Mensahi Ginen i Gehilo' #23: Commonwealth Memories

Commonwealth is a word that continues to haunt discussions of decolonization in Guam.

For most younger people, they have no idea what Commonwealth means in a Guam context, although they know of it in the context of the CNMI's political status.

It is something that has some very profound meanings for people of a certain age, most older than I am, because of the way it represents nostalgia for a time when political status change on Guam seemed to have a more clearly defined direction.

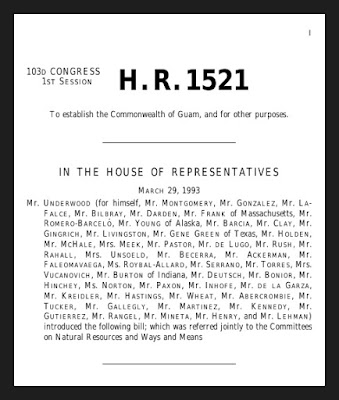

Commonwealth in terms of Guam, was a decades long movement to try to get the island to a new political status, something along the lines of "improved status quo."

It involved long negotiations with different presidential administrations, different iterations of Congress, all in the hopes of moving Guam to a slightly better political position.

In terms of political status options, Commonwealth would fall between integration and free association. It kept Guam and the US tightly connected, but also could have given Guam some autonomy, similar to that the CNMI had initially negotiated.

But the movement failed and in 1997 a Commonwealth Bill for Guam died in the US Congress.

In today's discursive spaces and debates, Commonwealth is invoked as some nostalgia for a less risky option for Guam's future.

When someone doesn't know much about the three available options, or finds the ones offered to be unsavory, that person, if they know the term or even just a sliver of the context, may wonder aloud, "What ever happened to Commonwealth? Isn't that supposed to be an option?"

I have conversations about this every week, and just finished one earlier today.

I decided to dig up a few articles from the Commonwealth era, just for those who want to know more about it.

In a future post I'll detail more about why Commonwealth isn't necessarily something that we should pursue.

*********************

For most younger people, they have no idea what Commonwealth means in a Guam context, although they know of it in the context of the CNMI's political status.

It is something that has some very profound meanings for people of a certain age, most older than I am, because of the way it represents nostalgia for a time when political status change on Guam seemed to have a more clearly defined direction.

Commonwealth in terms of Guam, was a decades long movement to try to get the island to a new political status, something along the lines of "improved status quo."

It involved long negotiations with different presidential administrations, different iterations of Congress, all in the hopes of moving Guam to a slightly better political position.

In terms of political status options, Commonwealth would fall between integration and free association. It kept Guam and the US tightly connected, but also could have given Guam some autonomy, similar to that the CNMI had initially negotiated.

But the movement failed and in 1997 a Commonwealth Bill for Guam died in the US Congress.

In today's discursive spaces and debates, Commonwealth is invoked as some nostalgia for a less risky option for Guam's future.

When someone doesn't know much about the three available options, or finds the ones offered to be unsavory, that person, if they know the term or even just a sliver of the context, may wonder aloud, "What ever happened to Commonwealth? Isn't that supposed to be an option?"

I have conversations about this every week, and just finished one earlier today.

I decided to dig up a few articles from the Commonwealth era, just for those who want to know more about it.

In a future post I'll detail more about why Commonwealth isn't necessarily something that we should pursue.

*********************

Immigration and trade are the areas expected

to be most affected if Guam is successful in its push to become a

commonwealth of the United States.

For almost 100 years, the island has been ruled by the United States, most recently as a non-self-governing territory.

In

1987, the Chamorro people, who comprise the indigenous population of

Guam, passed the Guam Commonwealth Act, which requests the policy

change. It has been a periodic subject of hearings in Congress.

The

act's most significant feature is it would give Guam complete control

over immigration laws, allowing the island to have access to laborers

and issue Guam-only visas to promote tourism.

Businesspeople

interviewed liked the idea of Guam controlling its own borders and said

it was a key element in the governor's Vision 2001 plan, which aims to

increase tourist arrivals to about 2 million by the year 2001. The

island now welcomes about 1.3 million visitors a year.

"The

governor ought to make those kinds of decisions," said Bob Coe,

regional president for DFS Group LP. "We're going to have a need to

expand the work force and the governor doesn't have that capability."

The 1990 census reported 20,000 aliens lived on the island and an additional 16,000 people were naturalized citizens.

Hoteliers

said although the isle's unemployment rate hovers at 9 percent, filling

jobs with qualified workers is difficult, especially since developers

are rapidly opening new resorts.

Gov.

Carl Gutierrez insisted Guam would implement labor laws familiar to the

United States and not commit the kinds of human-rights abuses that are

allegedly taking place in the Northern Marianas, which ended its

territorial status with the United States in 1986.

A

second major benefit of the law would be the release of Guam from the

Jones Act, which disallows ships from docking in two successive U.S.

ports without stopping at a foreign port in between.

Because of the law, many transporters traveling between Asia and the U.S. West Coast skip Guam in favor of larger markets. This has hampered the territory's import-export industry.

Because of the law, many transporters traveling between Asia and the U.S. West Coast skip Guam in favor of larger markets. This has hampered the territory's import-export industry.

Also,

the proposal would allow Guam the freedom to trade and have

relationships with foreign governments. Guam is subjected to U.S.

quotas, which prevent the island from developing a significant export

market.

Paul

Calvo, a former governor and president of a conglomerate, has testified

before U.S. Congressional committees, saying Guam suffers from U.S.

trade discrimination and an "imbalanced mercantile service economy

without significant industry or light assembly sectors."

Under the act, Guam's tax laws would remain in force for a year, then Guam would create new tax laws.

"That's

good and bad," said Allen Pickens, managing partner at Deloitte &Touche. "Good because we can draft our own and bad because the laws

could change on the whim of a political group."

Other

provisions in the act would grant Guam full control over its local

court system, similar to the way state and federal courts operate. And

Guam would have authority over its natural resources, including its

exclusive economic zone. Also all surplus federal land would revert to

Guam.

Finally,

the act would give the United States full charge of foreign affairs and

the defense of Guam, but would prohibit changes in military activity on

Guam without prior consultation. And it would give Guam authority to

request compensation for military and federal government use of land and

infrastructure.

Most businesspeople felt the policy change would do little to aid Guam's economy.

"It's

more emotion-driven than economics," said John Lee, a senior vice

president at First Hawaiian Bank, echoing the sentiments of several

businesspeople.

Said

Wali Osman, an economist specializing in the Asia-Pacific region at

Bank of Hawaii: "Whether it happens or doesn't happen, there will be no

real impact on the economy."

He added for investors, it would be business as usual if Guam became a commonwealth.

"The

U.S. flag -- that's Guam's greatest asset," he said. "People will still

want to do business there because it is American soil."

Under the proposal, the U.S. flag would continue to fly over Guam.

*******************

Press Release

GA/SPD/110

October 1997

Petitioners from Guam this morning objected to the current form of the omnibus draft resolution approved by the Special Committee on decolonization, stating that its language with respect to Guam had been weakened at the request of the United States, the administering Power. Addressing the Fourth Committee (Special Political and Decolonization), they urged the Main Committee of the General Assembly to reinstate the language used in prior years in the text it submitted to the Assembly for adoption, as the current version undermined the process of Guam's decolonization.

A representative of the Organization of People for Indigenous Rights said the "shameless changes" to the Guam portion of the text violated the purpose and mandate of the Fourth Committee. A senator from the Guam Legislature urged the United Nations to send a visiting mission to the Territory to personally hear the voices of the colonized Chamorro people, in order to better ascertain their situation.

Those two speakers were among eight petitioners who addressed the Committee this morning on the situation in Guam. The representative of the United States, in response, said that both his Government and that of Guam supported self-determination for the people of Guam, but differed on who would exercise that right. It should be exercised by all the people of Guam, he said. The United States could not support a self-determination process which excluded Guamanians who were not Chamorros. The representatives of Cuba, Papua New Guinea and Syria also spoke on the matter.

Also this morning, statements in the general debate on decolonization issues were made by the representatives of Brazil, Tunisia, Pakistan, Spain and the United Kingdom. The representative of the United Kingdom also spoke in exercise of the right of reply.

The Committee will meet again at 3 p.m. on Monday, 13 October, to conclude its general debate on decolonization matters and begin its consideration of the effects of atomic radiation.

Committee Work Programme

The Fourth Committee (Special Political and Decolonization) met this morning to continue its general debate on decolonization issues and hear petitioners on the question of Guam.

Statement of Committee Chairman

MACHIVENYIKA TOBIAS MAPURANGA (Zimbabwe), Committee Chairman, said that Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs Kieran Prendergast told him this morning that the Secretary-General had said it would be helpful for the sponsors of the draft resolution concerning the transfer of the decolonization unit (document A/C.4/52/L.4) to meet with him.

Hearing of Petitioners

ROBERT A. UNDERWOOD, delegate from Guam to the United States House of Representatives, said that the people of Guam had chosen to pursue a change in their political status, in the form of a commonwealth association with the United States. That choice was made in a series of locally authorized referendums between 1982 and 1987. However, such commonwealth status was intended to be an interim step; it did meet internationally recognized standards for decolonization and it was not independence. The Committee was urged to reaffirm the right to self-determination of Guam's indigenous people, the Chamorros. That principle was not negotiable. It would be inappropriate to consider removing Guam from the United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.

Although the United States Government had identified excess lands for return to Guam, it had yet to provide a process for their expeditious return, he said. In fact, the current process allowed federal agencies to bid for those lands ahead of Guam. The United States Mission had been asked to support a revised General Assembly resolution which would address Guam's quest for greater self-government.

MARK CAMPOS CHARFAUROS, Senator in Guam's Legislature, spoke on behalf of Antonio Unpingco, Speaker of the Guam Legislature. He said that since 1946, the United Nations had been confused by all the terms the United States used to describe Guam's people -- Chamorro, Guamanian, inhabitants of Guam and people of Guam. That was apparent in the current draft resolution on the matter and in the previously amended draft resolutions adopted by the Assembly during its session last year. That misconception was understandable, for the United States had given the impression that it considered two peoples when addressing the situation in Guam. The United States was not an angel, and would resort to deception and manipulation to further its agenda.

Reference to the people of Guam must consider the context of a colonized people, he said. One term used by the United States concerned a people, another concerned citizenship. The United Nations had assumed the Chamorro people's right to self-determination by including all American citizens in its resolution on the matter, and the present draft resolution continued that grave injustice. What had happened to the Chamorro people's good relationship with the Fourth Committee and the Special Committee on decolonization?

Sensing that the tide had turned, the Guam Legislature had passed a law to create the Commission on Decolonization for the Implementation and Exercise of Chamorro Self-Determination. Another Guam bill would protect the right of the Chamorro people to determine their political status and that of their homeland. Upcoming hearings in the United States House of Representatives would likely amount to nothing.

The Guam portion of the original text of the omnibus draft resolution on decolonization should be substituted for the current language, he said. The United Nations should send a visiting mission to Guam to personally hear the voices of the colonized Chamorro people, in order to better evaluate their situation.

LELAND BETTIS, Executive Director of the Guam Commission on Self Determination, speaking on behalf of the Governor of Guam, said that December would mark the fifty-first year since Guam had been inscribed on the list of Non-Self-Governing Territories. Since that time, nothing had fundamentally altered the colonial nature of its relationship with the United States. The administering Power extended its edicts without input from the representatives of Guam.

The people of Guam refused to be subject to the pageantry of a colonial beauty contest, he said. Chattel was chattel was chattel. Under the internal legal mechanism of the United States, Guam was mere property. There was no indication that that would change. The Fourth Committee was therefore called upon to carefully examine the situation.

He said that Guam's identification as a Territory was under threat. There was a concerted effort under way to strip the Special Committee on decolonization of its political mandate and its ability to interact with the Territories. Further, the administering Power now supported continuing Guam's colonial status. The administering Power's Mission to the United Nations had stated that the work of the Special Committee was finished. They had said that colonialism was finished.

Guam was a small island with a small population, and it was a colonial possession of the world's largest nation, he said. Its lands remained occupied, and the rules of government were subject to constant change without local input. The administering Power continued to present the Special Committee with inaccurate depictions of the situation in Guam. The portions of the Special Committee's omnibus resolution regarding Guam were therefore unacceptable.

Offers to support visiting missions to Guam had seemingly been withdrawn and promised measures of cooperation had not occurred, he said. The emasculation of the decolonization process by the administering Power should not be allowed. Guam would advance the decolonization process unilaterally if necessary. International standards should continue to be fully reflected in the Fourth Committee's consideration of the question.

HOPE ALVAREZ CRISTOBAL, Chairperson of the International Networking Committee of the Organization of People for Indigenous Rights, said that Guam's journey towards self-determination was at a critical juncture. It was important for the Fourth Committee to recognize that the question of Guam was one of decolonization. Guam should not be removed from the list of Non-Self- Governing Territories.

The administering Power had been negligent in its handling of Guam, she said. The proposed implementation of commonwealth status for Guam did not mean it would achieve self-determination. The administering Power had continuously tried to deny the Chamorro people their right to self- determination. Those efforts included an attempt to confuse the United Nations about the identity of the people of Guam. Several different names -- including "people of Guam", "Guamanians" and "Chamorros" -- had been used, making it seem that the people of Guam were a mixed bag.

The welfare of non-self-governing peoples such as the Chamorro people of Guam would continue to be compromised as long as the administering Power was allowed to negate their efforts at the highest levels of the United Nations, she said. It was a difficult pill to swallow, that the United Nations was willing to minimize commentary on the administering Power's sacred responsibility to promote self-government through decolonization. In the case of Guam, that process had stretched out for over half a century.

The Fourth Committee was asked to oppose the current language of the section on Guam in the Special Committee's omnibus resolution, she said. The shameless changes to that portion of the text, initiated by the United States, would violate the purpose and mandate of the Fourth Committee.

RONALD TEEHAN, of the Guam Landowners Association, said there had been a significant increase in pressure this year to pretend that colonial situations no longer existed, but nothing could be further from the truth. At the United Nations, the United States had attempted to undercut, if not eliminate, the decolonization process. The fact that Guam had conducted local elections did not make it self-governing. Was Guam self-governing when a United States agency could take land that belonged to its people? Guam's colonial status dramatically impeded its political and economic development. The Committee should regard with great suspicion any suggestion that colonial politics was the primary manifestation of self-government.

He said that Guam was not in position to control its resources or to make decisions about its future; the administering Power reserved those decisions to itself. The 1996 General Assembly resolution concerning the situation in Guam and the current draft resolution before the Committee actually undermined the process of Guam's decolonization. The United Nations decolonization process was becoming nothing more than an accelerated effort to declare the International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism by the Year 2000 a success.

The administering Power had raised concerns about the Chamorro people being the exclusive party to decide Guam's colonial status, he said. That was a cruel joke. The administering Power's immigration policy was clearly a colonization policy; only those who were colonized should decide Guam's decolonized status. Guam was inclined to reject any arguments that its requests should be to the political realities of the United Nations. He urged the reinstatement of the language adopted by the Special Committee in its 1996 resolution on the situation in Guam. The resolution should truly reflect the situation in Guam, rather than serve the purpose of a political expediency.

PEDRO NUNEZ-MOSQUERA (Cuba) said informal consultations between the Special Committee and the administering Power had produced the language of the draft resolution on the situation in Guam. Had there been any improvement in the situation as a result of those consultations?

Mr. TEEHAN said the consultations had not discernibly improved the situation. Rather, they had resulted in a further weakening of the section concerning Guam.

UTULA U. SAMANA (Papua New Guinea), Chairman of the Special Committee on decolonization, asked Mr. Teehan whether the Guam Commonwealth Act passed by the Guam Legislature had produced further movement on the situation on the island.

Mr. TEEHAN said that since the Act was passed 10 years ago, Guam had consistently brought the matter to the attention of the United States Government. A bill was now before the United States Congress, but hearings on it had been postponed several times. Implementation of the Act had not been supported financially by the United States Government, but had been funded locally, in Guam. Many portions of the Act had been attacked by agencies of the United States Government. Nothing concrete had occurred, except for 10 years of protracted discussion.

JOSE ULLOA GARRIDO, of the Nasion Chamoru, said the portion of the Special Committee's omnibus draft resolution concerning Guam was appalling. The Chamorro right to self-determination had fallen on deaf ears in the Special Committee. Lands taken by the United States must be returned. It was hard to accept that members of the Special Committee which were once colonies would accede to the changes to the draft resolution supported by the United States. Those changes cut through the soul of the Chamorro people.

The purpose and mission of the Fourth Committee to eradicate decolonization had been compromised, he said. The Special Committee had assigned to the United States the right to decolonize -- a right which belonged to the Chamorro people. Guam's colonizer had always been a master of intrigue and deception but it had not been expected that some members of the Special Committee would be co-opted. The United States had created a welfare state in Guam. It was tragic that some countries had joined the United States in condemning human rights abuses in China without condemning the treatment by the United States of indigenous peoples in its colonies.

The United States must unconditionally return all lands stolen from the Chamorros of Guam, he said. It had taken less than a month to take the lands; 50 years was too long for them to take in returning it. Further, all titles over and control of natural resources must be relinquished; all nuclear warheads and missiles must be removed, and all 36 hazardous and toxic waste sites must be cleaned. Visiting missions should be sent to Guam.

FAYSSAL MEKDAD (Syria) asked Mr. Garrido about the change in the language of the resolution. What language did he have in mind?

Mr. GARRIDO said he had been referring to items 1, 3, 4 and 5 of the 1997 version of the omnibus resolution.

PATRICIA ULLOA GARRIDO, representing the Ancestral Landowners Coalition of Guam, said the United States' continued withholding of land documents from the government of Guam, was a violation of treaty. In addition, repeated petitions on civil and human rights by Chamorro leaders had been ignored. It was ironic and evil that the United States expected substantial payment for the return of lands it had confiscated for military uses. That position was designed to create a sense of hopelessness and resignation among the Chamorro people. The Chamorro people would not pay for the return of their lands; they did not have the required funds.

PATRICK SAN NICOLAS, a Chamorro tribal chairman, said the draft resolution approved by the Special Committee on 20 June included a new and appalling change. The Chamorro tribe of the Marianas opposed any form of self-determination which surrendered the sovereignty rights of the Chamorro people.

The United States had divided the Chamorro people into two separate forms of government, he said. There was Guam, an unincorporated Territory of the United States, and there were the northern islands of the Marianas. The Chamorros were one nation and would not surrender their sovereign rights. The United Nations should recognize the sovereignty of the Chamorros people and the United States should be urged to recognize the Chamorros of the Marianas. The Chamorro people could then begin to experience true sovereignty.

DAVID SCOTT (United States), said his Government and that of Guam supported the self-determination for the people of Guam but differed on who would exercise that right. That right should be exercised by all the people of Guam. Petitioners who had spoken today had asked only that a portion of the population of Guam be allowed to exercise that right. The United States could not endorse a process which excluded Guamanians who were not Chamorros. The ultimate outcome of the self-determination process would depend on its ability to include all citizens in its scope.

General Debate on Decolonization

HENRIQUE R. VALLE (Brazil) said his delegation fully endorsed statements made yesterday by Paraguay on behalf of the Rio Group, as well as by Uruguay, on behalf of the Common Market of the Southern Cone (MERCOSUR), Bolivia and Chile. He reiterated Brazil's support for the Declaration on the Malvinas Islands adopted last year by MERCOSUR, Bolivia and Chile.

With respect to East Timor, Brazil had always stressed the importance of a fair and internationally acceptable solution, he said. Hope was placed in direct talks between the parties involved. Brazil strongly supported the tripartite process being held under the auspices of the Secretary-General, as well as the All-Inclusive East Timorese Dialogue.

He drew attention to a resolution adopted in July by the Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries, meeting in Brazil, which established the categories of "associated observers", "permanent observers" and "invited observers". That decision allowed for the presence in East Timor of representatives of all interested political trends, without the predominance of any of the parties or political movements there.

EL WALID DOUDECH (Tunisia) said that it was necessary to strengthen the trend of international cooperation in order to eliminate colonialism by the end of the century. Although the time was short, there was reason to be optimistic. The Special Committee's omnibus resolution last year had established principles; practical measures for the next stage of the process must now be defined. A programme for cooperation between the Special Committee and the administering Powers must be devised as a matter of priority. The aspirations of the Non-Self-Governing Territories must be recognized.

While there were a variety of options in the decolonization process, free choice by the concerned people was the key, he said. One of the questions facing the Special Committee concerned the appropriate means for ascertaining the nature of those aspirations. Such means varied, and it was appropriate to consider each case individually. Visiting missions were an effective means, and consultations should begin to organize such missions to relevant Territories.

MIAN ABDUL WAHEED (Pakistan) said that the increase in the United Nations membership from 51 to 185 States was a clear testimony to its success and achievements. It was a matter of immense satisfaction that over 60 former colonial Territories had joined the community of independent nations. The peoples of the remaining 17 Non-Self-Governing Territories looked to the United Nations for their freedom. Efforts must be consolidated to end colonialism. The positive response of the administering Powers was welcomed. Greater pragmatism and innovation was needed in considering the issue.

Pakistan had achieved independence through the exercise of its right to self-determination and considered it a moral duty to support peoples which were under alien subjugation, he said. Unfortunately, the right to self- determination had been smothered in many parts of the world. That had occurred in the case of the Kashmiri people, under occupation by India. Inhuman repression and persecution had occurred, and 60,000 Kashmiris had been killed. The Indian claim that Jammu and Kashmir were an integral part of India was a farce. It was a case of neo-colonialism. Denial of the rights of the Kashmiri people was a violation of the Charter of the United Nations and of international law.

JAVIER PEREZ-GRIFFO (Spain) said that despite the United Nations achievements in decolonization, unresolved issues remained. There was no single recipe by which to terminate colonialism. The Organization should ensure that the peoples of the 17 remaining Non-Self-Governing Territories could observe their right to self-determination.

The situation on Gibraltar had peculiar features, he said. The Rock of Gibraltar was acquired by force during the eighteenth century. However, the peninsula did not cease to be Spanish. Also, the isthmus above it was acquired illegally and gradually by the United Kingdom. The survival of this last colony was difficult to reconcile with the modern world. Gibraltar was converted to a military base by the United Kingdom, which expelled the Spanish people there.

In the United Nations, there was clear doctrine on Gibraltar, which urged the United Kingdom to end colonial domination there, he said. Several General Assembly resolutions had reiterated the principle of territorial integrity with respect to Gibraltar. Negotiations between Spain and the United Kingdom on the situation had begun in 1985, and Spain remained firmly committed to dialogue in the hope that negotiations would end the Gibraltar dispute.

The Treaty of Utrecht established Spanish sovereignty over Gibraltar should it cease to be under British rule, he said. Spanish authorities had stated their respect for the legitimate interests of the population of Gibraltar, as well as for their identity and characteristics. Spain was ready to make a very generous offer, that once reincorporation of Gibraltar with Spain had taken place, efforts would be made to improve the economic situation of its people.

KATE SMITH (United Kingdom) said the United Kingdom considered the rights of the peoples of the Territories to be of paramount importance in determining their futures. Within the restraints of treaty obligations, the constitutional framework in each of the United Kingdom's Territories sought to reflect the wishes and interests of their peoples. Each of the Territories held regular and free elections. Indeed, the inhabitants of the Falkland Islands had exercised their democratic rights in an election yesterday.

She expressed dismay at statements made before the Committee this week implying that the choice of independence was the only possible outcome of the free exercise of self-determination. That was not the case. The vast majority of people in the British Territories were content with their basic relationship and with the degree of self-government they had achieved.

The United Kingdom recognized the important advances made on the text of the Special Committee's draft resolution with respect to "economic activities", she said. However, it was important to note that foreign economic activities did not always do the Territories more harm than good. Often, the contrary was the case. Foreign investment was a valuable source of income for a number of the United Kingdom's Territories, helping them to achieve a greater degree of self-sufficiency.

The United Kingdom would continue to support the people of Montserrat in their plight, she said. Those wishing to leave Montserrat would be assisted. Statements made this week by representatives from the Caribbean region calling for support for the people of Montserrat had been appreciated.

The Committee then approved a request for a hearing by a petitioner on the question of New Caledonia for the week of 13 October.

Right of Reply

KATE SMITH (United Kingdom), speaking in exercise of the right of reply, said the position of the United Kingdom with respect to the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) and Gibraltar had been laid out in the right of reply statements by the United Kingdom before the General Assembly on 24 and 26 September.

* *** *

*******************

PETITIONERS FROM GUAM OBJECT TO CHANGES IN DECOLONIZATION DRAFT, URGE FOURTH COMMITTEE TO RESTORE ORIGINAL LANGUAGE

United Nations General AssemblyPress Release

GA/SPD/110

October 1997

Petitioners from Guam this morning objected to the current form of the omnibus draft resolution approved by the Special Committee on decolonization, stating that its language with respect to Guam had been weakened at the request of the United States, the administering Power. Addressing the Fourth Committee (Special Political and Decolonization), they urged the Main Committee of the General Assembly to reinstate the language used in prior years in the text it submitted to the Assembly for adoption, as the current version undermined the process of Guam's decolonization.

A representative of the Organization of People for Indigenous Rights said the "shameless changes" to the Guam portion of the text violated the purpose and mandate of the Fourth Committee. A senator from the Guam Legislature urged the United Nations to send a visiting mission to the Territory to personally hear the voices of the colonized Chamorro people, in order to better ascertain their situation.

Those two speakers were among eight petitioners who addressed the Committee this morning on the situation in Guam. The representative of the United States, in response, said that both his Government and that of Guam supported self-determination for the people of Guam, but differed on who would exercise that right. It should be exercised by all the people of Guam, he said. The United States could not support a self-determination process which excluded Guamanians who were not Chamorros. The representatives of Cuba, Papua New Guinea and Syria also spoke on the matter.

Also this morning, statements in the general debate on decolonization issues were made by the representatives of Brazil, Tunisia, Pakistan, Spain and the United Kingdom. The representative of the United Kingdom also spoke in exercise of the right of reply.

The Committee will meet again at 3 p.m. on Monday, 13 October, to conclude its general debate on decolonization matters and begin its consideration of the effects of atomic radiation.

Committee Work Programme

The Fourth Committee (Special Political and Decolonization) met this morning to continue its general debate on decolonization issues and hear petitioners on the question of Guam.

Statement of Committee Chairman

MACHIVENYIKA TOBIAS MAPURANGA (Zimbabwe), Committee Chairman, said that Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs Kieran Prendergast told him this morning that the Secretary-General had said it would be helpful for the sponsors of the draft resolution concerning the transfer of the decolonization unit (document A/C.4/52/L.4) to meet with him.

Hearing of Petitioners

ROBERT A. UNDERWOOD, delegate from Guam to the United States House of Representatives, said that the people of Guam had chosen to pursue a change in their political status, in the form of a commonwealth association with the United States. That choice was made in a series of locally authorized referendums between 1982 and 1987. However, such commonwealth status was intended to be an interim step; it did meet internationally recognized standards for decolonization and it was not independence. The Committee was urged to reaffirm the right to self-determination of Guam's indigenous people, the Chamorros. That principle was not negotiable. It would be inappropriate to consider removing Guam from the United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.

Although the United States Government had identified excess lands for return to Guam, it had yet to provide a process for their expeditious return, he said. In fact, the current process allowed federal agencies to bid for those lands ahead of Guam. The United States Mission had been asked to support a revised General Assembly resolution which would address Guam's quest for greater self-government.

MARK CAMPOS CHARFAUROS, Senator in Guam's Legislature, spoke on behalf of Antonio Unpingco, Speaker of the Guam Legislature. He said that since 1946, the United Nations had been confused by all the terms the United States used to describe Guam's people -- Chamorro, Guamanian, inhabitants of Guam and people of Guam. That was apparent in the current draft resolution on the matter and in the previously amended draft resolutions adopted by the Assembly during its session last year. That misconception was understandable, for the United States had given the impression that it considered two peoples when addressing the situation in Guam. The United States was not an angel, and would resort to deception and manipulation to further its agenda.

Reference to the people of Guam must consider the context of a colonized people, he said. One term used by the United States concerned a people, another concerned citizenship. The United Nations had assumed the Chamorro people's right to self-determination by including all American citizens in its resolution on the matter, and the present draft resolution continued that grave injustice. What had happened to the Chamorro people's good relationship with the Fourth Committee and the Special Committee on decolonization?

Sensing that the tide had turned, the Guam Legislature had passed a law to create the Commission on Decolonization for the Implementation and Exercise of Chamorro Self-Determination. Another Guam bill would protect the right of the Chamorro people to determine their political status and that of their homeland. Upcoming hearings in the United States House of Representatives would likely amount to nothing.

The Guam portion of the original text of the omnibus draft resolution on decolonization should be substituted for the current language, he said. The United Nations should send a visiting mission to Guam to personally hear the voices of the colonized Chamorro people, in order to better evaluate their situation.

LELAND BETTIS, Executive Director of the Guam Commission on Self Determination, speaking on behalf of the Governor of Guam, said that December would mark the fifty-first year since Guam had been inscribed on the list of Non-Self-Governing Territories. Since that time, nothing had fundamentally altered the colonial nature of its relationship with the United States. The administering Power extended its edicts without input from the representatives of Guam.

The people of Guam refused to be subject to the pageantry of a colonial beauty contest, he said. Chattel was chattel was chattel. Under the internal legal mechanism of the United States, Guam was mere property. There was no indication that that would change. The Fourth Committee was therefore called upon to carefully examine the situation.

He said that Guam's identification as a Territory was under threat. There was a concerted effort under way to strip the Special Committee on decolonization of its political mandate and its ability to interact with the Territories. Further, the administering Power now supported continuing Guam's colonial status. The administering Power's Mission to the United Nations had stated that the work of the Special Committee was finished. They had said that colonialism was finished.

Guam was a small island with a small population, and it was a colonial possession of the world's largest nation, he said. Its lands remained occupied, and the rules of government were subject to constant change without local input. The administering Power continued to present the Special Committee with inaccurate depictions of the situation in Guam. The portions of the Special Committee's omnibus resolution regarding Guam were therefore unacceptable.

Offers to support visiting missions to Guam had seemingly been withdrawn and promised measures of cooperation had not occurred, he said. The emasculation of the decolonization process by the administering Power should not be allowed. Guam would advance the decolonization process unilaterally if necessary. International standards should continue to be fully reflected in the Fourth Committee's consideration of the question.

HOPE ALVAREZ CRISTOBAL, Chairperson of the International Networking Committee of the Organization of People for Indigenous Rights, said that Guam's journey towards self-determination was at a critical juncture. It was important for the Fourth Committee to recognize that the question of Guam was one of decolonization. Guam should not be removed from the list of Non-Self- Governing Territories.

The administering Power had been negligent in its handling of Guam, she said. The proposed implementation of commonwealth status for Guam did not mean it would achieve self-determination. The administering Power had continuously tried to deny the Chamorro people their right to self- determination. Those efforts included an attempt to confuse the United Nations about the identity of the people of Guam. Several different names -- including "people of Guam", "Guamanians" and "Chamorros" -- had been used, making it seem that the people of Guam were a mixed bag.

The welfare of non-self-governing peoples such as the Chamorro people of Guam would continue to be compromised as long as the administering Power was allowed to negate their efforts at the highest levels of the United Nations, she said. It was a difficult pill to swallow, that the United Nations was willing to minimize commentary on the administering Power's sacred responsibility to promote self-government through decolonization. In the case of Guam, that process had stretched out for over half a century.

The Fourth Committee was asked to oppose the current language of the section on Guam in the Special Committee's omnibus resolution, she said. The shameless changes to that portion of the text, initiated by the United States, would violate the purpose and mandate of the Fourth Committee.

RONALD TEEHAN, of the Guam Landowners Association, said there had been a significant increase in pressure this year to pretend that colonial situations no longer existed, but nothing could be further from the truth. At the United Nations, the United States had attempted to undercut, if not eliminate, the decolonization process. The fact that Guam had conducted local elections did not make it self-governing. Was Guam self-governing when a United States agency could take land that belonged to its people? Guam's colonial status dramatically impeded its political and economic development. The Committee should regard with great suspicion any suggestion that colonial politics was the primary manifestation of self-government.

He said that Guam was not in position to control its resources or to make decisions about its future; the administering Power reserved those decisions to itself. The 1996 General Assembly resolution concerning the situation in Guam and the current draft resolution before the Committee actually undermined the process of Guam's decolonization. The United Nations decolonization process was becoming nothing more than an accelerated effort to declare the International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism by the Year 2000 a success.

The administering Power had raised concerns about the Chamorro people being the exclusive party to decide Guam's colonial status, he said. That was a cruel joke. The administering Power's immigration policy was clearly a colonization policy; only those who were colonized should decide Guam's decolonized status. Guam was inclined to reject any arguments that its requests should be to the political realities of the United Nations. He urged the reinstatement of the language adopted by the Special Committee in its 1996 resolution on the situation in Guam. The resolution should truly reflect the situation in Guam, rather than serve the purpose of a political expediency.

PEDRO NUNEZ-MOSQUERA (Cuba) said informal consultations between the Special Committee and the administering Power had produced the language of the draft resolution on the situation in Guam. Had there been any improvement in the situation as a result of those consultations?

Mr. TEEHAN said the consultations had not discernibly improved the situation. Rather, they had resulted in a further weakening of the section concerning Guam.

UTULA U. SAMANA (Papua New Guinea), Chairman of the Special Committee on decolonization, asked Mr. Teehan whether the Guam Commonwealth Act passed by the Guam Legislature had produced further movement on the situation on the island.

Mr. TEEHAN said that since the Act was passed 10 years ago, Guam had consistently brought the matter to the attention of the United States Government. A bill was now before the United States Congress, but hearings on it had been postponed several times. Implementation of the Act had not been supported financially by the United States Government, but had been funded locally, in Guam. Many portions of the Act had been attacked by agencies of the United States Government. Nothing concrete had occurred, except for 10 years of protracted discussion.

JOSE ULLOA GARRIDO, of the Nasion Chamoru, said the portion of the Special Committee's omnibus draft resolution concerning Guam was appalling. The Chamorro right to self-determination had fallen on deaf ears in the Special Committee. Lands taken by the United States must be returned. It was hard to accept that members of the Special Committee which were once colonies would accede to the changes to the draft resolution supported by the United States. Those changes cut through the soul of the Chamorro people.

The purpose and mission of the Fourth Committee to eradicate decolonization had been compromised, he said. The Special Committee had assigned to the United States the right to decolonize -- a right which belonged to the Chamorro people. Guam's colonizer had always been a master of intrigue and deception but it had not been expected that some members of the Special Committee would be co-opted. The United States had created a welfare state in Guam. It was tragic that some countries had joined the United States in condemning human rights abuses in China without condemning the treatment by the United States of indigenous peoples in its colonies.

The United States must unconditionally return all lands stolen from the Chamorros of Guam, he said. It had taken less than a month to take the lands; 50 years was too long for them to take in returning it. Further, all titles over and control of natural resources must be relinquished; all nuclear warheads and missiles must be removed, and all 36 hazardous and toxic waste sites must be cleaned. Visiting missions should be sent to Guam.

FAYSSAL MEKDAD (Syria) asked Mr. Garrido about the change in the language of the resolution. What language did he have in mind?

Mr. GARRIDO said he had been referring to items 1, 3, 4 and 5 of the 1997 version of the omnibus resolution.

PATRICIA ULLOA GARRIDO, representing the Ancestral Landowners Coalition of Guam, said the United States' continued withholding of land documents from the government of Guam, was a violation of treaty. In addition, repeated petitions on civil and human rights by Chamorro leaders had been ignored. It was ironic and evil that the United States expected substantial payment for the return of lands it had confiscated for military uses. That position was designed to create a sense of hopelessness and resignation among the Chamorro people. The Chamorro people would not pay for the return of their lands; they did not have the required funds.

PATRICK SAN NICOLAS, a Chamorro tribal chairman, said the draft resolution approved by the Special Committee on 20 June included a new and appalling change. The Chamorro tribe of the Marianas opposed any form of self-determination which surrendered the sovereignty rights of the Chamorro people.

The United States had divided the Chamorro people into two separate forms of government, he said. There was Guam, an unincorporated Territory of the United States, and there were the northern islands of the Marianas. The Chamorros were one nation and would not surrender their sovereign rights. The United Nations should recognize the sovereignty of the Chamorros people and the United States should be urged to recognize the Chamorros of the Marianas. The Chamorro people could then begin to experience true sovereignty.

DAVID SCOTT (United States), said his Government and that of Guam supported the self-determination for the people of Guam but differed on who would exercise that right. That right should be exercised by all the people of Guam. Petitioners who had spoken today had asked only that a portion of the population of Guam be allowed to exercise that right. The United States could not endorse a process which excluded Guamanians who were not Chamorros. The ultimate outcome of the self-determination process would depend on its ability to include all citizens in its scope.

General Debate on Decolonization

HENRIQUE R. VALLE (Brazil) said his delegation fully endorsed statements made yesterday by Paraguay on behalf of the Rio Group, as well as by Uruguay, on behalf of the Common Market of the Southern Cone (MERCOSUR), Bolivia and Chile. He reiterated Brazil's support for the Declaration on the Malvinas Islands adopted last year by MERCOSUR, Bolivia and Chile.

With respect to East Timor, Brazil had always stressed the importance of a fair and internationally acceptable solution, he said. Hope was placed in direct talks between the parties involved. Brazil strongly supported the tripartite process being held under the auspices of the Secretary-General, as well as the All-Inclusive East Timorese Dialogue.

He drew attention to a resolution adopted in July by the Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries, meeting in Brazil, which established the categories of "associated observers", "permanent observers" and "invited observers". That decision allowed for the presence in East Timor of representatives of all interested political trends, without the predominance of any of the parties or political movements there.

EL WALID DOUDECH (Tunisia) said that it was necessary to strengthen the trend of international cooperation in order to eliminate colonialism by the end of the century. Although the time was short, there was reason to be optimistic. The Special Committee's omnibus resolution last year had established principles; practical measures for the next stage of the process must now be defined. A programme for cooperation between the Special Committee and the administering Powers must be devised as a matter of priority. The aspirations of the Non-Self-Governing Territories must be recognized.

While there were a variety of options in the decolonization process, free choice by the concerned people was the key, he said. One of the questions facing the Special Committee concerned the appropriate means for ascertaining the nature of those aspirations. Such means varied, and it was appropriate to consider each case individually. Visiting missions were an effective means, and consultations should begin to organize such missions to relevant Territories.

MIAN ABDUL WAHEED (Pakistan) said that the increase in the United Nations membership from 51 to 185 States was a clear testimony to its success and achievements. It was a matter of immense satisfaction that over 60 former colonial Territories had joined the community of independent nations. The peoples of the remaining 17 Non-Self-Governing Territories looked to the United Nations for their freedom. Efforts must be consolidated to end colonialism. The positive response of the administering Powers was welcomed. Greater pragmatism and innovation was needed in considering the issue.

Pakistan had achieved independence through the exercise of its right to self-determination and considered it a moral duty to support peoples which were under alien subjugation, he said. Unfortunately, the right to self- determination had been smothered in many parts of the world. That had occurred in the case of the Kashmiri people, under occupation by India. Inhuman repression and persecution had occurred, and 60,000 Kashmiris had been killed. The Indian claim that Jammu and Kashmir were an integral part of India was a farce. It was a case of neo-colonialism. Denial of the rights of the Kashmiri people was a violation of the Charter of the United Nations and of international law.

JAVIER PEREZ-GRIFFO (Spain) said that despite the United Nations achievements in decolonization, unresolved issues remained. There was no single recipe by which to terminate colonialism. The Organization should ensure that the peoples of the 17 remaining Non-Self-Governing Territories could observe their right to self-determination.

The situation on Gibraltar had peculiar features, he said. The Rock of Gibraltar was acquired by force during the eighteenth century. However, the peninsula did not cease to be Spanish. Also, the isthmus above it was acquired illegally and gradually by the United Kingdom. The survival of this last colony was difficult to reconcile with the modern world. Gibraltar was converted to a military base by the United Kingdom, which expelled the Spanish people there.

In the United Nations, there was clear doctrine on Gibraltar, which urged the United Kingdom to end colonial domination there, he said. Several General Assembly resolutions had reiterated the principle of territorial integrity with respect to Gibraltar. Negotiations between Spain and the United Kingdom on the situation had begun in 1985, and Spain remained firmly committed to dialogue in the hope that negotiations would end the Gibraltar dispute.

The Treaty of Utrecht established Spanish sovereignty over Gibraltar should it cease to be under British rule, he said. Spanish authorities had stated their respect for the legitimate interests of the population of Gibraltar, as well as for their identity and characteristics. Spain was ready to make a very generous offer, that once reincorporation of Gibraltar with Spain had taken place, efforts would be made to improve the economic situation of its people.

KATE SMITH (United Kingdom) said the United Kingdom considered the rights of the peoples of the Territories to be of paramount importance in determining their futures. Within the restraints of treaty obligations, the constitutional framework in each of the United Kingdom's Territories sought to reflect the wishes and interests of their peoples. Each of the Territories held regular and free elections. Indeed, the inhabitants of the Falkland Islands had exercised their democratic rights in an election yesterday.

She expressed dismay at statements made before the Committee this week implying that the choice of independence was the only possible outcome of the free exercise of self-determination. That was not the case. The vast majority of people in the British Territories were content with their basic relationship and with the degree of self-government they had achieved.

The United Kingdom recognized the important advances made on the text of the Special Committee's draft resolution with respect to "economic activities", she said. However, it was important to note that foreign economic activities did not always do the Territories more harm than good. Often, the contrary was the case. Foreign investment was a valuable source of income for a number of the United Kingdom's Territories, helping them to achieve a greater degree of self-sufficiency.

The United Kingdom would continue to support the people of Montserrat in their plight, she said. Those wishing to leave Montserrat would be assisted. Statements made this week by representatives from the Caribbean region calling for support for the people of Montserrat had been appreciated.

The Committee then approved a request for a hearing by a petitioner on the question of New Caledonia for the week of 13 October.

Right of Reply

KATE SMITH (United Kingdom), speaking in exercise of the right of reply, said the position of the United Kingdom with respect to the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) and Gibraltar had been laid out in the right of reply statements by the United Kingdom before the General Assembly on 24 and 26 September.

* *** *

For information media. Not an official record.

Comments