De-Nationalization and Negative Universality

In its Big Ideas of 2006 issues, AdBusters named Alain Badiou as "The Philosopher of the Year." This passage from their short article on the reception of his work in the United States is what brought about the following post:

"To take just one example, postmodern thought has been obsessed by the figure of the cultural other. However, the abstract, absolute character of the postmodern idea of the other has insured that any attempt to reach out will always be viewed as just another form of domination. Badiou has brought a withering philosophical criticism to bear on the notion that cultural difference can be thought of in terms of overarching generalities about metaphysics, arguing instead that the social field that structures otherness is a matter of specific "situations," organized around certain concrete, tendentious exceptions, with political "truth" being a matter of bringing these exceptions to light. Thus, while postmodern philosophy dead ends into the abstract, political correct call for "respect" of difference, Badiou's philosophy yields a demonstration of the potential a fight for immigrant rights can have."

The crucial point here is that universality is not primarily positive, but rather negative. It is not a timeless, eternally structuring principle, point or class, but the gesture of universalizing a certain abject point. A point whose very universalization or "incorporation" can no longer be considered to be mere incorporation, as this gesture will require something different to emerge, a revamping, a potentially radical reformatting.

We find this potential in the tenuous relationship the United States has with "illegal" immigrants. The rhetoric of not rewarding crimes or illegal behavior does not do away with both the economic necessity nor the racial desire/fantasies that these bodies embody and stimulate. Because of this entanglement of obviously disjunctive and yet complementary desires, there is the possibility of a collision between the concepts of "citizen" and "illegal immigrant." One the "univeral" position, the other a position of abjection, and therefore a site of potential negative universality.

In every political space, there is the hegemonic position of universality, whose interests are most commonly read as the interests of all. In the United States for example, through media texts we know that it is the middle class. For example, during Presidential campaigns, the issues candidates discuss are always discussed as if they are everyone's issues, but in reality they are molded based on the imagination of the middle class. (Why else would economic health be based on how many peoplre are falling out of the middle class?)

The point which differentiates this form of universality as radical as opposed to merely liberal, is the "illegal" aspect. The immigrant body is a redeemable body, one which can in some way be assimilated, because its entrance is approved through the law and the nation. Although the bodies themselves may bring with them different histories which in different ways threaten the "original sinlessness" of the nation (Vietnamese, Filipinos, El Salvadoreans, etc.), their presence is still easily translated into the dominant racial fantasies such as "the subject supposed to immigrate," which is ultimately a crucial fantasy for the nation's reproduction (a Mexican is just someone who hasn't crossed the border yet).

This radical gesture is not a search for the position which makes the current form or framework merely more inclusive, merely more democratic, which is precisely what the Civil Rights movement accomplished. A request for you to let us occupy the same position as you. A recognition of the structure, and a demand which is based on inclusion in that structure as opposed to its transformation.

It is instead, searching for the truth attached to a particular position which can break the position to which it will be incorporated, can change the dialectic and start something else.

If the position of the "illegal" immigrant can become universalized, it might represent such a rupture. Where a point beyond the scope of the nation becomes hegemonic, becomes the structuring principles, which allows community to be re-imagined and re-shaped.

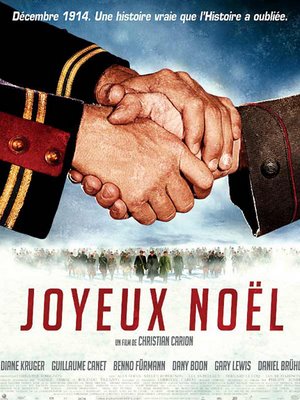

Most recently, I saw this in the film Joyeux Noel, which presents an amalgamation of different  denationalized moments along the English, French and German trenches in World War I. On Christmas Even and Christmas Day 1914, a number of incidents took place where soldiers crossed the no man's land between trenches to celebrate Christmas together. This acts are presented to us across the nationalist demonizing that always takes place prior to war, where your enemy is the enemy of God, the embodiment of all things evil, and therefore it is your duty to protect and defend civilization against them. Through this lens, these nation/border crossings are truly inspirational.

denationalized moments along the English, French and German trenches in World War I. On Christmas Even and Christmas Day 1914, a number of incidents took place where soldiers crossed the no man's land between trenches to celebrate Christmas together. This acts are presented to us across the nationalist demonizing that always takes place prior to war, where your enemy is the enemy of God, the embodiment of all things evil, and therefore it is your duty to protect and defend civilization against them. Through this lens, these nation/border crossings are truly inspirational.

But a sort of killjoy question persistently nagged me throughout the film. Why is it that the soldiers from France, England and Germany could come together on Christmas like that? It is because there is an easily identifiable point which cuts across their trenches and cultures, and that is a common European identity through religion. It is this alternative point of universality, which all the involved nations must make use of to constitute themselves as wisen and ancient, which also provides a risky potential for undermining the process of absolute enemy making and demonizing. This comity is possible precisely because of the way the soldiers recognized themselves in a third point, which lay outside of, beyond and before each of them.

Notice the difference between those instances and American soldiers in the current War in Iraq. In the discourse of the troops who are encountering the people, culture and habits of their enemy, it is not that we share some other point, which calls into question who both of us our, but rather, that these Iraqis desire who we are, what we have. Whether it be education, technology, American Idol, or freedom. Or as Zizek put it appros the protests in Tinnamen Square, when you scratch away the Yellow, you find an American."

But then again, is the inability for troops in Iraq to de-nationalize themselves because the enemy which we fight is not part of any particular nation? The enemy of American troops in Iraq isn't the Iraqis, but rather "terror" and "terrorism." Is it for this reason that Americans cannot denationalize with Iraqis since this very framework deprives them of sovereignty, and by theoretical default makes them people in need of a nation?

Published on Tuesday, April 11, 2006 by the New York Daily News

Out From the Shadows

by Juan Gonzalez

Jose Chicas had longed for this moment ever since 1982, when as a young man he fled the civil war in his native El Salvador and crossed illegally into California.

Over all those years of pickup construction jobs for low wages, Chicas kept dreaming that all hardworking immigrants like himself would one day step out of the shadows, cast off their fears of being deported and finally demand respect.

Yesterday afternoon, Chicas stood proudly on the back of a pickup truck watching his dream come true in the brilliant spring sunshine of lower Manhattan.

Around him were hundreds of fellow members from Local 79 of the Laborers' International Union, all signing in with Chicas for their union's contingent at the big immigrant rights rally at City Hall. He carefully distributed the union's bright orange T-shirts to each of them.

By 5 p.m., the throngs from the big City Hall rally stretched north along Broadway for more than 15 blocks, as police seemed surprised by the size of the turnout.

The torrent of chanting faces and flags stretched past Canal St., paralyzing rush-hour traffic in every direction.

The same scene was repeated all across America, as hundreds of thousands of janitors, hotel workers, gardeners, nannies and unskilled factory hands streamed into the streets of more than 100 cities.

Never - not even at the height of the civil rights movement of the 1960s - has there been such an outpouring of our nation's huddled masses as during the past few weeks over this immigration debate.

Don't buy for a moment the nonsense that these protests don't matter, that all these marchers are illegal immigrants who can't vote so the politicians can simply ignore them.

When black people shook the South with their protests, they couldn't vote, either.

As for Chicas, it took him 15 years, but he finally obtained a green card in 1997. Now a staff organizer with Local 79, the union of demolition workers, he has become a fervent advocate for legalization of the country's 11 million undocumented immigrants.

And then there is Assemblyman Adriano Espaillat (D-Washington Heights). Espaillat came to this country several decades ago, overstayed his visa and was once an illegal immigrant himself.

Today he is one of the most respected Dominican leaders in this town and helped organize a half-dozen separate contingents from northern Manhattan for yesterday's march.

Then there is Marienela Jordan, who came to New York with her family from the Dominican Republic in 1979, a few weeks after Hurricane David.

"The storm devastated the economy, and there was no work," Jordan told me yesterday. She, too, overstayed her visa and became undocumented for a time. Today, she is not only a citizen but heads the Office of Latino Affairs for Nassau County Executive Tom Suozzi.

And so it is with so many legal residents and even American citizens. Having once been branded "illegal" themselves, they are furious at how some Washington lawmakers are eager to turn desperate workers into felons and tear apart whole families in the process.

Backers of an immigration crackdown will tell you there's a huge chasm between legal and illegal immigrants.

Our Native Americans would disagree. They still say all of us were illegal once. The descendants of the original Mexican settlers of Texas and California swear Sam Houston, Davy Crockett and all their progeny should never have been allowed to cross the border.

At least Chicas and the latest 11 million didn't come here with guns, determined to impose their will. They came with hands outstretched and eager to work for whatever someone would pay.

Now that they've stepped out of the shadows, all they want is a little respect from the country they love.

Juan Gonzalez is a Daily News columnist. Email: mailto:jgonzalez@edit.nydailynews.com

© 2006 Daily News, LP

###

Comments