Island of Historians and Chi Bi

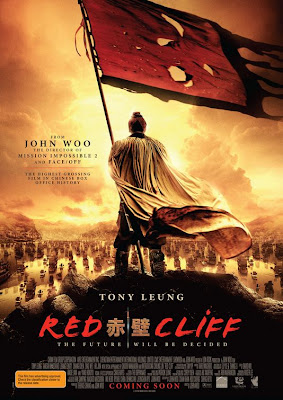

I finally got to watch both parts of the epic Chinese war movie Chi Bi the other night. For those of you who haven't heard of it, it is directed by John Woo, and was released a month before the start of the 2008 Olympics and was meant to be a show of China's movie-making force to the rest of the world. It is the most expensive Chinese film to date and now its highest grossing film as well.

I finally got to watch both parts of the epic Chinese war movie Chi Bi the other night. For those of you who haven't heard of it, it is directed by John Woo, and was released a month before the start of the 2008 Olympics and was meant to be a show of China's movie-making force to the rest of the world. It is the most expensive Chinese film to date and now its highest grossing film as well.The title of the film Chi Bi translates to "red wall" or "red cliffs" in English, and is based on the battle of Chi Bi which took place almost two thousand years ago, and is infamously chronicled in the story Romance of the Three Kingdoms and the video game series Dynasty Warriors.

To give a little bit of background on the event. This battle takes place prior to the Three Kingdoms era in Chinese history, and is actually a key reason why China had a three kingdoms era at all. During this period the Han dynasty is coming to a close, and different figures are vying for control over different territories within China. Three main figures emerge and eventually divide up the contested region into three kingdoms, with Liu Bei, Cao Cao and Sun Quan, each respectively the leaders of Shu, Wei and Wu. All of these figures and their armies were at Chi Bi.

The year prior to which the battle was fought, Cao Cao had taken complete control over the imperial throne and reduced the emperor to his puppet. He had already pacified the northern part of the kingdom which would later become Wei, and sought to extend his influence and conquer the west and the south, which meant taking down Liu Bei and Sun Quan. Cao Cao was by far the most powerful of the three, and boasted that he came to the battle of Chi Bi, which took place within Sun Quan's kingdom, with 800,000 men and a massive armada. Hoping to stop Cao Cao's perversion of the imperial throne and the spreading of his influence, Liu Bei and Sun Quan joined forces against him, and through a fair amount of bold action and trickery from Sun Quan's Viceroy Zhou Yu and Zhuge Liang, Liu Bei's main strategist, they defeated Cao Cao.

The film Chi Bi chronicles the march of Cao Cao south to Wu, the forging of an alliance between Wu and Shu, the deception and dirty tricks that both sides commit to try and gain an advantage and then ultimately the battle itself, where Cao Cao is defeated by the axiom that, in war the winner is whoever the weather is with. The Shu and Wu alliance was able to substantially weaken Cao Cao's forces by making two of his key generals appear as if they were traitors. These two generals were the only commanders that Cao Cao had who had real Naval experience. They had both fought regular battles in Southern China, usually against Wu and Sun Quan's father, Sun Jian. Cao Cao relied heavily upon them since all his other generals were from the north and had no experience on the water. Zhou Yu was able to fool Cao Cao into thinking they were traitors and he had them executed. When the battle eventually began, Cao Cao was severely limited by the fact that he had no generals who could read the weather and anticipate its changes and that he was fighting a naval battle with troops who did not have "sea legs." Cao Cao went so far to chain his ships together to create a stable platform for his troops. Both of these mistakes worked in favor of the Shu-Wu forces, who took advantage of the ships being chained together and a change in wind to strike with fire ships and destroy much of the armada.

The film Chi Bi chronicles the march of Cao Cao south to Wu, the forging of an alliance between Wu and Shu, the deception and dirty tricks that both sides commit to try and gain an advantage and then ultimately the battle itself, where Cao Cao is defeated by the axiom that, in war the winner is whoever the weather is with. The Shu and Wu alliance was able to substantially weaken Cao Cao's forces by making two of his key generals appear as if they were traitors. These two generals were the only commanders that Cao Cao had who had real Naval experience. They had both fought regular battles in Southern China, usually against Wu and Sun Quan's father, Sun Jian. Cao Cao relied heavily upon them since all his other generals were from the north and had no experience on the water. Zhou Yu was able to fool Cao Cao into thinking they were traitors and he had them executed. When the battle eventually began, Cao Cao was severely limited by the fact that he had no generals who could read the weather and anticipate its changes and that he was fighting a naval battle with troops who did not have "sea legs." Cao Cao went so far to chain his ships together to create a stable platform for his troops. Both of these mistakes worked in favor of the Shu-Wu forces, who took advantage of the ships being chained together and a change in wind to strike with fire ships and destroy much of the armada. The movie uses this battle as the backdrop, but like the video game Dynasty Warriors, the action is all character and personality based. There is plenty of fighting and violence, explosions and death, don't get me wrong. But the film is also more than four hours long, and much of it is spent on the developing of characters and the developing of their relationships. Much of the film is fictionalized, meaning that certain events in the film simply didn't happen according to the historical record, but were created to give the film more drama or make it more exciting. But nearly all of persons involved were real historical figures and probably have thesises written on them, or movies or books about them. And it is on these figures and developing them that the movie is actually focused. It gets frustrating at certain points, as characters are given motivations, thoughts or actions in the film, that if you're familiar with the history or even the novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, you know they certainly did not possess. A case in point is the close friendship and admiration that Zhou Yu and Zhuge Liang develop in the film. Although it is rocky at certain points, they forge an intimacy and a dialogue, a working off of each other that drives the action and provides the narrative rationale for the film. But this isn't just slightly different than what I know from the historical record, its almost completely different. Prior to the battle Zhou Yu attempted to assassinate both Zhuge Liang and Liu Bei several times.

The movie uses this battle as the backdrop, but like the video game Dynasty Warriors, the action is all character and personality based. There is plenty of fighting and violence, explosions and death, don't get me wrong. But the film is also more than four hours long, and much of it is spent on the developing of characters and the developing of their relationships. Much of the film is fictionalized, meaning that certain events in the film simply didn't happen according to the historical record, but were created to give the film more drama or make it more exciting. But nearly all of persons involved were real historical figures and probably have thesises written on them, or movies or books about them. And it is on these figures and developing them that the movie is actually focused. It gets frustrating at certain points, as characters are given motivations, thoughts or actions in the film, that if you're familiar with the history or even the novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, you know they certainly did not possess. A case in point is the close friendship and admiration that Zhou Yu and Zhuge Liang develop in the film. Although it is rocky at certain points, they forge an intimacy and a dialogue, a working off of each other that drives the action and provides the narrative rationale for the film. But this isn't just slightly different than what I know from the historical record, its almost completely different. Prior to the battle Zhou Yu attempted to assassinate both Zhuge Liang and Liu Bei several times.Regardless of these changes, I still loved this movie because it provided so much new life and energy to historical Chinese figures that I've come to know in different ways over the years. Even if the film wasn't historically accurate, we shouldn't look to these sorts of films for anything about the past. Although they are dealing in history, they are working with history, they aren't meant to recreate history, or provide an accurate snapshot of that time. If you look for these sorts of things, you'll always be disappointed. This is of course why for me these films should be appreciated or analyzed for what they say about or what they do to the present. The changes that directors, editors, writers, actors or artists make in films dealing with long gone historical subjects are always meant to reflect the changes in attitudes or tastes of people today.

So in Chi Bi, like in all war movies the battles themselves are simplified, made shorter and less sprawling in order to pack them into an exciting and bombastic period of film time. The protagonists and antagonists are made clearer and sharpened to the point where one represents the best of humanity, freedom, liberty and creativity, while the other is oppression, and unchecked, evil power. Women characters are given larger roles and allowed to join in the action, far more than history and history books would ever allow. Furthermore, this film itself is made in order to represent China and Chinese culture and history to the world. History thus must be shaped to create something which is worthy of representing China, something which inspires, something which asserts China's historical and contemporary greatness and grandness. Most importantly though, is that the film has to be made to something which people of today can "enjoy" something that appeals to them and their sensibilities.

So in Chi Bi, like in all war movies the battles themselves are simplified, made shorter and less sprawling in order to pack them into an exciting and bombastic period of film time. The protagonists and antagonists are made clearer and sharpened to the point where one represents the best of humanity, freedom, liberty and creativity, while the other is oppression, and unchecked, evil power. Women characters are given larger roles and allowed to join in the action, far more than history and history books would ever allow. Furthermore, this film itself is made in order to represent China and Chinese culture and history to the world. History thus must be shaped to create something which is worthy of representing China, something which inspires, something which asserts China's historical and contemporary greatness and grandness. Most importantly though, is that the film has to be made to something which people of today can "enjoy" something that appeals to them and their sensibilities.But whenever I see these sorts of large epics, which do far more to make the history of the world in people's minds than anything else, and anything which we could argue is more historically accurate, I am always reminded of Guam and ways in which we consider and envision our own relationship to Chamorro and Guam history. When I first started on my own path to becoming an academic, and seeing the history of Chamorro intellectuals and also the tone of Chamorro critical thinking, I was often struck at how history focused everything was. So much of what people who were critical or who were progressive from a Chamorro perspective were primarily committed to telling a different history or the real history, there were plenty of Chamorro historians, everyone seemed interested in getting better histories written.

Sometimes I've referred to Guam as an island of historians, or Chamorros as a historian people. When I say this, I don't mean that Chamorros are or Guam is very knowledgeable about their histories, that they take them very seriously or have some special insight to them that others don't. What I mean is that Chamorros, sometimes appear to be obsessed with a certain authenticity or accuracy to their history, which goes far beyond an everyday quality, but sometimes appears to be almost maniacal or pointless. They approach or envision their history and the ways it can be told or articulated as something which can only be accomplished in a single way, "the authentic" or the "right" way. But while we can all see the commonsensical lure to this sort of desire (the truth is its own reason), we should also know that its nonetheless a ridiculous one, and it is such in a number of equally commonsensical ways. Histories are always fictions, always vain, but perhaps noble attempts to take a multitude of constantly contradictions points and weave them together into a flowing narrative, a static snap shot, an episode edited for television, something which communicates a positive or a negative lesson, something which gives a clear view, a muddled view, an always impossible view, whose only certainty can be that, regardless of whatever authenticity comes attached to that history, that it is never actually certain. The ways in which the film Chi Bi, and the video game series Dynasty Warriors, academic texts on that period of Chinese history, all of them together tell that history, and although we might admit to one of the domains of knowledge possessing more historical accuracy than the others, that has little effect on

The "truth" does not possess any magical power. The accuracy of something does not mean it means more in peoples lives, or that it holds more weight in influencing people when they witness it, especially when it comes to historical events. A more accurate image can be helpful, it can be used to intervene and help shape things, but it doesn't hold any secret power. That which is more creative and more engaging and which makes explicit attempts to bridge the historical or temporal divides, so works of fiction or art, novels, plays, video games, generally hold far more power. They have a much more potent effect on people and the way they view their past, and thus the way they take pieces of it to build the foundation of their present identities.

It is this dimension of the relationship to history, this gap between the impossibility of its representation and the ways in which more "creative" or less accurate interpretations or representations work to fill in the gaps, that is almost completely lost on Chamorros. If you think that my discussion so far is too abstract or just too crazy, you probably wouldn't think so if you have ever participated in any discussion with a group of Chamorros, on what artifacts or material and creative forms constitute things such as "Chamorro culture." It is an obvious truism that cultures are always constantly changing, and constantly berating themselves for those shifts. Things are lost, and sometimes the story of that loss is banal and boring, almost incidental, in other cases it is violent and tragic.

As a people who "lost" so much during Spanish colonization, and for whom knowledge of that period depends primarily on Spanish and European accounts of that era, Chamorros constantly struggle with what to do with the absences or violent gaps that they have inherited. Cultural forms such as dances and canoe navigation were forbidden and lost. We know that they were there, but the forms that they took when they were eradicated are unknown. So the question of debate in these discussions is always, well since they are gone, can Chamorros ever really have dances or culture like that again? What can we authentically do with that loss? Can we ever authentically overcome those tragedies?

As a people who "lost" so much during Spanish colonization, and for whom knowledge of that period depends primarily on Spanish and European accounts of that era, Chamorros constantly struggle with what to do with the absences or violent gaps that they have inherited. Cultural forms such as dances and canoe navigation were forbidden and lost. We know that they were there, but the forms that they took when they were eradicated are unknown. So the question of debate in these discussions is always, well since they are gone, can Chamorros ever really have dances or culture like that again? What can we authentically do with that loss? Can we ever authentically overcome those tragedies?

Your answers to these questions depend alot on not just your ideas of culture, but your opinions on history as well. For those who adhere to a very strict and unidimensional view of history, the answer is no, because its not accurate. We can't ever know what they were like, those pieces of culture were the authentic parts us and they are now gone, and no matter what we invent now as our culture, is will always be something we borrow, something which is never really ours. It is for this reason that discussions of the resurgence of Chamorro dance and culture are always accompanied by generally stupid and ignorant discussions on how these forms are inauthentic since they are just copying or borrowing from other cultures. The version of history that these island historians are clinging to is one of simplicity. History is a easy and obvious process, it moves in ways in which we can easily recognize things, and also seems to be a process in which things are neatly divided in such a way that you can always judge what is or isn't accurate.

The creative approach to history, is all based on those facts of history being diverse, flowing freely and in chaotic and contradictory ways, and is never completely knowable and is almost always an interpretive process which has nothing to do with the past, but always with the present. The creative approach happens within this universe of assumptions, it knows that history is not simply the easy answer to that axiom that "to know where we are going, we must know where we came from." It works, sometimes in more explicit ways other times in more implicit ways, on the assumption that the past and the future do not exist in separate tanks, and that history is not so much the abstraction of the past, but always how it relates and makes the present possible. Not just in a historical, timeline, series of events sense, but how it infuses in us today, how those events and the always changing meanings to that past literally pierce the present, making and unmaking it at every moment.

The creative approach to history, is all based on those facts of history being diverse, flowing freely and in chaotic and contradictory ways, and is never completely knowable and is almost always an interpretive process which has nothing to do with the past, but always with the present. The creative approach happens within this universe of assumptions, it knows that history is not simply the easy answer to that axiom that "to know where we are going, we must know where we came from." It works, sometimes in more explicit ways other times in more implicit ways, on the assumption that the past and the future do not exist in separate tanks, and that history is not so much the abstraction of the past, but always how it relates and makes the present possible. Not just in a historical, timeline, series of events sense, but how it infuses in us today, how those events and the always changing meanings to that past literally pierce the present, making and unmaking it at every moment.

Returning to the initial object of this post, the subject matter of the film Chi Bi, I only hope that someday soon, more Chamorros will weaken the historian's eye that they take to their history and to the long journey of our people. That they will let their history breathe. I don't say this because the telling and re-telling of our history should be a process of "anything goes" and that accuracy doesn't matter. But I only say this to remind us that accuracy isn't everything and doesn't actually solve anything. As I said earlier, there is no magic to accuracy, it doesn't magically affect the boundaries of our imaginations, it doesn't magically communicate lessons or unite people, it doesn't make them care about their history any more, or make them more prone to learn "accurate" lessons of it. My point is that being accurate is not enough. Often times the way we represent Guam and Chamorro history are pared down to only that which is "true" or only that which we can confirm is accurate, this leaves us with frankly no history, nothing to build upon, except massive holes and gaps in who we are and where we came from, the names of maga'lahi but no stories to accompany them, the images of events and no stories to support them. That is why, although the Hale'-ta series is very informative and brings together, the books often cover the exact same ground in the same way. Collections of Chamorro legends and traditional stories tell the same ones over and over.

It is actually a point of sadness and tragedy, when the history of a people can be so easily contained into a single book or a small series of books. It means that people mistake a timeline or summary of history, its distillation to its most accurate parts, for the spirit or the force of their history. To make that mistake means to make Chamorro and Guam history wastelands, to deprive them of any life of vitality, beyond what you can say was written down. Academia may work that way, but history and people don't. The result of this is that there is nothing really that ties us to our history, and then we wonder then why Chamorros are so invested in American dreams and Americanization. It provides a mythology, it provides a glorious history full of wonderful fictions. It is full of reasons to be proud of it or attached to it, figures who have less than accurate movies, books or plays about them, events which recount them in stunning ignorance of any historical detail or accuracy.

It is actually a point of sadness and tragedy, when the history of a people can be so easily contained into a single book or a small series of books. It means that people mistake a timeline or summary of history, its distillation to its most accurate parts, for the spirit or the force of their history. To make that mistake means to make Chamorro and Guam history wastelands, to deprive them of any life of vitality, beyond what you can say was written down. Academia may work that way, but history and people don't. The result of this is that there is nothing really that ties us to our history, and then we wonder then why Chamorros are so invested in American dreams and Americanization. It provides a mythology, it provides a glorious history full of wonderful fictions. It is full of reasons to be proud of it or attached to it, figures who have less than accurate movies, books or plays about them, events which recount them in stunning ignorance of any historical detail or accuracy.

This is especially so in the case of Chamorros, where what we accept as giving a history accuracy is half silence and the other half colonizer's words. To work with that oppressive historian's eye in this context, we condemn ourselves to those limits. To accept whatever explorers or priests chose to write down, to see ourselves and our imaginations as limited to them, to hinge our authenticity, which is in and of itself a horribly contradictory and impossible concept as reliant on whatever whatever they saw in Chamorros as worth writing down. Its a way of continuing our colonization, finding a way to shackle ourselves with more chains of the colonizer.

Comments