A Real Foreign Policy

What

is "foreign policy?" Does it simply refer to the relationships between

nations? The policy frameworks through which some are treated as allies

and others as enemies? Does it deal with the level of respect or trust

that other nations are afforded? Foreign Policy is one of those elements

that the media and the educated classes act like is critically

important in terms of electing leaders. It is something that those more

serious segments of society use to argue for the electability of certain

candidates, such as Sarah Palin, Donald Trump or even George W. Bush.

The sectors feel compelled to remind the American people as a whole

about the seriousness of picking someone who does not only look within

to serving the nation, but can also be relied upon to engage with the

rest of the world. After all, no matter how large your country thinks it

it, even if it is massive in terms of economy, population or land mass,

the rest of the world remains. A country's foreign policy, despite the

rhetoric with regards to it being about engagement, is often times just

an exercise in reducing the rest of the world to being effects of your

nation's interests, to the point where their existence is all determined

by your place and desired place in the world, and little to do with

what they might want or need.

What is ironic is that "foreign policy" has so little to do with anything foreign. The larger the country, the more foreign policy is about taking everyone around you and making them an effect of you. Making it so that they fit within your vision of the world, what type of order there should be. For a larger country, there is nothing earnest about it, but rather it becomes a way of redefining imperialism and colonialism until it appears to be much less odious and far more normalized.

But what would foreign policy look like, if it abandoned such ambitions? And it respected the rights of other nations, to be different, to have their own interests? This article has some ideas.

******************

What is ironic is that "foreign policy" has so little to do with anything foreign. The larger the country, the more foreign policy is about taking everyone around you and making them an effect of you. Making it so that they fit within your vision of the world, what type of order there should be. For a larger country, there is nothing earnest about it, but rather it becomes a way of redefining imperialism and colonialism until it appears to be much less odious and far more normalized.

But what would foreign policy look like, if it abandoned such ambitions? And it respected the rights of other nations, to be different, to have their own interests? This article has some ideas.

******************

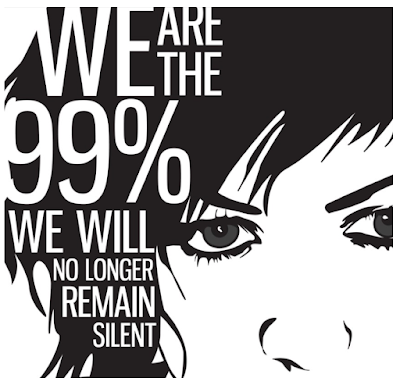

Towards a Foreign Policy for the 99 Percent

Relief,

rather than elation, was probably the emotion most U.S. peace activists

felt when President Barack Obama won re-election. While Obama has been

very disappointing on most peace issues, Mitt Romney would have been all the worse. So what now to expect from a second Obama term?

Most likely, more of the same; anyone expecting Obama to be decidedly more pro-peace this time around is likely to be sorely dispirited. However, there is a diverse, growing peoples’ movement in the United States linking human and environmental needs with a demand to end our wars and liberate the vast resources they consume. This, combined with budgetary pressures that should dictate at least modest cuts in the gargantuan Pentagon budget, could lead to serious constraints on new militaristic ventures such as an attack on Iran, “modernization” of the entire U.S. nuclear weapons enterprise at a cost of over $200 billion, a permanent U.S. force of up to 25,000 troops in Afghanistan after 2014, or an absurd military “pivot” toward the Asia-Pacific aimed at isolating Russia and especially China.

We in the peace movement need to be able to think, and act, with both a short- and long-term perspective. In the near term, swiftly ending the war in Afghanistan and ensuring no long-term U.S./NATO troop presence, stopping drone strikes, preventing a war with Iran and building support for a WMD-free zone in the Middle East, pushing for serious cuts to the Pentagon budget, and advocating progress toward nuclear disarmament will consume most of our energies. Renewed emphasis on a just and lasting peace between Palestine and Israel should also garner more attention and activism. Finally, peace activists will need to lend solidarity those working to save social programs from austerity-minded elites and to address climate chaos.

In the longer term, we need to hasten what Professor Johann Galtung calls “The Decline of the U.S. Empire and the Flowering of the U.S. Republic.” We have an opportunity in opposing the outrageous “Asia-Pacific Pivot,” which the military-industrial complex has concocted without asking the American people if we support it or want to continue borrowing from China to pay for it (too weird, right?). We can point out the insanity of this policy, but we can also devise a better alternative, including building solidarity with the peoples of Okinawa, Jeju Island, Guam, the Philippines, Hawaii, and other nations in the region opposing the spread of U.S. militarism and advocating peaceful relations with China.

Defining the Democratic Deficit

This pivot is just the latest example of the fundamentally undemocratic nature of U.S. foreign policy.

The more we in the peace movement can point out that our tax dollars fund policies contrary to our interests, the easier it will be not just to build specific campaigns for more peaceful and just policies, but also to create a new vision for our country’s role in the world—to create a new foreign policy for the 99 percent.

So we peace activists need to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time. We need to offer credible, sustainable alternatives on the issues listed above, with specific actions ordinary people can take that make a difference. But we must go further and advocate a foreign and military policy that is in the interest of the majority of this country, one that comports with widely shared ideals of democracy, justice, human rights, international cooperation, and sustainability.

It’s no news flash that elite and corporate interests have long dominated U.S. foreign policy. Illustrating this democratic deficit has two related aspects. The first is the question of access: “he who pays the piper calls the tune.” Currently, although it technically foots the bill, Congress—let alone the public—has barely any say in how U.S. foreign policy is set or implemented. On a second and integrally related note, in whose interest is it to perpetuate a gargantuan military budget, maintain a vast and expensive nuclear arsenal, or start an arms race with our banker, China? It’s hard to imagine that any ordinary person could conclude these policies serve anyone but the 1 percent.

Notions of justice and human rights are widely resonant in the United States, but they require careful consideration and explanation. “Justice” should not be invoked simply as it concerns parties to a conflict, but rather should entail racial, social, and economic fairness for all those who are affected by the grinding military machine. Emphasizing the broader social consequences of militarism will be key for growing our ranks, especially among people of color, community activists, and human needs groups. And while “human rights” is a no-brainer, it requires courage and commitment to communicate how U.S. foreign policy constantly contradicts this ideal abroad, even as our government selectively preaches to other countries on the subject.

International cooperation, while it can seem vague or milquetoast—especially given the neglect or outright stifling of “global governance” structures by the United States—is a highly shared value among people in this country and around the world. Selling cooperation as a meaningful value is fundamentally important for undermining the myth of American exceptionalism, which so many politicians peddle to sell policies that only harm our country in the long run.

Finally, while the environmental movement still has loads of work to do, the successful promulgation of the concept of sustainability is an important achievement, one we can easily adapt to military spending, the overall economy, and a longer-term view of what kind of foreign policy would be sustainable and in the interest of the 99 percent. Climate activists and peace activists need to know that they have a vital stake in each other’s work.

A glimpse of the power of democracy was in evidence on Election Day, and not just in the legalization of gay marriage and recreational marijuana in a few states. When given a choice, as in referenda in Massachusetts and New Haven, Connecticut advocating slashing military spending and funding human needs, people will choose the right policies and priorities; both initiatives won overwhelmingly.

Contrary to the hopes many people in this country and around the world invested in Barack Obama (which he didn’t deserve and frankly he never asked for), it’s never been about him. It’s about the entrenched power of the U.S. war machine, and about how we the peoples of this country and around the world can work together to create more peaceful, just, and sustainable policies. We can do it; in fact we have no choice but to do it.

Most likely, more of the same; anyone expecting Obama to be decidedly more pro-peace this time around is likely to be sorely dispirited. However, there is a diverse, growing peoples’ movement in the United States linking human and environmental needs with a demand to end our wars and liberate the vast resources they consume. This, combined with budgetary pressures that should dictate at least modest cuts in the gargantuan Pentagon budget, could lead to serious constraints on new militaristic ventures such as an attack on Iran, “modernization” of the entire U.S. nuclear weapons enterprise at a cost of over $200 billion, a permanent U.S. force of up to 25,000 troops in Afghanistan after 2014, or an absurd military “pivot” toward the Asia-Pacific aimed at isolating Russia and especially China.

We in the peace movement need to be able to think, and act, with both a short- and long-term perspective. In the near term, swiftly ending the war in Afghanistan and ensuring no long-term U.S./NATO troop presence, stopping drone strikes, preventing a war with Iran and building support for a WMD-free zone in the Middle East, pushing for serious cuts to the Pentagon budget, and advocating progress toward nuclear disarmament will consume most of our energies. Renewed emphasis on a just and lasting peace between Palestine and Israel should also garner more attention and activism. Finally, peace activists will need to lend solidarity those working to save social programs from austerity-minded elites and to address climate chaos.

In the longer term, we need to hasten what Professor Johann Galtung calls “The Decline of the U.S. Empire and the Flowering of the U.S. Republic.” We have an opportunity in opposing the outrageous “Asia-Pacific Pivot,” which the military-industrial complex has concocted without asking the American people if we support it or want to continue borrowing from China to pay for it (too weird, right?). We can point out the insanity of this policy, but we can also devise a better alternative, including building solidarity with the peoples of Okinawa, Jeju Island, Guam, the Philippines, Hawaii, and other nations in the region opposing the spread of U.S. militarism and advocating peaceful relations with China.

Defining the Democratic Deficit

This pivot is just the latest example of the fundamentally undemocratic nature of U.S. foreign policy.

The more we in the peace movement can point out that our tax dollars fund policies contrary to our interests, the easier it will be not just to build specific campaigns for more peaceful and just policies, but also to create a new vision for our country’s role in the world—to create a new foreign policy for the 99 percent.

So we peace activists need to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time. We need to offer credible, sustainable alternatives on the issues listed above, with specific actions ordinary people can take that make a difference. But we must go further and advocate a foreign and military policy that is in the interest of the majority of this country, one that comports with widely shared ideals of democracy, justice, human rights, international cooperation, and sustainability.

It’s no news flash that elite and corporate interests have long dominated U.S. foreign policy. Illustrating this democratic deficit has two related aspects. The first is the question of access: “he who pays the piper calls the tune.” Currently, although it technically foots the bill, Congress—let alone the public—has barely any say in how U.S. foreign policy is set or implemented. On a second and integrally related note, in whose interest is it to perpetuate a gargantuan military budget, maintain a vast and expensive nuclear arsenal, or start an arms race with our banker, China? It’s hard to imagine that any ordinary person could conclude these policies serve anyone but the 1 percent.

Notions of justice and human rights are widely resonant in the United States, but they require careful consideration and explanation. “Justice” should not be invoked simply as it concerns parties to a conflict, but rather should entail racial, social, and economic fairness for all those who are affected by the grinding military machine. Emphasizing the broader social consequences of militarism will be key for growing our ranks, especially among people of color, community activists, and human needs groups. And while “human rights” is a no-brainer, it requires courage and commitment to communicate how U.S. foreign policy constantly contradicts this ideal abroad, even as our government selectively preaches to other countries on the subject.

International cooperation, while it can seem vague or milquetoast—especially given the neglect or outright stifling of “global governance” structures by the United States—is a highly shared value among people in this country and around the world. Selling cooperation as a meaningful value is fundamentally important for undermining the myth of American exceptionalism, which so many politicians peddle to sell policies that only harm our country in the long run.

Finally, while the environmental movement still has loads of work to do, the successful promulgation of the concept of sustainability is an important achievement, one we can easily adapt to military spending, the overall economy, and a longer-term view of what kind of foreign policy would be sustainable and in the interest of the 99 percent. Climate activists and peace activists need to know that they have a vital stake in each other’s work.

A glimpse of the power of democracy was in evidence on Election Day, and not just in the legalization of gay marriage and recreational marijuana in a few states. When given a choice, as in referenda in Massachusetts and New Haven, Connecticut advocating slashing military spending and funding human needs, people will choose the right policies and priorities; both initiatives won overwhelmingly.

Contrary to the hopes many people in this country and around the world invested in Barack Obama (which he didn’t deserve and frankly he never asked for), it’s never been about him. It’s about the entrenched power of the U.S. war machine, and about how we the peoples of this country and around the world can work together to create more peaceful, just, and sustainable policies. We can do it; in fact we have no choice but to do it.

© 2012 Foreign Policy in Focus

Comments