chamorros, that in the history of Guam, in our "culture" we find plenty of reasons both to love the United States as well as to hate it. What this history of military affinity and service shows is that the way we have long perceived our culture and history is skewed to continually support the "loving the United States" dimension of our past and present.But, given the Catholic roots of Chamorro culture and belief today, and the experiences of so many Chamorros, of war and occupation, we find enough there for a very strong and vibrant anti-war Chamorro identity. An identity which has known war, has known that destruction and is therefore not committed to further war and militarization, but is determined instead to foster peace.

I will continue to dream about this sort of shift in Chamorro consciousness, and in my work and activism I will continue to try and make it possible. What set me on this course for writing this post today, was a short dialogue from the New Zealand film Utu.

Ya-hu este na kachido, lao taya' tiempo-ku pa'go para bai tuge' mas put Guiya. Otro biahi siempre.

In the film, a Maori soldier serving in the British military in New Zealand defects and declares war on the white settles, after he finds his village destroyed by the same military he is serving in. The film is far more complex than my descripton here will allow, but this will have to do for now (sa' esta gof chatangmak guini). As he wages war against white settler society and the military that protects their "claims" to the land and its people, he begins to inspire other Maoris serving in the military to join his cause. After an exchange between two Maori soldiers in which the loyalties of one of them is unclear, meaning he may or may not leave soon to join the resistance, a white officer appears to find out what is going on.

In the exchange that follows, I found one of the hopes that I have of everyone in the United States, not just Chamorros. A hope that some of the very fundamental assumptions that they have about the military, its role in society, its role in the world, be questioned, be really re-examined and thought through again. On Guam, people have very positive ideas about what the military is, what it does in Guam and elsewhere. They see it as the thing which makes life possible. It protects, brings in money, provides security, provides discipline, helps the environment, provides humanitarian aid, makes a better world possible. But the military is also something which ruins things, which poisons lands, lives, which destroys countries, islands, peoples. Destruction, just as much as defense is what a military is supposed to do, and around the world and in our own corner of the Paciifc, the US military has shown that for good or for bad it is very accomplished at that. I just wish, that people would begin to consider whether or not all that positivity is justified, whether or not its true or real, whether or not it does in fact help or hurt those promises of a better world? I think, in particular Guam would be better served if we were able to dis-associate our interests from what the US military wants from us, when we determine how to make our island a better place. Sometimes they might be the same, but sometimes they might not be, and I worry that given the overly patriotic position of Guam today, it never even occurs to most people that there could be a distinction, a difference or a conflict.

In the exchange that follows, I found one of the hopes that I have of everyone in the United States, not just Chamorros. A hope that some of the very fundamental assumptions that they have about the military, its role in society, its role in the world, be questioned, be really re-examined and thought through again. On Guam, people have very positive ideas about what the military is, what it does in Guam and elsewhere. They see it as the thing which makes life possible. It protects, brings in money, provides security, provides discipline, helps the environment, provides humanitarian aid, makes a better world possible. But the military is also something which ruins things, which poisons lands, lives, which destroys countries, islands, peoples. Destruction, just as much as defense is what a military is supposed to do, and around the world and in our own corner of the Paciifc, the US military has shown that for good or for bad it is very accomplished at that. I just wish, that people would begin to consider whether or not all that positivity is justified, whether or not its true or real, whether or not it does in fact help or hurt those promises of a better world? I think, in particular Guam would be better served if we were able to dis-associate our interests from what the US military wants from us, when we determine how to make our island a better place. Sometimes they might be the same, but sometimes they might not be, and I worry that given the overly patriotic position of Guam today, it never even occurs to most people that there could be a distinction, a difference or a conflict.

Here's the dialogue:

Lt. Scott: Trouble?

Wiremu: Maybe (translated)

Lt. Scott: Is he going too?

Wiremu: Sir, will these help to make a better world?

Lt. Scott: I doubt it (translated)

Wiremu: Then does it matter which side we're on?

Comments