The Chamorro Experience gi Fino' Chamorro

For thousands of years the Chamorro people have used the Chamorro language to tell their complicated story.

When Magellan arrived in ships filled with starving and

sickly sailors, Chamorros greeted him in the Chamorro language. When the

Spanish and other Europeans stopped in Guam to trade with Chamorros bits of

iron for rice, water and fruits, Chamorros greeted them in Chamorro. Even

during the Spanish Chamorro Wars, both those who fought against the Spanish

such as Hurao, Agualin or Chelef did so in Chamorro, giving grand speeches

trying to inspire courage. But even those who sided with the Spanish, like

Hineti and Ayihi and pledged their spears to defend the earthly representatives

of an invisible deity they had just met, they did so in the Chamorro language.

Even as Chamorros started to become Catholic and accept the

new faith in their lives, they used Chamorro, albeit infused with some Spanish,

in order to experience their religion. When the Americans arrived replacing one

colonizer with another, Chamorros learned a new language, but kept to their

own. They talked about the new opportunities the Americans were bringing, but

also complained about their racism and discrimination all in the Chamorro

language.

During the Japanese period the language was once again a

shield. At a time when not bowing properly to a Japanese soldier could get you

beaten, the Chamorro language provided a means of expressing oneself while

protecting yourself. Chamorros created songs that mocked the Japanese and would

sometimes sing them within earshot, leaving the Japanese to question in

ignorance whether the song was offensive or not.

Even in the time before colonizers, the Chamorro language

was still there. It was the soundtrack to the erecting of latte homes, of

voyages across oceans, battles between villages, and the venerating of

ancestors.

Since World War II the language has declined rapidly. It is

no longer actively being spoken to younger generations. Today, Chamorros use

English as the primary means of expressing themselves and talking about their

experiences. For most Chamorros born after World War II, the language exists,

and they hear it and may even use it in some ways, but it is fundamentally divorced

from their experiences. For describing their daily lives, their desires, their

emotions, their goals, English feels more comfortable.

The Chamorro language has long been used to tell our story,

but it also represents in and of itself, our story and our history. The

Austronesian roots, the core of the language still persists, but other

languages have changed it and influenced it as well. It is the sum of all our

complicated parts. To use contemporary Chamorro means to use a living

linguistic organism that connects you to people in Europe, Asia and the

Pacific. From a language, we can analyze the values of a people, their

psychology and epistemology.

The Chamorro language has for thousands of years been the

means through which Chamorros connected to each other and to the world. It

survived and adapted as the Chamorro people survived and adapted. It is truly

tragic to see that within a few generations it may disappear. When our manamko’

today pass on, they will take most of the language with them, since they did

not actively pass it on to the generations that followed them. To go from 100%

fluency to 4% fluency in three generations means that a language will be alive

and vibrant only as long as that generation of manamko’ is around. Once they pass

on, the Chamorro language will go the way of the songs of native birds, it will

be quieted and eventually close to silence.

It is important that we teach it to our children and support

their learning it and using it. It is imperative that we keep the ability to

tell our stories in the Chamorro language.

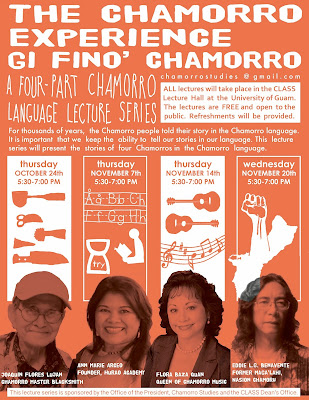

This week the University of Guam President’s Office and

Chamorro Studies program are premiering a new lecture series, a Chamorro

language lecture series. Its title, “The Chamorro Experience gi Fino’

Chamorro.”

Over the course of the next month, we will host four

Chamorro language lectures, each from a Chamorro who will talk about their

experiences and their perspectives. They come from very different walks of life

and very different perspectives, and the focus is not necessarily on the

Chamorro language, but rather the nexus between their experiences and the

Chamorro language. Having a lecture series like this won’t “save” the Chamorro

language, but if it can inspire some fluent Chamorro speakers in the audience

to use it more around those younger than them, or inspire some young would-be

speakers to really commit to learning and using the language, then the series

will be well worth it.

Our first speaker is Tun Jack lujan, the Chamorro Master

Blacksmith. On October 24th, at 5:30 pm at the CLASS Lecture Hall in

the University of Guam he will be giving a lecture on the Chamorro traditional

tools to which he has devoted his life to preserving and promoting. The

lectures are free and open to the public and some refreshments will be

provided. Following the lecture a Q and A session will take place.

The remaining speakers are: Ann Marie Arceo, founder of Hurao Academy (11/7), Flora Baza Queen, Queen of Chamorro Music (11/14) and Eddie LG Benavente, former Maga'lahi of Nasion Chamoru (11/20).

Comments