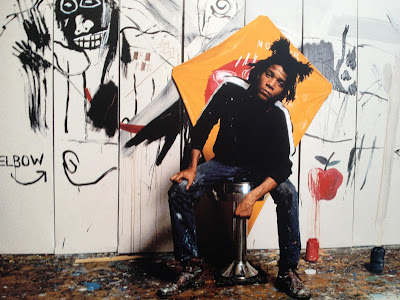

Jean-Michel Basquiat

I don't paint as much as I used to, but I'm still an artist gi korason-hu.

Achokka' ti mamementa yu' kada diha, manhahasso yu' todu tiempo put pinenta yan atte.

I have been inspired by many artists over the years, especially when I was an undergraduate and graduate student at UOG.

At that time, I was painting a great deal and displaying and selling my artwork around the island.

One of the biggest influences on me, and something which made me the butt of a great deal of "måtai na pepenta" na jokes, was my looking up to Jean-Michel Basquiat.

He was one of the consummate bohemian artists, who challenged artist norms in his time, was used by the artworld during his short life, and then died.

When I first created an email account for myself in 1998, I was so enamored with Basquiat, that I didn't use my name, but instead blended our names together.

Rather than mlbevacqua, I instead entered mlbasquiat.

It has created a lot of confusion over the years as people who haven't met me in person but only over email, sometime assume that my last name is Basquiat and greet me and address me as Michael Basquiat or Dr. Basquiat or Mr. Basquiat.

Below is a long article about Basquiat that appeared in Vanity Fair a few years ago.

***************************

“Burning Out”

by Anthony Haden-Guest

Vanity Fair

April 4, 2014

Much has been written about the heroin-linked death of

Jean-Michel Basquiat. But one voice was missing—that of the wildly talented,

wildly extravagant painter himself. Anthony Haden-Guest interviewed America’s

foremost black artist in the last stages of his blazing trail, as he careened

between art dealers and drug dealers.

At about one in the morning on Friday, August 12, I saw

Jean-Michel Basquiat at M.K. I was surprised. The extravagantly talented young

painter, once among the more visible night birds of Manhattan’s haute bohème,

had become famously reclusive. The reason was not a secret. He was locked in a

battle with heroin.

The upper floor of the club is baroquely lit, but he looked

changed—midriff fuller, face plumper. “That is you, Jean-Michel?” I asked.

“Yeah . . . ” A front tooth was missing with disconcerting

effect. His eyes were remote, his smile wan. Oh, well. Basquiat was notoriously

moody. I moved on, past the pool players, down to Bryan Ferry’s postconcert

party on a lower deck.

Basquiat had arrived, typically, with a couple of young

women, both stunning, Kelly Inman, a makeup artist, who lived in the basement

below his studio, and Kristen Vigard, a young singer, whose long red hair was

now very short and bleached white, and he had only come at their urging. “We

wanted to get him out of the house,” Kelly remembers.

One of the people that Basquiat bumped into was a close

friend, Kevin Bray, an N.Y.U. film student. Bray, like so many, had supported

Basquiat in his struggle with his addiction, and had been delighted when the

artist had returned from Hawaii ten days before, ebulliently announcing that he

had finally kicked the habit. “But I could tell he was really high,” Bray says.

“I was very discouraged.”

Inman and Vigard were wandering around somewhere. Impulsive

as always, Basquiat suggested to Bray that they leave. He wanted company.

Basquiat took a cab the twenty blocks downtown to his Great Jones Street loft,

Bray bicycled. “We sat, and drank Gatorade,” he says. Recently, Basquiat had

been loquacious with his close friends about his plans for a new life, which

were colorful, if sometimes contradictory.

Certainly he was leaving Manhattan. Almost certainly he was,

at the age of twenty-seven, giving up the mercantile and treacherous art world.

Perhaps he would be a writer. Perhaps he would take what he called an “honest

job,” like running a tequila business in Hawaii. The following Thursday, he was

leaving for the Ivory Coast, where he was expected in a Senoufo village five

hundred miles inland from the capital, Abidjan. Here he would take a tribal

cure for the heroin— and other New York wounds.

Tonight, though, Basquiat was quiet. “He didn’t really want

to talk about anything,” Bray says, “and soon he started nodding. And I said,

I’m sorry—I just can’t stay around. I wrote kind of a weird note . . . I DON’T

WANT TO SIT AROUND HERE AND WATCH YOU DIE . . . And then, YES, YOU DO OWE ME

SOMETHING. Because we have an ongoing dialogue . . . why he should stop

[drugs], why he should keep on painting . . . he never thinks people understand

the paintings.”

That agonizing present tense, when the fact of death hasn’t

quite sunk in.

Bray passed the note to Basquiat, but he was too loaded to

focus, so Bray read it aloud, and left, fuming. “Somebody who gets that high is

dying over and over and over again,” he says now.

Kelly Inman got back from M.K. at about four in the morning.

“I didn’t see Jean-Michel,” she says. “I went downstairs to bed.” She was woken

by the telephone at 2:30. It was Kevin. Jean-Michel was going with him to a

Run-D.M.C. concert that evening. Inman climbed into the bread-oven heat of the

upstairs bedroom—the air conditioner had failed, an annoyance that Basquiat,

with a characteristic twinge of paranoia, blamed on his landlord, the Warhol

estate. He was sleeping, she decided not to disturb him.

Bray rang again three hours later. Inman called, received no

response, and again climbed the stairs. Jean-Michel Basquiat was lying in a

pool of vomit. Inman felt the pulse and did what she calls “the usual things,”

but with rushing emotions—fear, frozen calm, and an odd relief that his ordeal

was over— she saw that he was dead.

The brilliant, intense life of a most remarkable artist—America’s

first truly important black painter—was over.

I had visited Basquiat several times last April. No name

marked the thick metal door that sheltered his loft from the neighborhood

derelicts and crack vendors, and the ground-floor studio/kitchen/dining room

looked both busy and cozy. The floor would always be covered with unstretched

canvases in various stages of completion, and Basquiat, with his usual

nonchalant, fuck-you, art-world attitude, would trot messily across them to

fetch me a beer or tend to the spaghetti. The place looked lighthearted, with

dark-side-of-Pop touches—portraits of Elvis and James Dean—and a giant birdcage

adorned with a rubber bat and containing the bird’s nest that he sometimes wore

to parties. The only visible artwork not by Basquiat was a portrait of him by

Andy Warhol, hanging near the sink.

The Warhol, silkscreened on a background of splotched greeny

gold, was one of the notorious “piss paintings” (mostly abstracts, created by

the interaction of urine and copper sulfate on canvas). “I didn’t know it was a

piss painting,” Basquiat told me. He later mentioned to a friend, writer Glenn

O’Brien, that the splotches were oddly predictive of his own current skin

condition, which was indeed terrible, marring his striking looks. Otherwise, he

seemed alert, even mischievous—on one visit he was wearing a girlfriend’s black

dress—and he insisted that he had his heroin problem “under control.” Beyond

that, he was reticent about it.

He was anything but reticent, though, about his upbringing,

which he painted in the darkest terms. Basquiat would often talk of beatings at

the hands of his father, of his mother being hospitalized for depression, of

their marriage breaking up when he was seven. “I had very few friends,” he told

me. “There was nobody I could trust. I left home when I was fifteen. I lived in

Washington Square Park. Of course my father minded. Jesus Christ!”

The tormented picture was obviously deeply felt, but lengthy

meetings with Jean-Michel’s father, Gérard Basquiat, suggest that it doesn’t

wholly jibe with reality. Basquiat Sr. comes from a solidly bourgeois family in

Haiti which incurred the ire of “Papa Doc” Duvalier. “My mother and father were

jailed,” he says. “My brother was killed. I came to America when I was twenty.”

Here, he became an accountant, married Matilde, a woman of Puerto Rican stock,

and had three children, at three-year intervals, Jean-Michel, Lisane, and

Jeanine. He worked hard, and prospered. “Jean-Michel, for some reason, liked to

give the impression that he grew up in the ghetto,” Gérard Basquiat says,

adding, “I was driving a Mercedes-Benz.” They lived in a four-story brownstone

the family owned in Boerum Hill, a couple of blocks from the Brooklyn Academy

of Music.

At six, Jean-Michel had been hit by a car, and had his

spleen removed. This didn’t prevent him from becoming a school champion in the

sprint, but it was to trouble him later. The boy was bright, and intent on

becoming a cartoonist, but very difficult. He went to a sequence of schools,

and finally wound up in the City-as-School, an excellent establishment which

specializes in the talented and contrary. Here, actually, he had numerous

friends. “Jean-Michel was very rebellious,” his father says, “very rebellious.

He was expelled for throwing a pie in the face of the principal.” It was June

1978. Sometimes Gérard Basquiat “spanked”—his word— his troublesome son, but

the fact is Jean-Michel stayed in fairly constant touch with both parents. He,

his father, and his father’s companion of twelve years, an attractive

Englishwoman called Nora, would go to the Odeon and Mr Chow’s, and Jean-Michel

once took Andy Warhol to a dinner party in Brooklyn.

“My father could be severe. It came from his Haitian

background,” says Lisane Basquiat. But he was a loving father, and she is glad

of the strictness now. “I never realized Jean-Michel held on to so much.

Childhood fights. All those little things,” she says. “He was just a boy who

didn’t grow up,” says their father.

But this tendency to hoard resentment was not apparent in

the inquisitive, slyly humorous seventeen-year-old who started showing up in

Manhattan, at first mostly with school friend Al Diaz. Soon he was noticeable

in the hyperactive downtown scene, where he had a brief fascination with

bisexuality. His artistic ambitions were still unfocused. He sold painted

T-shirts to tourists in Greenwich Village. Martin Aubert, another school

friend, remembers Basquiat talking about how much money he could make. “He

craved parental approval,” Aubert says. Meanwhile, Basquiat slept on the crash

circuit of sofas, floors, and the beds of friendly women. “I was a cute kid,”

he said.

Along with his raw talent, he had a shrewd tactical eye.

Graffiti was very much around, although, as painter Kenny Scharf puts it, “it

wasn’t really connected with art yet.” Hence, the birth of Samo. The messages

that began appearing on Manhattan walls in 1978 ran from the simplistic SAMO

FOR THE ART PIMPS to the poetically ominous PAY FOR SOUP, BUILD A FORT, SET IT

ON FIRE. They were signed Samo, with a copyright symbol saucily appended. “Samo

meant same old shit,” Basquiat told me. “It was kind of sophomoric. It was

supposed to be a logo, like Pepsi.”

Basquiat was always drawn to the idea of collaboration—Al

Diaz, whose graffiti tag was Bomb 1, was a partner—but Basquiat was the

conceptual leader. “You didn’t see Samos up in Harlem,” observes Fred

Brathwaite, a.k.a. graffiti artist/rapster Fab 5 Freddy, a close friend of

Basquiat’s and a fellow Brooklynite. “They were aimed at the art community.

Because he liked that crowd, but at the same time resented that crowd.”

His next step forward was through music. In late 1979

Basquiat became a member of Gray, a band that a fellow member, Michael Holman,

describes as “between an art band and jazz. ‘Gray’ was Jean’s idea. I think it

had to do with the color of a piece of paper that was hanging up. We said

great. It wasn’t like the Angry Toads or something.” Fred Brathwaite remembers

the first gig. “It was at the Mudd Club. David Byrne was there. Debbie Harry.

It was a real Who’s Who. Everyone was there because of Jean . . . Samo’s in a

band! . . . They came out and played for just ten minutes. Somebody was playing

in a box. It just blew me away.”

Basquiat was also making art. He would draw on Mudd Club matchbooks,

and sell them for a dollar. He became briefly associated with Canal Zone, a

group that included Fab 5 Freddy and fellow graffitist Lee Quinones. “We were

lent a loft,” Brathwaite says. “Jean-Michel would be in the back room, making

‘baseball cards.’ He would cut up these photographs, lay them down on graph

paper, and draw on them. He would color-Xerox them on Spring Street, and sign

them Samo or Manmade. Original limited-edition-type things.” Basquiat hawked

them on the street for a few dollars. Alert to the fact that Kenny Scharf had

made a splash by showing work at Fiorucci, he talked the fashion store into

seeing him. “He bought oil paint on the way,” painter Keith Haring says. “He

smashed it open on the street, and made a painting. In Fiorucci, he got paint

on the carpet, on the couch, and all over. They threw him out. For him, this

was a great triumph. He sort of wanted them to buy some color Xeroxes, but at

the same time, he had a disdain for it.”

Basquiat approached Andy Warhol in a downtown restaurant

where he was eating with Henry Geldzahler, and sold him one of these Xeroxes.

Warhol was Basquiat’s most specific obsession. Chris Sedlmayr, an electrician

who had met Basquiat at the Mudd Club, gave him odd jobs such as an

installation in the Castelli gallery, where he gleefully scribbled a few

furtive Samos on tubes containing Warhol silkscreens. Fred Brathwaite remembers

hanging out with Basquiat, John Sex, and some other downtown types outside Club

57, and discussing the idea of doing a performance piece based on the Factory.

Somebody asked, “Who will play Andy?”

“I will,” Basquiat insisted.

Visiting the actual Factory, he sold Warhol a few more

Xeroxes for a dollar. Warhol gave him four or five cans of expensive Liquitex

paint, which he slathered on more clothing and sold at Patricia Field’s shop on

Eighth Street.

Basquiat was by then a natural choice to star in a movie

about downtown called The New York Beat. It featured Debbie Harry, was financed

by Rizzoli, directed by the photographer Edo (later questioned in the Crispo

case), written by Glenn O’Brien, and based loosely on Basquiat’s own life. “It

never came out,” O’Brien says, “because a couple of the Rizzolis went to the

slammer.”

The art Basquiat painted for the movie was a departure. “I

hadn’t done anything good until then,” he told me. “Actually, my basic

influence had probably been Peter Max.” But by now Basquiat had voraciously

assimilated a whole new world of art, from Monet’s water lilies to Cy Twombly.

He devoured Picasso’s Guernica, and later noted the irony of coming to African

art via the Spaniard.

“I want to make paintings that look as if they were made by

a child,” he told Fred Brathwaite, Picasso-like, in the street.

While he was living in the movie production office above the

Great Jones Café, Basquiat painted his first figurative works. Then he moved in

with a girlfriend, Suzanne Mallouk, his age and half Palestinian, half English.

Mallouk allowed herself to be dominated. “I paid the rent waitressing,” she

says. “I supported him.” Now he set fanatically to work.

“In 1980 I heard that Samo was making this really great

art,” says Jeffrey Deitch, an art consultant for Citibank. He went to see. “I

couldn’t believe it. Every surface was covered, the refrigerator, the tables.

He had dozens of these little drawings on typewriter paper. The paintings were

on doors and window frames taken off the street.”

Basquiat was now both ubiquitous and noticeable around lower

Manhattan. For a while he had sported a bleached blond mohawk, but soon grew a

crown of dreadlocks. “And he would wear this paint-spattered smock,” says Fred

Brathwaite. “You could see the look on people’s faces: I don’t want to walk by

this guy!”

In early 1981, Diego Cortez included a group of Basquiats in

the seminal “New York/New Wave” show at P.S. 1. The show featured more than

five hundred artists, but the pieces by Basquiat—who showed as Samo—were

standouts. A style had suddenly fallen into place. The work is graphic, crudely

drawn with oil sticks, often featuring bits of found writing—downtown street

signs, whatever—and always using images at once witty and disturbing, like

those used to propitiate powerful forces. No wonder, alongside his more formal

sources, such as Leonardo’s codices, Basquiat sometimes mentioned voodoo.

“The common reaction, which was mine,” says Alanna Heiss,

the director of P.S. 1, “was that this was the new Rauschenberg. It was a

really clichéridden reaction, in terms of tingling, goose bumps, all the words

we use all the time, but this time it was really true.” It was at P.S. 1 that

Basquiat made converts of such influential voices as Henry Geldzahler and Peter

Schjeldahl, whose review in The Village Voice singled out Robert Mapplethorpe

and “Jean-Michel Basquiat, a twenty-year-old Haitian-Puerto Rican New Yorker.”

Alanna Heiss recalls that, “by the end of the show, people were trying to find

Jean-Michel to buy pictures. Things had gone a bit bananas already.”

Old identities folded. Samo’s penultimate graffito was: LIFE

IS CONFUSING AT THIS POINT . . . Basquiat then had a “falling-out” with Al

Diaz, and went around downtown writing SAMO IS DEAD. He also pulled out of

Gray. “He was on this ego trip,” says band member/artist Vincent Gallo,

“schmoozing with Eno and Bowie instead of taking care of band business.”

Basquiat, David Byrne, and Arto Lindsay of DNA briefly rehearsed as a group

named for one of Basquiat’s obsessions: Famous Black Athletes.

Basquiat’s first dealer was Annina Nosei, an Italian woman

with a nose for talent and a SoHo gallery. “I was doing this show called

‘Public Address,’ ” she says. “It was a group show. I said, Are you sure you

fit in? He said, Yes, yes, I fit, I fit. He said his work was addressing the

public, although it was poetical, and intimate. I gave him the money to buy a big

canvas.” Among the other artists that Nosei was showing for the first time were

Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, and Keith Haring. “They were in the front room,”

says Nosei. “Jean-Michel had a whole room, with five or six pieces, so it

became Jean-Michel and the others.”

They all sold, at $2,500 apiece. “After that success, we

planned a one-man show for March 1982,” Nosei says, “but he needed a place to

paint.” She offered him the space in the basement of the gallery, which he

cheerfully accepted. “It was the first time I had a place to work,” he told me.

“I took it. Not seeing the drawbacks until later . . . ”

The “drawbacks” were firstly practical. “She used to bring

collectors down there, so it wasn’t very private,” said Basquiat. “I didn’t

mind. I was young, you know.” The greater drawback was symbolic. Brathwaite

remonstrated with him: “I said, A black kid, painting in the basement, it’s not

good, man. But Jean knew he was playing off this wild-man thing. Annina would

let these collectors in, and he would turn, with the brush in his hand, all

wet, and walk towards them . . . real quick.” On the other hand, Yann Gamblin,

the French photographer, recalls Basquiat totally ignoring his visitors while

attacking three canvases more or less at once.

Annina Nosei, slipping into a parental role, advanced him

cash to live on. Typically he would spend it on lunch at Dean & DeLuca, the

pricey SoHo grocery. Gérard Basquiat recalls a dinner with his son and Nosei at

Hobeaux. “I’m like a mother to Jean-Michel,” the dealer told Basquiat père. “I

thought, Oh my god, she’s finished,” he says.

Patti Astor, who started the Fun Gallery in the East Village

as an anarchic reaction to the white-walled SoHo machine, says the Nosei show

was one of Basquiat’s best ever, but is wry about the opening. “The fashion

that year was for these hideous, green-dyed mink coats. It was raining, and the

whole gallery was filled with these soaking-wet, green mink coats. Jean-Michel

was hiding in the back. I couldn’t go and say hi, because I couldn’t face that horrible

phalanx. I felt that Jean-Michel needed a place to show where he could really

have some input.”

Basquiat—who would always veer from receptivity to intense

mistrust— did show at the Fun Gallery. Shortly before the opening, Astor invited

various artists to a pumpkin-carving party. “Kenny [Scharf], Keith [Haring],

and Jean-Michel were all sitting, doing it. Julian [Schnabel] came over, and he

said, Oh, this is stupid, but then he sits down, and carves this pumpkin, and

he’s so proud of it, he wants to have it cast in bronze.” The pumpkins were put

in the gallery window. The Schnabel one was stolen. “It became the most famous

pumpkin in town,” Astor says.

The perpetrator was, of course, Jean-Michel Basquiat. The

remains of the vegetable wound up in a box of white painted wood covered with

drawings and enigmatically inscribed “Vagina water,” as Basquiat’s contribution

to the “Art” installation at the club Area in May 1985, mounted as

counterprogramming to the opening of the Palladium.

The Fun Gallery show was a resounding success for Basquiat

in every way except, as he would often carp, financially. He had made his first

real money in Italy, selling ten pieces through Emilio Mazzoli’s gallery in

Modena. “Suddenly from nothing he has $30,000 in his pocket,” Astor says.

At the end of the year, Basquiat went to stay with the

dealer Larry Gagosian in Los Angeles. “I had a big house on the beach in

Venice,” Gagosian says, “and I gave him an enormous room for a studio.”

Basquiat stayed for six months, working ferociously. He developed a pattern in

which work and life, completely entwined, were both forced to the limit. There

was something childlike about his appetites. He had used so much cocaine he’d

perforated his septum. Nile Rodgers, the musician, who ran into Basquiat in the

Maxfield Blue store and gave him a ride, later found he had left half a dozen

brand-new Armani suits in the car. “He was flying out friends to stay with

him,” Gagosian says. “It was really a zoo.”

The long affair with Suzanne Mallouk was breaking up—“I

couldn’t take it anymore,” she says. “He was too overpowering.” He had embarked

on a series of relationships with young women. “He had a need to be surrounded

by blonde models,” she adds. He could be possessive and dominating, with the

usual role games, but the erotic is not a powerful element in his painted

world. “It’s a theme I never approach,” he told me. “Or hardly ever. If I see

sex in a movie, I want to turn away.” He was equally shy about his use of hard

drugs. Though he enjoyed smoking what were obviously joints in full view, few

were aware of his freebasing and dabbling with smack. “I had seen him sitting

on the steps of the Electric Circus at the end of 1980,” says Martin Aubert,

now a sessions guitarist. “He was covered with paint and shivering. He said,

I’m on heroin. I guess you don’t approve of that, but I have decided the true

path to creativity is to burn out. He mentioned Janis Joplin, Hendrix, Billie

Holiday, Charlie Parker. I said, All those people are dead, Jean. He said, If

that’s what it takes . . . ”

In later years, Basquiat would claim that he only started

shooting heroin after Warhol’s death. This was the junk lying. An ex-addict

friend of mine remembers seeing Basquiat in late 1982 at an East Seventh Street

apartment where art-world and uptown users—“no street junkies at all”—would buy

their drugs and socialize. “He had a legendary habit. It gave him a lot of

cachet. He would drop $20,000 or $30,000 at a time. We’re talking ounces, not

stuff that had been cut and put in bags. The expectation was quite general that

he wasn’t going to be around for much longer.”

Basquiat spent Christmas 1983 in Los Angeles with a

girlfriend, the then unknown Madonna. Larry Gagosian remembers, “He told me,

She’s going to be a big, big star.” Fred Hoffman, of the Hoffman Borman

gallery, took them to lunch in the Twentieth Century Fox commissary, and

remembers them glowering around, sizzling with ambition.

In the art world, at least, Basquiat had become a figure of

glittering success. He had two canvases in the Palladium’s Michael Todd Room,

and his name was dropped in gossip columns. There was a rustle of attention

when he walked into a restaurant or a club, and he was making much more money

than his friends. His success both excited and disturbed him. “From being so

critical of the art scene, Jean-Michel was all of a sudden becoming the thing

he criticized,” says Haring. He coped by profligacy. He tossed $100 in dollar

bills from a limousine window at the panhandlers on Bowery and Houston. He

ruined his designer suits by painting in them. He lent indigent friends money

and art materials. He scattered drawings and paintings around like a tree

shedding leaves. The rapacious homed in. “I worked with him a lot in Los

Angeles,” says Matt Dike, who now has a small label, Delicious Vinyl.

“Everybody was just picking up paintings and drawings. Jean-Michel was so

dusted that he didn’t know what was what.” It was also at this time that he

slashed a roomful of his own canvases.

With this relentless bohemianism went an odd yearning for

propriety. He would now stay in hotels in Los Angeles, but disdained the funky

Chateau Marmont in favor of the solidly bourgeois L’Ermitage. The lavish “art

dinners” that he threw in Manhattan were less likely to be in the downtown

eateries than in staid Barbetta’s on West Forty-sixth. John Good, who then

worked for Leo Castelli, remembers Basquiat energetically entering the world of

fine wines. “We went to Sherry-Lehmann. They were very suspicious at first, but

he whips a thousand bucks out of his pocket, trying to find the best, the

oldest bottles that they had. I said, Jean-Michel, you don’t have to drink ’61

Lafite all the time. There are a lot of cheaper ones that are very good. He

said, Yeah, but it’s not that expensive! I mean, it’s cheaper than drugs . . .

“He was always asking about [art] dealers, which were good,

which were bad. He was more ambitious than anybody ever dreamed,” says Good.

“Should I have a boxing match with Julian Schnabel?” he once asked Mallouk. And

he was uneasy when she posed for Francesco Clemente. “Who’s a better artist?”

he asked her.

“Francesco,” she told him, wickedly. “He’s more spiritual

than you are.”

One night he woke her to show her a portrait of her he’d

just finished. A snake was floating above her. “Is that spiritual enough?” he

asked.

Basquiat was just as hypersensitive in his relations with

dealers. He left Annina Nosei for Bruno Bischofberger of Zurich, a dominant

figure in the international art market. “I took him to Mary Boone. She and I

were partners,” Bischofberger says. At his grand Mary Boone opening he told his

former school-teacher Mary Ellen Lewis, “I wonder what Fred [the principal at

whom he’d thrown the pie] will think of me now. Wasn’t I the one least likely to

succeed?”

In February 1985 a shoeless Basquiat adorned the cover of The

New York Times Magazine. At first euphoric, he signed copies in the Odeon and

Area, but on reflection he decided to be offended. The title of the Times piece

was “New Art, New Money: The Marketing of an American Artist.” “As though I

didn’t do it myself,” he complained. It was just one more sign that Basquiat

was a rare black in a monochrome art world. Fred Hoffman celebrated Basquiat’s

birthday at a fancy restaurant in Beverly Hills: “I remember him looking

around, then saying to us, You know what? Everybody in this restaurant is

trying to figure out just why I should be here.”

His mood swings were intense, from sweetness and dry

intelligence to an untrusting sullenness, abrasive, prickly, sometimes

bordering on something worse. Hoffman, who was probably as close as anybody to

Basquiat then, speaks of periods of “dissociation” in which the artist would

have problems distinguishing reality from phantasms.

“One thing that affected Jean-Michel greatly was the Michael

Stewart story,” says Haring. “Suzanne was now going out with Michael Stewart,

who was a skinny black kid. He was an artist. He looked much like Jean-Michel.”

Stewart was beaten up by cops in a subway station. They claimed he had been

doing graffiti. He died of his injuries. That night Basquiat painted red and

black skulls. He told Haring about it at the Roxy club. “He was completely

freaked out,” says Haring. “It was like it could have been him. It showed him

how vulnerable he was.” (The interminable inquiry into the death of Stewart

ended with nobody being convicted.)

Basquiat’s metropolitan celebrity was as shiny as ever, but

a new chill was developing within the inner councils of the art world.

Neo-Expressionism, suddenly rather vieux chapeau, was being replaced on the

assembly line by Neo-Geo and Commodity art. “It doesn’t seem very new,”

Basquiat groused to me. “But people have a very short attention span. They’re

looking for another artist every six months. There’s only twenty good artists

in a century.”

He was also increasingly aware that he was failing to

consolidate on his first success. It was true that he had influential

supporters—at his death, Basquiats were owned by Eli Broad, Paul Simon, and

Ethel Scull, among many others— but when Basquiat deciphered the clues, the art

establishment was not anointing him. Castelli gave Haring a show—not Basquiat.

He was not represented in the Saatchi Collection. “Charles Saatchi has never

liked my work at all,” he told me. Most embittering of all, although pieces

were owned by both MOMA and the Whitney, he had never been accorded a museum

show. Some of this was paranoia induced by cocaine, but he also seemed to

embrace the martyr role. “He wore a kick-me sign,” says a friend. Basquiat’s

sourness extended to his fellow artists—only Schnabel and Clemente had been

welcoming, he felt—and he would parse reviews for condescension, the demeaning

phrase. “They still call me a graffiti artist,” he complained. “They don’t call

Keith or Kenny graffiti artists anymore.” Fred Brathwaite agrees: “Graffiti had

become another word for nigger.” What Basquiat felt he was encountering wasn’t

racism of the cruder sort, but the subtler prejudice that women artists

encounter: He wouldn’t build a career, just drop out of history, or, worse, out

of the marketplace. Burn out.

There was a convenient focus for Basquiat’s resentments: his

dealer. Later he complained that “Mary did nothing for my career. She never got

me a museum show.” In fact, Boone worked hard to build up his market, but

heroin is a formidable opponent.

Basquiat, capable of terrific work, was also alarmingly

erratic and undiscriminating. She began to doubt his capacity for “articulating

his vocabulary,” meaning develop, grow. Tensions worsened. He felt she was

behaving like another heavy parent. One friend remembers Basquiat “literally

jumping up and down, shouting, I’m the star—not Mary Boone.”

Publicly, he was having a high old time. Jonathan Scull,

Ethel’s son, who owned a limousine service and sometimes drove Basquiat

himself, remembers taking the artist to an opening—he was wearing pajamas and

that bird’s nest on his head. After the opening of Bruce Weber’s Rio exhibition

at the Robert Miller Gallery he dropped his trousers, to the astonishment of

some young women. At a Puck Building opening he tossed a stink bomb. The high

jinks, though, were increasingly fueled by heroin. He had now grown to hate

junkies and resent his addiction, but he was himself drifting out onto the dark

ocean of opiates when he found a new collaborator, an unlikely savior, and a

complaisant father.

Andy Warhol.

Warhol did not often permit himself to appear upset. The

1982 book Edie, by Jean Stein and George Plimpton, which depicted him as a

greedy voyeur in an addict’s destruction, was one such recorded case. “I never

saw him so upset about any negative press,” recalls Warhol biographer Bob

Colacello. In Basquiat, Warhol probably saw something like a redemption. “It

was clear that Andy was trying to wean Jean-Michel off drugs,” Fred Hoffman

says. “They got into this health program together, and they were exercising a

lot.” (The poster for their 1986 double show would depict the unlikely partners

mock-boxing in Everlast gloves.)

Basquiat and Warhol exchanged portraits in 1982. Later they

began to work in the Factory, making art. Their first collaborations, prompted

by Bischofberger, also involved Clemente; then the two of them carried on

without him. “Jean-Michel called me and said, Papa, I’ve got Andy with a brush

in his hand for the first time in twenty-three years,” Gérard Basquiat tells

me. Warhol, certainly, benefited hugely. “Andy felt he was getting stale. For

him, it was tremendous,” says Ethel Scull. “For Jean-Michel it was a disaster.

He got whooshed into the vacuum of Andy’s world.”

Jean-Michel sometimes bubbled with resentment: “It’s as if I

am just a protégé. As though I wasn’t famous before Andy found me.” Scull took

Basquiat to a black-tie ballet affair at which Warhol was present, and Basquiat

acted up, like a little boy: “I want to sit at Andy’s table, he demanded. Then

I found him smoking marijuana in the bar.” A longtime supporter, she began to

wonder if the painter was a goner.

On the surface, though, things were going well. Bruno

Bischofberger says that he had paid him $300,000 for some of the Warhol

collaborations and, like many Basquiat advisers, had tried to persuade him to

buy real estate. Warhol moaned to Thomas Ammann, the powerful Swiss dealer,

that Basquiat frittered away money: for instance, by renting an apartment in a

fancy hotel that he never used. “Andy said, Buy something from Thomas. He

bought a little 1922 Picasso, something a bit Constructivist.” Worried about

his junkie friends, he never took possession but would sometimes show people an

Ektachrome color slide of it.

By mutual consent, sixteen of the large Warhol collaborative

pieces were exhibited at Tony Shafrazi’s gallery. The show got lukewarm

reviews, and only one was sold. “It wasn’t seen as part of the history of art,”

a collector told me, sniffily, “but of the history of public relations.” Again

a parental relationship had failed to reach his expectations. He distanced

himself from Warhol. That summer, Basquiat left Mary Boone’s roster of artists.

It was a severe blow to him. “He had executed a number of works that had a

great energy and necessity to them,” she says. “Then he began imitating those

works. He was much too involved with the glamour, the names. He was more

involved with who was coming to his opening party than the paintings that were

going to be in the exhibition.”

Basquiat denounced Boone. His reputation among New York

dealers was dismal. Bischofberger, his only remaining dealer, granted his

“dearest wish” by organizing a show in “black Africa.” In mid-1986 he took

Basquiat and his then regular girlfriend, Jennifer Goode, now a partner in M.K.

with her brother Eric, to Abidjan. “It was Jean-Michel’s first visit to

Africa,” Goode says. “We had a wonderful time. Artists came and talked to him.

I remember he was disappointed that they were doing copies of Western art. He

thought it would be more like his work, but the only things that were anything

like his were on the outside of houses. Or just signs.” Ironically, Basquiat,

who had come to primitive art via Picasso, felt that contemporary African

artists needed liberation from the School of Paris.

He felt slighted by Warhol’s Christmas present that year—one

of his silver wigs, flattened and framed, the precursor of a line he was

planning to sell. Basquiat was so offended he withheld the Christmas card he

had made for Andy, a drawing executed in the Louvre of the Victory of

Samothrace. Although Basquiat had only turned up for five or six of his

invitations to meet since the Shafrazi show, Warhol remained the single figure

he both trusted and respected. “He was number one,” says John Good, “and that’s

what Jean-Michel wanted to be.”

Warhol died on February 22, 1987. Again, swamped by grief

and guilt, Basquiat reeled.

Basquiat had often been Bruno Bischofberger’s guest in

Europe. The dealer now introduced him to a new Manhattan gallery, Maeght

Lelong, which together with Bischofberger began paying him a monthly stipend.

But he had also grown close to another dealer, Vrej Baghoomian, Tony Shafrazi’s

cousin and former business manager, and began selling him paintings.

Basquiat signed a contract with Bischofberger nonetheless,

exchanging his share of another twenty of the Warhol collaborations for

$500,000. The contract was handwritten on a single sheet of paper, and Basquiat

later claimed that he had misunderstood it. He’d thought that he was to get all

the money at once. “But he’s trying to pay me $10,000 a month for years, and

years, and years,” Basquiat told me, bitterly. “I realized too late that I

didn’t have to sell them to him at all. He must think I’m a jerk.”

“The big ones were on sale for $200,000 to $400,000 even

before Jean-Michel died,” a rival of the Swiss dealer says. “Two of the works

pay for the whole thing. There’s a lot of elements of the Mark Rothko thing in

this. A desperate artist, who has his own psychological problems, believes that

he is being taken, but somehow still ends up in the grip of this dealer.”

Bischofberger says that he and Maeght Lelong were already owed more than

$275,000 by Basquiat in advances, and that the established practice of paying

monthly would be “better for Jean-Michel” than a lump sum. “But sometimes he

was paranoid,” says Bischofberger, whom Basquiat once drew as a wolf. “His

dealers were his friends but also his enemies.” In the fall of 1987 Baghoomian

opened a gallery “not for him, but because of him.”

The escalating desire for money was the root. When Basquiat

had money, he got rid of it, as if he was trying to purge himself. He bought a

musician friend a fishing boat. He lent a painter friend cash, and refused

repayment. By 1987, he was always running out of it himself. “He even borrowed

money from me, and I don’t have any,” says Arto Lindsay. It isn’t hard to see

why. Sales were slow. And after Warhol’s death, he started buying dangerously adulterated

heroin from street dealers. One painter who visited him for an afternoon to

discuss donations to an AIDS benefit remembers Basquiat darting out four or

five times to buy drugs, then disappearing upstairs to shoot up before resuming

the conversation. The Maeght Lelong gallery planned a big “comeback exhibition”

for the fall of 1987, but, says director Daryl Harnisch, “I saw there wasn’t

going to be anything to show. He was too drugged.” He was meant to have done

six or eight drawings for a show at Tony Shafrazi but only managed three.

The drawings and paintings that he had showered on friends

were turning up for resale. Paintings that he had sold for hundreds were

selling for tens of thousands. As his anxiety grew, so did his use of drugs. It

was now all too much for Jennifer Goode. “I went to a program,” she says, “so

did Jean-Michel. But he couldn’t go through with it.” He told friends that they

were too intrusive, they didn’t understand that he was an artist. “He had

problems with authority,” Goode says. “All those white doctors and

psychiatrists, telling him what to do. He was going to do it by himself—prove

he was stronger.” Similarly, he had rejected his father’s numerous offers to

organize his financial affairs.

There was the psychological problem, too, of not wholly

knowing the relation of the drug to his torment, and his torment to the quality

of his art. Paige Powell, another longtime girlfriend, and Warhol’s frequent

companion, heard from him after his Bruno Bischofberger opening in Zurich:

“Somebody told him his work had softened. Next thing, he was doing heroin in

Amsterdam.”

Increasingly Basquiat withdrew from the milieus he had

frequented. “I can’t relate so much to the kids that go out these days,” he

said. “All these young, perfect kids. It’s not the same sort of artistic

climate as it was back then.”

I used the word “cave.”

“Medicine men live in caves,” he said.

He wasn’t acting like a medicine man. In Basquiat’s life,

art dealers and drug dealers were now inextricably mingled—he was being given

drugs, or money for drugs, in exchange for freshly painted art. One friend

could see that the work was deteriorating. “He would just do something quickly,

and sign it—just to get them out of there.” Then he would feel terrible. “He

would talk and talk about it.”

On his rare forays out, his behavior could be fantastical.

“Last year, Jean-Michel called to invite me to Bianca Jagger’s birthday party,”

says Maggie Bult, one of the very few collectors he could abide. “We walked,

and on the way he bought every imaginable thing in the world. He bought an

enormous bubble-blowing thing from a man on the corner. He bought himself three

pairs of shoes. He bought me some lilacs to give Bianca. Everyone was looking

at him. Everybody knew just who he was.”

The party was at Nell’s. “As soon as we walked in, he became

very paranoid,” Bult says, “because his career was a bit on the wane, and he

felt he should be paid a bit more homage. He wanted more attention.” Within

five minutes, Basquiat was whisking her off for dinner at Barbetta’s. “He was

greeted very ceremoniously,” Bult says. “So we sat there, and he ordered only

the best of the best. Champagne, and baby lamb, and on, and on. Poor thing! The

bill was over $300. He loved to spend, but he shouldn’t have been spending that

sort of money.” It was almost, she feels, as if he felt guilty. On their way

out, Basquiat spoke sharply to the proprietor, Bult says. “He didn’t feel he

had been treated with enough respect.”

The horror was looking for a taxi. Bult was in a leather

skirt, and Basquiat was in a floppy black suit from Yohji Yamamoto, an open

white shirt, a straight-brimmed black hat. Not one taxi driver stopped.

“Several went by, two of the drivers were black, but nobody would take him.

Jean-Michel turned to me and said, You know why nobody is taking us? It’s

because I’m black. Can you get a taxi?” Bult swiftly got a taxi. Back at Great

Jones Street, Basquiat disappeared upstairs. “In half an hour, I called up and

said, Jean-Michel, what’s going on? Come up, he called.” Upstairs she found the

artist collapsed, and sweating heavily. “He was in a bad state,” she says. “He

began talking about Andy. He was crying. He was weeping.”

Warhol’s death precipitated a decision. When Ed Hayes, the

Warhol-estate attorney, went to Great Jones Street, he found Basquiat convinced

that they were trying to evict him. Actually, Hayes says, although Basquiat was

chronically late with the rent, he had been instructed to offer to sell him the

place at an insider price. Basquiat, he says, didn’t believe him. (Earlier, the

painter had told friends that he might raise the $350,000 purchase price by

selling his Picasso. He did sell it, but the money did not go into bricks and

mortar. He made a 50 percent profit in eighteen months, and asked Ammann for

slices of it from time to time.)

Basquiat decided his only hope was to leave New York. He had

told me he was “controlling” heroin. Now he told friends he was going to give

it up—using his mind, his will.

Basquiat went to Europe in January 1988. At his Paris

gallery, Yvon Lambert, he met an Ivory Coast painter called Outtara. Outtara, a

longtime Paris resident, thought Basquiat “un vrai bon vivant” and invited him

to his homeland. Impulsively, Basquiat agreed. In Africa, surely, he could

clean body and spirit alike.

He returned to Manhattan. Soon he, Kelly Inman, and Vrej

Baghoomian were driving around the Catskills, looking at houses. “We saw four

or five,” Inman says. “Jean-Michel put in an offer on one. He was too late. It

was sold.”

Basquiat was despondently aware of the parlous state of his

reputation. “The cheerleaders . . . are already reassessing Basquiat as a

never-was,” a columnist wrote in the spring edition of Art Line,and his

struggle with addiction continued. Frequently Inman, who had moved into the

Great Jones Street basement (they were not lovers—drugs made a relationship

impossible), would threaten to move. “Vrej would tell me, You can’t go,” she

says.

“One day he would tell me he was giving it up,” says Vincent

Gallo, “the next he’d be boasting he was doing a hundred bags a day—more than

Keith Richards.”

“I truly believed he was stopping,” says Ethel Scull. She

offered to take him to the Warhol sale in April, where there was a Twombly he

wanted as a memento. “I said, Jean-Michel, can you afford it?” remembers Scull.

He had been so desperate to get it that she was touched. “I happened to have

dinner that night with Asher Edelman,” she says. They discussed it, and the

other probable bidders. Maybe they could help him out by not bidding it up. “I

called Jean-Michel,” she says. “I told him, You’re sitting with me. We’re going

to try to let you get it.” She warned, “If you stand me up, I’ll kill you.”

Inevitably, he never showed.

“I later heard that he had gone to a jazz festival in New Orleans.”

Scull abandoned all thought of saving Jean-Michel. “I never saw him again.”

Basquiat had first flown to Hawaii during an early trip to

California, and had been there for visits ever since. He returned there this

summer. “He called me,” says Inman. “He sounded terrific. He said he was

fishing with the guys, he was giving up painting, he was going to be a writer.”

Inman joined him there at the end of June. It was less than

she had been led to expect. “He started drinking in the morning. He was drinking

all day,” she says. “He had stopped one thing, but hidden it with another.

There were art supplies out there, but he wasn’t working. He was playing music

twenty-four hours a day. He had all his jazz tapes. Charlie Parker, Billie

Holiday.” As Kelly speaks, her ambivalence is painful. “He lived the right

way—he lived every day. Most people have a lot of fear. Not Jean. He said he

was either going to die young or he would be very old—and broke, the way he

started.”

They left Hawaii at the end of June, stopping off for a day

in Los Angeles. That, at least, was the plan. “He called, and said he didn’t

have any money for a hotel,” says Matt Dike. “Could he stay for one night?”

From Dike’s, Basquiat called another old friend, filmmaker

Tamra Davis. “We went to this dinner at Mr Chow’s,” she says, “and all these

strange, strange people were there, like he’d met at the airport, a contractor

from Orange County, like it was weird, man. Just two years before we’d been at

the same table in the same restaurant with the cream of the arts community. But

Jean-Michel was in such a good mood, smiling, and jumping up and down, and

really happy, because he’d cleaned up in Hawaii, you know, not like he used to,

staring at you, kind of testing you before he would say anything, if he hadn’t

seen you for a while. It was like a guy had suddenly come back to life, but all

of a sudden I got really afraid . . . ”

Dike was also unsettled by this freaky good humor. Basquiat

announced that he was having such a terrific time— “the best time of my whole

life,” he told Tamra Davis—that he had decided to stay in Los Angeles at least

a week. “He wasn’t doing any art,” Dike says. “He was giving up. Now he was

saying he was going to start a tequila business in Hawaii. He was drinking any

kind of hard booze. He could drink a quart of tequila. It was to kill the cold

turkey, I guess.”

Tamra Davis was given the task of trying to check Basquiat

into a hotel. Not, this time, L’Ermitage. “I said, Let’s go to the Chateau

[Marmont]. He said, No, no, no. He wanted a really cheap, sleazy hotel on

Hollywood Boulevard. I was afraid of that. The drugs. We drove around for eight

hours, and he kept saying he didn’t want to drive by any neighborhoods that had

drugs. So I took him to this strange hotel called the Hotel Hollywood. With all

that he had done to himself, poking and scratching his body, he looked like

this crazy Rastafarian, he had humbled himself to such an extent. I said, You

stay in the car. You can’t even be seen with me when I try to check you into this

hotel. He looked like a bum or something.”

So she managed to sneak one of the outstanding painters of

his generation past the desk, and upstairs. There she unpacked the bag, and it

was filled with all his usual stuff, the copy of Kerouac’s The Subterraneans he

often traveled with, and two sketch pads, both abnormally empty. “I said, Why

don’t you draw? He said, No, I’m going to become a writer. I want to become a

writer. But I can’t write. . . . ”

She left, filled with forebodings. Over the next few days,

she saw him continuously. There happened to be a painting by Basquiat at

Dike’s, a self-portrait executed a couple of years previously on an old door.

It showed the artist, missing a front tooth, with his body as a skeleton. He

was now actually missing a front tooth—he said it had just dropped out in

Hawaii. “He looked at the bones,” Dike says. “He said, I hope that doesn’t come

true, too.”

One night he and Davis drove up to the Country Store on

Laurel Canyon Boulevard. Basquiat was uproariously drunk, and in an excellent

mood. “He’s sitting there with the door wide open, drinking tequila mixed with

Corona, and yelling to everybody that would pull up—in a friendly way, but

these people were looking at him as if he was totally crazy. Then he would get

very sentimental, and want to talk about himself, really heavy things about his

childhood, how he’s going to stop painting, what’s going to happen to him.

K/Earth 101 was playing. There was this Firecracker 300 countdown. I was

telling him to stay up and listen to the winner so he could tell me the

number-one song. Because I knew it would be in the middle of the night. And I

was afraid he would die before that, even.”

One of the songs they listened to was Elton John’s lament

for Marilyn Monroe, “Candle in the Wind.” “He said, That’s me,” Tamra Davis

says. “I’m not a real person. I’m a legend.”

His apprehensions, once he was back in New York, seemed to

fade. “I saw him on the street,” Haring says. “It was the first time I had seen

him in a whole while. He was really up. He told me he had kicked. Which is the

first time he had even acknowledged a habit at all. He seemed honestly

excited.”

Haring, who had an assignment to photograph street fashion,

was carrying a camera, and Basquiat insisted on posing. Haring shot him, laid

out on a subway grating on Lower Broadway. “It’s almost too weird,” Haring

says. “In a lot of them he’s got his eyes closed.”

He spoke to Vincent Gallo about getting back into music. “It

was as if art wasn’t part of him anymore,” Gallo says. Arto Lindsay recalls

that Basquiat played some tapes to him and John Lurie of the Lounge Lizards:

“murky-sounding tapes that didn’t go anywhere, outer-space-type things.”

The Palladium was redecorating the Mike Todd room and

Basquiat told me he had offered to sell them his two paintings there for

$50,000 each. Steve Rubell had declined. They were delivered back to the

artist. “They’re O.K.,” he said, “except for a few holes and ballpoint-pen

marks.” He returned to Hawaii for another couple of weeks, and again stopped in

Los Angeles on his way back. “He must have called a million times,” Tamra Davis

says. “I feel so guilty I never answered. How could I invite that drama back

into my life?”

Gérard Basquiat says that his son had a flight booked to

Abidjan on Sunday, August 7, but he didn’t arrive in New York until Monday. He

rescheduled for Thursday, August 18. Outtara was there, waiting. “We were going

to go to my village,” Outtara says. The plan was that he’d stay there for three

months, painting with “natural materials,” curing himself. “Everything was

ready for Jean-Michel. Everything was done,” Outtara says.

Kelly Inman returned from a trip home to the Midwest on

Wednesday, and was appalled by Basquiat’s beer bloat. His sister Lisane called

him on the morning of Thursday, August 11. He was curt. “I was angry when I

hung up,” she says. “I discussed it with my mother. I said, How can he still

keep all that pain in him?”

That was at about half past ten in the morning. There are

rumors that Basquiat bought drugs that day. His father confirms that

substantial quantities were found in the bedroom.

Kristen Vigard was passing Basquiat’s front door at about

half past six. She hadn’t seen him for some time, but impulsively she knocked.

“He took two of my friends to Hawaii. A boyfriend of mine, and a girl. They had

drug problems. He cleaned them up. I thought he was a saint.”

Basquiat was overjoyed to see her, but she was shocked to

find him high, and rambling. “I didn’t know what to say,” she says. “I read him

a poem against drugs I had written.” Kelly Inman arrived, and they sat around

drinking Coco Rico. Then Vigard went out to the store to get Basquiat some

supplies. Jay Shriver, Warhol’s former painting assistant, came over at 7:30.

“He told me that he was giving up drugs,” Shriver says. “He said he was just

bingeing a little.”

Shriver departed. “I don’t know how Jean-Michel got out of

there,” he says. “He could hardly walk.” Vigard and Inman, now both thoroughly

alarmed, determined to get Basquiat on his feet. “Come to the Bryan Ferry

party,” Vigard implored. They coaxed Basquiat to M.K. There they lost him.

It might be said that Basquiat died of many things. His body

was terribly weakened—that missing spleen. Also that missing tooth—which fueled

the rumors Peter Schjeldahl cited in his 7 Days obituary that the artist had

AIDS. Junkies, however, tell me that their teeth often go (the sugar diet, the

acid in the vomit). And one close friend says he saw a bag with a shiny, deadly

load of needles in Basquiat’s bedroom—so forget shared syringes: “He probably

changed the works every time he shot up.”

The morning after the day on which Basquiat died, Inman, who

was still in a state of stunned calm, was telephoned by one of Basquiat’s “old

friends.” He perfunctorily expressed his regrets. “Then he said he’d left

something in the studio, a painting, a drawing, and could he come around and

collect it.” Inman said no. “I would have flipped if I had seen him,” she says.

“Now there’s a guard outside. The place is locked up tighter than a drum.”

Thus, the rapacity that plagued the artist in life pursues

him still. “Vultures,” says Bischofberger. Even close friends of Basquiat’s

that I spoke to would often get around to asking how his death would affect the

value of the works. Thaddaeus Ropac, a Salzburg dealer who had put on

Basquiat’s final show, ending on August 10, two days before the artist’s death,

immediately bought back an important painting at double the price he’d sold it

for. “I hadn’t even been paid yet,” he says. Basquiat talked of having a great

deal of his work salted away in storage around New York. Michael Stout (also

attorney for Dali and Mapplethorpe) speaks of four possible stores, one with

“one hundred works” and another with twenty-five, also “one hundred on canvas at

Great Jones Street, and hundreds of drawings,” plus “works out on consignment

that we would have claims for.” It would be hard to estimate the total value of

all this, probably in the tens of millions, but Vrej Baghoomian says he’s only

aware of a dozen salable canvases in the studio. Paige Powell, among others,

disagrees: “Andy told him to keep his best paintings. He made it cool for him

to be a businessman and an artist.” Anyway, Christie’s is cataloguing, and in

mid-November the Mayor Gallery in London will be showing, seventeen of the

Warhol-Basquiat collaborations, priced at $300,000 a piece.

At the time of writing, no will has surfaced, so Gérard

Basquiat is administering the estate. There is, however, the persistent rumor

of a child. Basquiat told friends of a son in New Orleans called Noah, who

would now be five. Though one source doubts that Jean-Michel was the father.

That said, Basquiat’s bitterly ironic cliché of a death—the

young black on dope belongs with the drunken Indian, the thrifty Scot—will

surely focus attention where it actually belongs, on his work, some of the best

of which was never hung in his relatively few shows. “They were taken straight

out of his studio,” says Jeffrey Deitch. “They were never catalogued. Some of

the most incredible work went straight to Europe. The art world never got a

chance to see them.” Much of this can now be expected to change. “I suppose

he’ll get a Whitney show at last,” says Fred Brathwaite. “And all that shit he

never got when he was alive. Motherfuckers!”

Three years before, on a Hawaiian holiday, Gérard Basquiat

had asked his son why he was so “tense.” “You’ve got everything,” he had told

him. “Only one thing worries me,” his son had said. “Longevity.” He had meant

as an artist, not as a man. Some, including Larry Gagosian, feel that Basquiat

was facing “a block.” Others feel his work was constantly getting stronger. It

is now unknowable, as it cannot be known how seriously to take his plan of

abandoning art, Rimbaud-like. “The body of work is phenomenal,” says Tony

Shafrazi. “The guy produced maybe five to six hundred major canvases in about

eight years. He was the epitome of the romantic artist—literally living the

dark side of Van Gogh.”

Which is not to say that Basquiat’s death should be read as

a pat conclusion. “Everybody was sitting around, waiting for him to do what he

did,” says Glenn O’Brien, “so he could be the Jimi Hendrix of art. He burned

out his body, I guess. But I don’t think he intended to die—I think he could

have recovered.” In September, O’Brien and I passed Basquiat’s scarred metal

front door. Somebody had made a shrine of wickerwork and hung it on the

adjoining wall. A photograph of Basquiat, from the poster for his last show,

was framed with flowers, candles, handwritten love letters, and a couple of

brushes, one dipped in gold. “Voodoo, voodoo,” a passerby told us, cheerily.

Jean-Michel Basquiat would have liked that.

Comments