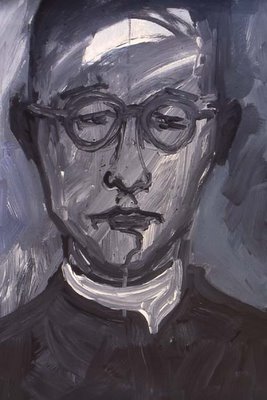

Pale' Duenas

Another painting I did of Pale' Jesus Baza Duenas.

Another painting I did of Pale' Jesus Baza Duenas.A big part of the 4th chapter of my Micronesian Studies Master's Thesis was a "repositioning" of this particular Pale' and challenging dominant representations of him as an American patriot, by showning how manamko' discourse often went back and forth over why exactly he fought against the Japanese so fiercely. For some it was because he was an American patriot, for others it was because of his Catholic faith, and thankfully for others it was his commitment to his people.

My problem with the primary ways that Pale' Duenas is remembered and understood is that they seem to have nothing to do with him, but are instead always derived from a skeletal outline of his life which was endlessly reproduced after World War II. During my interviews for my thesis, even people who knew otherwise would often end up repeating the same facts, almost on cue, and it would take some prodding and pushing over hours sometimes to make them refer to something else. People who had incredible stories about Pale' Duenas would for some reason merely reiterate the publicly approved points a thousand times before mentioning anything else. But this has happened with nearly all Chamorros and their World War II experiences. When something becomes far larger then themselves, they tend to think that their experiences have no impact, effect, meaning, especially if they conflict with that larger thing. The details of their lives must therefore conform to whatever form this now overwhelming and hegemonic thing takes. Throughout my interviews I found hundreds of false memories, of people who were changing their lives in order to conform to the established narratives of the war. People left out their anger towards the United States, their feelings of betrayal, ways they were abused or mistreated by Americans and would instead structure their feelings based on some public figure attached to how the war is to be told.

The late Pedang Cruz for example had such an effect. When he was elevated as a hero amongst the Insular Guard for fighting the Japanese in 1941, his story became the thing which all the other Insular Guardsmen would have to match their own experiences against. So despite the fact that many Insular Guardsmen did not fight against the Japanese, but instead chose to run rather than fight and die for their colonizer, these narratives are either carefully hidden or completely unknown. Instead, a network of stories which are careful not to deform that dominant narrative emerge, which are often times not the stories of these men, but re-written versions of Pedang Cruz's tale.

We see this dynamic across the war's historical landscape. Where people constantly find ways of re-shaping themselves in order to be written into those powerful narratives and moments. Why this need? One way of answering this is to look at the potential consequences of bad or low fidelity. Refusal to adhere to these dominant narratives can mean being stricken with social psychosis, or becoming one of those people who is alive yet not seen as being able to speak. Not coherent, not rational, and therefore is always cursed with screaming in silence. No one can hear you, because no one needs to hear you, you have nothing to say.

Comments

peace.

lola