Protest Culture

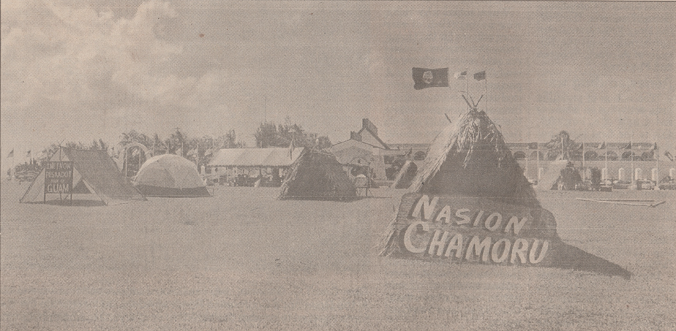

When the protest group Nasion Chamoru first emerged decades ago, it created a conflict in the minds of people on Guam. On the one hand you had a group of people who were an emphatically embodying “Chamoru” things.

They were speaking Chamoru, fighting for Chamoru lands and their return, protecting Chamoru rights, and even sometimes sported ancient Chamoru jewelry. But at the same time, for many people, the group seemed to be against everything Chamorus supposedly represented.

Chamorus are supposed to be respectful, gairespetu yan gaimamhlao, do not speak out and politely submit to any form of authority. In the way Nasion Chamoru did not shy away from open defiance and critique of the local and federal governments, they seemed so taimamahlao or tairespetu (without shame or respect).

Every culture has their conservative and progressive elements, and an ideological fight always takes place over what is considered to be acceptable and unacceptable. For some, openly fighting for their rights and for their culture can be considered to be a high ideal, a laudable action. In others, the same actions might be considered shameful and not in line with the spirit of the culture.

Your position in this debate depends on what your definition of a Chamoru is. For many people, a Chamoru is a very narrowly conceived ideological creature. It exists without what historians call “agency.” As one U.S. Naval governor put it before World War II, Chamorros are “poor, ignorant, very dirty in their habits, but gentle and [free] from ambition or the desire for change or progress.”

This Chamoru is a helplessly passive beast, it always waits to be liberated or for someone else to fix its problems. It is unfailingly hospitable to anyone who visits Guam and lives only to chillax and kick back.

This conception of Chamoru culture tells only part of the story. It gives you a view of only part of the history and part of the culture. Gi minagahet, if Chamorus and their culture were limited in this way, the history of this island would be very different. There would be no Chamoru language, the island would be almost entirely filled with military bases, and there is a chance there wouldn’t be an Organic Act either.

The

progressive aspects of Chamoru culture, symbolized by a willingness to

speak out and to challenge the way things are in order to improve them,

has always been there. It has always sustained Chamorus and encouraged

them, even when history seemed determined to destroy them by throwing

colonizer after colonizer at them for more than 300 years. For example,

protesting has been a significant part of Chamoru culture since 1898,

and in every era people have made a stand and spoken out against things

they saw as unjust or in need of change.

In 1901, Chamorus sent their first of many prewar petitions to Washington D.C. in an effort to obtain a civilian government for Guam and some basic rights and protections. The first petition had only 32 signatures; later petitions held thousands of signatures, but all were unsuccessful in moving the U.S. government to treat Chamorus with some basic dignity. During this same era, Chamorus in small numbers politely protested or lobbied against the policies of the U.S. Navy over things such as the deportation of Chamoru lepers, the public execution of criminals, and even a law that the U.S. Navy passed prohibiting intermarriage on Guam.

The most famous of these modern Chamoru protests is the Guam Congress Walkout, which was symbolically helpful in getting the Organic Act passed for Guam. The Guam Congress Walkout made headlines around the U.S. when Chamorus in the Guam Congress walked out of session, refusing to return until the U.S. provided them with some basic rights. This was a time when Chamorus were irritated at the way they were being treated by the U.S., after they had suffered under the Japanese for remaining loyal to them. As such, in the immediate postwar years, Chamorus organized many large and small protests. At least two strikes were organized by Chamorros over the issue of segregated working spaces. A protest was even held over the return of Navy Radioman George Tweed to the island. Tweed hid and evaded capture in Guam by the Japanese for 31 months with the help of Chamorus, but had made some disparaging remarks about the conduct of some Chamorus, most importantly Father Jesus Baza Duenas. The protest even featured signs, some of which an angry Tweed knocked to the ground and stomped on.

Protest is an integral part of all cultures, and it is a defining aspect

over whether a culture can adapt and persist, or whether it will

disappear.

Comments