Circumnavigations #9: The Death of Magellan

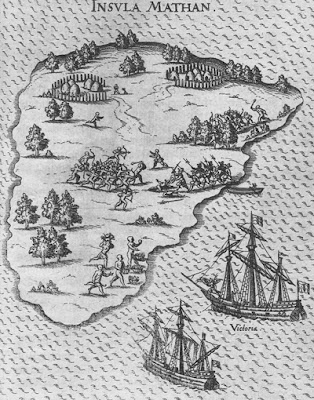

Below is an account of the death of Ferdinand Magellan, on the island of Mactan in 1521.

I've been reading different historians and their interpretation of the events and where they situate his death in the context of his personality and his behavior. At the conference that I was at in Madrid last month, there was quite a bit of myth-making around Magellan. Some of it is deserved, as he did guide a voyage that was into water unknown to Europeans. But the success of his mission has a tendency to lead historians to make generalizations of greatness.

Many historians take the flaws in Magellan's character and then argue that they were actually strengths because of the time that he lived in and because of the obstacles, both geographic and human that he faced. For example, Magellan's tactics in dealing with the concerns or the fears of his men, is argued to be a strength since he was dealing with medieval and pre-modern superstitions about the world that he refused to let ruin his mission. While we can give Magellan some credit, we shouldn't imagine him to be the spear of enlightenment, or like the Immanuel Kant of the sea.

This is a tic that historians have long struggled with and continue to contend with today. This notion that if something happened, then it was supposed to happen, and most factors involved, contributed to and must have aligned in a variety of ways to make it possible. This sounds very reasonable, but the problem though is that it can infuse a sense of destiny into history, that when it is written, that which contributed to an emergence and that which did not, are both tied together by a similar logic.

So even Magellan's flaws, some of which made his voyage more difficult and dangerous, become in a historian's review things that made him that much greater and that much more heroic, and then actually became things that helped in some indirect way, contribute to his success. At the conference in Valladolid last month, there was one presentation that looked into this argument, and it was a rare one. The scholar noted that in the period of Magellan, he wouldn't have been considered to be a "good" captain because of his lack of rapport with his sailors and his unwillingness to hear them or listen to them. The scholar noted that this was a key skill for captains since the men weren't paid that great and weren't in the military and national identities as we known them today didn't really exist. This meant that a good captain had to be a good listener, not a loud and brash tyrant of the sea. A good captain for the time worked with his men to ease their fears and take advantage of their knowledge, and also find a way to still respect them, even while dismissing various superstitions that they held about sea monsters. Magellan did not have these skills and that is why the first phase of his journey was filled with talk of mutiny and actually mutiny.

The death of Magellan is another such moment, where historians struggle with how to situate it. One of the most fascinating things about reading history of this sort, is that there are only a limited number of accounts. Some people are discovering more possible accounts hidden in dusty archives, but a thousand scholars are basically dealing with the same handful of pages about what happened. It is interesting to see the shades of truth and destiny they bring to bear in order to differentiate their telling, their interpretation from another.

*********************

In the afternoon the Christian king sent a message with our consent to the people of Matan, to the effect that if they would give us the captain and the other men who had been killed, we would give them as much merchandise as they wished. They answered that they would not give up such a man, as we imagined [they would do], and that they would not give him for all the riches in the world, but that they intended to keep him as a memorial."

-->

-->

I've been reading different historians and their interpretation of the events and where they situate his death in the context of his personality and his behavior. At the conference that I was at in Madrid last month, there was quite a bit of myth-making around Magellan. Some of it is deserved, as he did guide a voyage that was into water unknown to Europeans. But the success of his mission has a tendency to lead historians to make generalizations of greatness.

Many historians take the flaws in Magellan's character and then argue that they were actually strengths because of the time that he lived in and because of the obstacles, both geographic and human that he faced. For example, Magellan's tactics in dealing with the concerns or the fears of his men, is argued to be a strength since he was dealing with medieval and pre-modern superstitions about the world that he refused to let ruin his mission. While we can give Magellan some credit, we shouldn't imagine him to be the spear of enlightenment, or like the Immanuel Kant of the sea.

This is a tic that historians have long struggled with and continue to contend with today. This notion that if something happened, then it was supposed to happen, and most factors involved, contributed to and must have aligned in a variety of ways to make it possible. This sounds very reasonable, but the problem though is that it can infuse a sense of destiny into history, that when it is written, that which contributed to an emergence and that which did not, are both tied together by a similar logic.

So even Magellan's flaws, some of which made his voyage more difficult and dangerous, become in a historian's review things that made him that much greater and that much more heroic, and then actually became things that helped in some indirect way, contribute to his success. At the conference in Valladolid last month, there was one presentation that looked into this argument, and it was a rare one. The scholar noted that in the period of Magellan, he wouldn't have been considered to be a "good" captain because of his lack of rapport with his sailors and his unwillingness to hear them or listen to them. The scholar noted that this was a key skill for captains since the men weren't paid that great and weren't in the military and national identities as we known them today didn't really exist. This meant that a good captain had to be a good listener, not a loud and brash tyrant of the sea. A good captain for the time worked with his men to ease their fears and take advantage of their knowledge, and also find a way to still respect them, even while dismissing various superstitions that they held about sea monsters. Magellan did not have these skills and that is why the first phase of his journey was filled with talk of mutiny and actually mutiny.

The death of Magellan is another such moment, where historians struggle with how to situate it. One of the most fascinating things about reading history of this sort, is that there are only a limited number of accounts. Some people are discovering more possible accounts hidden in dusty archives, but a thousand scholars are basically dealing with the same handful of pages about what happened. It is interesting to see the shades of truth and destiny they bring to bear in order to differentiate their telling, their interpretation from another.

*********************

"On Friday, April twenty-six, Zula, a chief of the

island of Matan, sent one of his sons to present two goats to the

captain-general, and to say that he would send him all that he had promised,

but that he had not been able to send it to him because of the other chief

Cilapulapu, who refused to obey the king of Spagnia. He requested the captain

to send him only one boatload of men on the next night, so that they might help

him and fight against the other chief. The captain-general decided to go

thither with three boatloads. We begged him repeatedly not to go, but he, like

a good shepherd, refused to abandon his flock. At midnight, sixty men of us set

out armed with corselets and helmets, together with the Christian king, the

prince, some of the chief men, and twenty or thirty balanguais.

We reached Matan three hours before dawn. The captain did not wish to fight then, but sent a message to the natives by the Moro to the effect that if they would obey the king of Spagnia, recognize the Christian king as their sovereign, and pay us our tribute, he would be their friend; but that if they wished otherwise, they should wait to see how our lances wounded. They replied that if we had lances they had lances of bamboo and stakes hardened with fire. [They asked us] not to proceed to attack them at once, but to wait until morning, so that they might have more men. They said that in order to induce us to go in search of them; for they had dug certain pitholes between the houses in order that we might fall into them.

We reached Matan three hours before dawn. The captain did not wish to fight then, but sent a message to the natives by the Moro to the effect that if they would obey the king of Spagnia, recognize the Christian king as their sovereign, and pay us our tribute, he would be their friend; but that if they wished otherwise, they should wait to see how our lances wounded. They replied that if we had lances they had lances of bamboo and stakes hardened with fire. [They asked us] not to proceed to attack them at once, but to wait until morning, so that they might have more men. They said that in order to induce us to go in search of them; for they had dug certain pitholes between the houses in order that we might fall into them.

When morning came forty-nine of us leaped into the water up

to our thighs, and walked through water for more than two crossbow flights

before we could reach the shore. The boats could not approach nearer because of

certain rocks in the water. The other eleven men remained behind to guard the

boats. When we reached land, those men had formed in three divisions to the

number of more than one thousand five hundred persons. When they saw us, they

charged down upon us with exceeding loud cries, two divisions on our flanks and

the other on our front. When the captain saw that, he formed us into two

divisions, and thus did we begin to fight. The musketeers and crossbowmen shot

from a distance for about a halfhour, but uselessly; for the shots only passed

through the shields which were made of thin wood and the arms [of the bearers].

The captain cried to them, " Cease firing! cease firing I " but his

order was not at all heeded. When the natives saw that we were shooting our muskets

to no purpose, crying out they determined to stand firm, but they redoubled

their shouts. When our muskets were discharged, the natives would never stand

still, but leaped hither and thither, covering themselves with their shields.

They shot so many arrows at us and hurled so many bamboo spears (some of them

tipped with iron) at the captain-general, besides pointed stakes hardened with

fire, stones, and mud, that we could scarcely defend ourselves. Seeing that,

the captain-general sent some men to burn their houses in order to terrify

them.

When they saw their houses burning, they were roused to

greater fury. Two of our men were killed near the houses, while we burned

twenty or thirty houses. So many of them charged down upon us that they shot

the captain through the right leg with a poisoned arrow. On that account, he

ordered us to retire slowly, but the men took to flight, except six or eight of

us who remained with the captain. The natives shot only at our legs, for the

latter were bare; and so many were the spears and stones that they hurled at

us, that we could offer no resistance. The mortars in the boats could not aid

us as they were too far away. So we continued to retire for more than a good

crossbow flight from the shore always fighting up to our knees in the water.

The natives continued to pursue us, and picking up the same spear four or six

times, hurled it at us again and again. Recognizing the captain, so many turned

upon him that they knocked his helmet off his head twice, but he always stood

firmly like a good knight, together with some others. Thus did we fight for

more than one hour, refusing to retire farther.

An Indian hurled a bamboo spear into the captain's face, but

the latter immediately killed him with his lance, which he left in the Indian's

body. Then, trying to lay hand on sword, he could draw it out but halfway,

because he had been wounded in the arm with a bamboo spear. When the natives

saw that, they all hurled themselves upon him. One of them wounded him on the

left leg with a large cutlass, which resembles a scimitar, only being larger.

That caused the captain to fall face downward, when immediately they rushed

upon him with iron and bamboo spears and with their cutlasses, until they

killed our mirror, our light, our comfort, and our true guide. When they

wounded him, he turned back many times to see whether we were all in the boats.

Thereupon, beholding him dead, we, wounded, retreated, as best we could, to the

boats, which were already pulling off.

The Christian king would have aided us, but the captain

charged him before we landed, not to leave his balanghai, but to stay to see

how we fought. When the king learned that the captain was dead, he wept. Had it

not been for that unfortunate captain, not a single one of us would have been

saved in the boats, for while he was fighting the others retired to the boats.

I hope through [the efforts of] your most illustrious Lordship that the fame of

so noble a captain will not become effaced in our times. Among the other virtues

which he possessed, he was more constant than ever any one else in the greatest

of adversity. He endured hunger better than all the others, and more accurately

than any man in the world did he understand sea charts and navigation. And that

this was the truth was seen openly, for no other had had so much natural talent

nor the boldness to learn how to circumnavigate the world, as he had almost

done. That battle was fought on Saturday, April twenty-seven, 1521.

The captain desired to fight on Saturday, because it was the

day especially holy to him. Eight of our men were killed with him in that

battle, and four Indians, who had become Christians and who had come afterward

to aid usi were killed by the mortars of the boats. Of the enemy, only fifteen

were killed, while many of us were wounded.

In the afternoon the Christian king sent a message with our consent to the people of Matan, to the effect that if they would give us the captain and the other men who had been killed, we would give them as much merchandise as they wished. They answered that they would not give up such a man, as we imagined [they would do], and that they would not give him for all the riches in the world, but that they intended to keep him as a memorial."

-->

Comments