Vampire Hunter Z

Ever since purchasing Vampire Hunter D and Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust, from Ebay, I’ve been mulling over this post.

After watching them years ago and enjoying them very much, I re-rented them from Blockbuster and decided to see what a difference a few years, several dozen books on psychoanalysis and poststructuralist theory and vanquishing both runs of Cowboy Bopeep/ Cowboy Bebop and Evangelion: Neon Genesis would make.

It made a very interesting difference.

First of all, I became convinced after watching the trials, struggles and victories of D, that the figure of the lone, isolated bounty hunter is ideal for discussing the type of Lacanian lone-wolf, assassin/mercenary psychoanalysis that Zizek espouses.

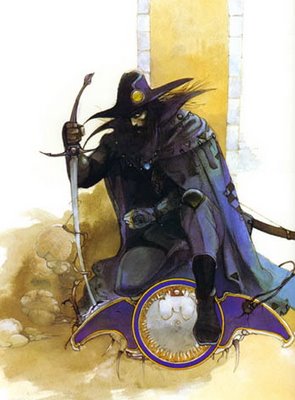

For those of you unfamiliar with the anime, D is a dunpeal or damphir, a half human/half vampire, who works as a vampire hunter for hire. In this world, much of humanity as been destroyed by nuclear war, and vampires have become the world’s new rulers or “aristocracy” as they are referred to in the first film.

Since, its hot as I’m writing this, with no aircon, and I’m on Guam, and my posting abilities have been severely comprised since I came home, let me just list in almost bullet form (rather than sleek narrative form), the connections I’ve made between Zizek’s style of political psychoanalysis and the film world of Vampire Hunter D.

1. Salape’

D hates vampires, almost more than the humans that they prey upon. This hatred, we assume would almost certainly lead him to do some pro bono work and slaughtering these fiends, or possibly, just be a non-profit entity and just roam the earth killing them. This is however not the case, as in the films D consistently seeks some sort of payment for his hunts, in particular in the second film, where upon being hired to find the daughter of a prominent family, he demands an exorbitant amount to kill her (humanely) if she has already been turned.

Why?

The reason that D demands money is no doubt similar to the psychoanalyst’s demand for money, for some sort of payment prior to analysis taking place. There is no such thing as “psychoanalysis amongst friends,” the work of the psychoanalysis demands not objectivity, but distance and disinterest, in order to force the patient to do the work.

There is a joke that I think is attributed to Jacques Alain Miller, that under capitalism the capitalist pays the worker to do the work in place of himself. Under psychoanalysis, the patient pays to the psychoanalysis to do the work himself. While this joke might seem a stretch in terms of its relevance to the general notion of a bounty hunter, this is hardly the case, in particular with D.

Money therefore functions as something far more then simple practical exchange and purchasing power. It acts as a buffer, allowing the often harsh and brutal work of psychoanalysis to be accomplished. The huge sum of money that D demands in Bloodlust, is precisely what allows him to keep his distance from all parties involved, the father and brother as well as the girl who has been taken by the vampire. It is a necessary formality that allows the necessary killing to take place.

The split task that D is given in Bloodlust clues us into the desired and demanded jobs of the analyst. The patient often goes into psychoanalysis with the desired intention of preservation or conversation. There is a problem, a tick, a nag, a recurring/disturbing fantasy or dream, the patient wants relief from it, but is never willing to resolve the trauma or the unconscious/guilty pleasure that creates that problem. The patient comes to the analyst with the same intentions as the father and brother in Bloodlust, we have a problem, we want to solved, but nothing must be destroyed in the process. Fix it, but get rid of nothing! Or in the words of the film, “just bring her back!”

The demand for more money, beyond what the patient seemed willing to pay at first, and the forcing of a recognition of the tainting of this pleasure, this thing to be conserved begins the psychoanalytic process. In order to bring about the psychoanalytic cure, something must die. Something must be lost in order for a new dynamic to emerge, a new symptom, a new neurosis, etc. The money that D demands while obviously part of the unsettling of the defenses of those hiring him, is just as much for himself, a reductive act, which creates the buffer against any seductive defenses or any weakness in feeling a need to identify with the pleasure of the client. A somewhat sadistic gesture through which both the analyst and the patient can kill the attachment, can kill the source of “wicked” joissance.

2. Famalao’an

This of course leads to a necessary discussion of the poorly feminist and occasionally anti-feminist tone of Zizek and Lacan’s work, which we find in D’s swearing off of all women a

When reading Zizek’s texts, such as his essays in Metastases of Enjoyment, one cannot help but be reminded of the most lurid detail of Laura Joh Rowland’s character Sano Ichiro and his detective adventures in 17th century Japan, namely “manly love.” The forsaking of women because of their potential for distraction and wrong turns on the path of bushido.

We find this point very interestingly and almost unnoticeably foreshadowed and put to use in the Russian film Nightwatch. In the film beginning which lays down the history and mythology of the light and dark worlds and their constant policing and manipulating of each other, the primitive theme of “female pollution” is invoked to explain the nature of the divided worlds. (Adahi sa’ ti apmam spoilers magi) Later in the film, we find that the entire plot involving the female character the nightwatch has been desperate to find means nothing and has just been a distraction from the apocalypticaly important plot which has been slowly trudging along in the background.

Don’t take my points though as if I’m some noob theorist (ti to’a na theorist) who has reduced the entire body of work from Lacan to “sexist” and will have nothing more to do with that particular French Philosopher, until his ecrits which are much nicer to women are published. The work of the Slovenian School of (Lacanian) Psychoanalysis has produced an number of confusing but extremely interesting discussions about feminism and subjectivity, and while I have read a few of these texts I don’t feel as though I can decently discuss them. (For example, what changes in our interpretation if we think of the Count’s daughter from the first film, or the female bounty hunters in the second film, in terms of Copjec’s theories on non-phallic joissance?)

Since I cannot continue very well with that conversation, this point will have to remain at the sad level of, “Atan Si Zizek! Sigi ha’ manguentos baba gui’ put famalao’an!”

3. I Tinaya’

The Void and the Infinite.

One of the most interesting characters of Vampire Hunter D is the nameless creature that lives in D’s hand. For those who haven’t seen this thing it is pretty interesting. On one of D’s hands there is a face, which talks, gives D advice and regularly criticizes him, which also gives him incredible power because of the apparent void it has access to. Throughout the anime D commands this creature to suck in and dispel different things, which are taken into the palm of D’s hand and disappear regardless of their size, into the void within.

For those familiar with Zizek’s latest obsession with the Act and the void, as well as Badiou and his notion of ethics from Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil, this creature should evoke clear parallels. Badiou’s heavily Lacanian laden definition of ethics is precisely this creature of D’s, a link whereby the human encounters the infinite, immortal void beyond itself and does not shriek in terror and retreat into the careful flesh of the human, but instead rides that drive and piercing freedom that it represents.

A paper that I’m working on and have mentioned briefly on this blog will make this point more clear. The contemporary giants of bristling ethics tend to be Samurai figures, such as Ogami Itto from Lone Wolf and Cub, who constantly lectures EVERYONE around him as to the finer points of EVERYTHING. But in the process of doing so constantly defends the link between the human and the inhuman. Or in other words, when Ogami Itto and Retsudo Yagu constantly piss on the fears of peasants, the weakness of normal non-bushido people, they are providing an ethical statement, an interpretation, but in doing so, stand as the guard preventing the human from touching the inhuman. As the samurai is supposedly the soul, the drive which can continue to kill its enemy even after being decapitated or mortally wounded, it therefore straddles the line between the mortality of human life, driven by pain and pleasure, and the world of inhuman, immortal drives, and defends the world beyond, and drives off (like kanjo) all those who would dare to taste the world of the death drive.

To bring a bit of Deleuze and Guattari into the mix, the samurai in Ogami Itto clearly defends something. He will name it, he will explain it, and often times he makes other samurai cry because of his seemingly undifferentiated fidelity to it. True ethics however touches the world beyond the human, which means that despite the chaos, the revolution that can come about because of the moment, it will always appear as a fidelity, a defense of nothing. It is for this reason that despite Ogami Itto’s (and those positioned like him) status as the uber-ethical hero, because of his death drive like persistence, he nonetheless embodies a clearly conservative ethics. For me, and this is the meat of the paper I’m working on, character such as Toshiro Mifune’s Sanjuro (or Yojimbo) or even Spike from Cowboy Bopeep/ Cowboy Bebop better embody a revolutionary taste of ethics.

For example, when Ogami Itto is faced with the abyss of human freedom, the void at the center of the symbolic world which is replicated at the center of himself, he clings to the code of the samurai to keep the raw intensity of these (non) worlds of drives at bay. He therefore prevents any revolutionary ethics from taking place, and truly dies in the final issue of the manga. In contrast to this, Spike throughout the single season of Cowboy Bopeep makes few attempts to rebuff the drive he finds in the void, he makes few attempts to describe it or contain it. Instead he finds himself pulled by it, pushed by it, and follows it until his death in the season’s last episode. But as I posted several months ago, it is precisely his last ethical act, which allows a different dynamic to persist in when the film is made. The fidelity to this impossible drive, to be tainted by its festering immortality is the means to radically alter the structure of the symbolic world, to “re-quilt” it as Zizek describes.

It for this reason that D becomes a sort of Man in Black, in the vein of Johnny Cash’s song, both literally and theoretically.

5. I Daggao

Zizek often quotes the following statement from Parsifal and I in turn have

often quoted him quoting it. “The Wound Can Only Be Healed by the Spear that Caused It.” “Siña mana’homlo I chetnot ni’ i se’se ni’ muna’dano’’” My relationship to this quote changes often, sometimes I agree with it, other times, I feel it gives modernity far too much credit.

The context for the quote is the Marxist conditions for the dissolution of Capital. The revolution of Capital is that there is no longer any outside to it, because of the nature of its deterritorialization and reterritorialization, nothing outside can truly stand against it. It can only be resisted and dissolved therefore, from the excesses that it creates as it rumbles on scorching the planet. So in the most simplistic way possible, Marx’s solution to the anti-humanism of capitalism is not indigenous communities, luddites, or people who have tried to dodge or evade the horrors of capitalism, but instead precisely the thing that capitalism creates and holds at its core, the exploited working classes.

The basic point being that a system through its excesses will create the means for its very destruction.

We see this point made with the creation of D himself, born of an unnatural union with someone who might be the Vampire King and a human woman. In the first film through debates between Count Lee and his daughter, we are informed that these sorts of unions do embody an weakening excess on the side of the nobles. The Count who has lived for thousands of years, grows weary of his own kind and every once in a while takes a human for his bride. Interestingly enough, at the film’s end it is the product of one such unholy union that kills the invincible Count, D. (this fact is further accentuated by Lee’s lackey’s attempt to use the lamp to disarm and disable his boss, which in contrast to the successful hybrid fighting of D, fails miserably).

5. Finakpo’

Some weak, scattered but still somewhat interesting points.

My last point is a bit of a pun. Is it finally so perfectly apt in a reversible way (Zizek’s style), na i psychoanalyst i mediku ni’ muna’fanhohomlo (na’magom i hinasso) taotao siha ni’ i fino’ (palabras, sinangan), ya Si D, guiya muna’fanhomlo’ i tano’ (ginnen i vampires) ni’ didide’ na fino’.

Comments